After the tires stop screeching she heard what she was sure was splatter. She left mother’s soup on the stove and went to the window and then to the door and then she was quickly across the front yard to the edge of the lawn. The sun was fiery and luminous and a small plane arched just beneath the sun. The white-tails were everywhere, fearless and dumb, the young out to stretch their legs and eat ravenously, the elders ahead of them, spiriting instructions. In the middle of the night they ate her hydrangeas and her roses, leaving a few tattered leaves for the next time. There wasn’t a stop sign for a mile in either direction, only a couple of yellow ones that said Deer Xing and another hand-made that said Save the Turtles.

It was sleek, expensive, funereal black with rear fins like vampire fangs. The driver was out, squatting by the passenger-side wheel-well, a male, maybe thirty, with a Fu Man Chu. She knew her way around cars thanks to Tobias and this one was a show-stopper. There was something just plain evil about it. “Okay?” she said. Her back was to the sun and the glare flamed off his sunglasses. He got down on one knee. “A turkey is it?” she said. She hadn’t seen before someone stop and practically mourn Christian-like on behalf of a flattened squirrel.

“It’s a cat,” the driver said. “Is it yours, Ma’am, is it yours? Good grief. I’m sorry. It froze right up like a … golly-Jesus. I didn’t have time to stop. That car it just mauls the road. I also want to make you aware that I am completely sober.”

“Is it a calico?”

“From the looks of the tail here, it’s got some orange in it. That’s it, right? It’s yours? I’m dumbfounded,” he said. “I might as well just give up.” He had an earnest farm-boy twang, something you assumed you only heard on TV. You’d never believe people spoke that way, smashing syllables to death and then dragging them away, but this one did. He got to his feet and he was tall and brown in the sun and there was a slice of fresh tire grease on his pale yellow shirt. This took place in his mustache period, but to her it just made his soft, broad face flatter, his complexion somehow more burnt and Indian-like. He was overall pleasant-looking, though, and had the whitest teeth she’d ever seen on a man not selling toothpaste. It was the voice she was somehow familiar with, but she didn’t know any man who drove a car like that, or for that matter said things like golly-Jesus.

“You killed Fat-ass,” she said, noticing the girl in the passenger seat for the first time and how skinny she was. She wore a bikini-top and there was no telling what else. It was obvious she had no interest in making eye contact since the window was rolled all the way up and her sunglasses must have blocked a good degree of her peripheral vision. The driver, meanwhile, was talking to himself. If she didn’t know better, it looked like he was prayer-panicking. Annie took a step closer, thinking to herself how silly, how ordinary, people must do this to him all the time, but she couldn’t stop looking and leaned in for a closer look. He must have been an actor, or a singer. He smiled like he wanted to put an arm around Annie and tell her everything was going to be alright, or maybe it was like someone recognizing a bloody sharp piece of irony. He wasn’t out joyriding in a car like that hunting for cats to flatten, she was sure. Either way he’d been drinking heavily, that much she was sure of, too, being the wife of a mechanic. “Then you’re okay? You’re not shaken, are you?”

“I’m not hurt,” he said. “It didn’t feel like much. It’s such a heavy thing. But stomping on the brakes gave us a pretty good jolt.”

And then, simply because she knew if she reported the incident–accident?–the police would quickly surmise this man, whomever he was, was driving while intoxicated, and because she assumed he did not want that to happen, she took a liberty. “You live here on Shelter Island?” She immediately regretted it. He was probably already thinking poorly of her, thinking her some flunky local, but none of that was true. Her mother had been born in that house behind her. She had been born in that house. That house had sheltered several generations of respectable Fowlers dead and buried not a couple hundred feet from where she was standing. She was practically local royalty.

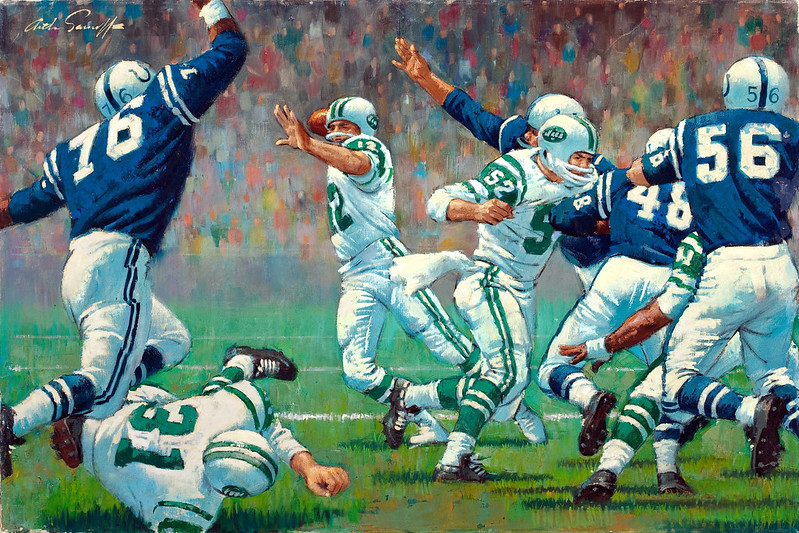

But why would she report anything to the police? He’d done nothing wrong. As if to prove it, he took off his sunglasses. “I’m from a little town in the state of Pennsylvania, ma’am. I live in Manhattan now. That’s Paulina, in the car. Hey, Paulina, can you roll down the window? Say Hi here to Miss? That’s a fine name, Miss Fowler. Thank you. I don’t know why she can’t open the window, we’re not hiding anything. Stay in the car and don’t touch nothing. You know Super Bowl III? Well, a couple years back, I won that and got a little more famous than I already was, but maybe yours is not a football household. And you know what I say? Bless your heart if football’s the first thing on earth you could live without. It annoys the you know what out of me and it’s the farthest thing from my mind. Football, I’m saying. Especially now. That poor old pussy.”

“Vacationing then?” Annie Fowler said.

“Tell me, ma’am, because it’s important. Was that your cat? Gol-ly, I’m just on my way to a friend’s pad. Howard is his name, do you know him? Howard Manault? No, well, this is a small community it seems and we really dig it here. It’s real remote, and the ferry is just like something from the old whaling days, isn’t it? Look, just so we’re clear, I couldn’t not hit him, your cat, no way. Or her, is it? Look, I would have went square into that big tree, I could have died.” He looked down at the orange fur smeared into the asphalt. “It’s always something,” he said. Although she took no notice, he waved to the girl in the car like he was going to walk away and leave her there. Then he said out loud, as though he were alone, “You should have just kept going, no one would had known the better. But of course you stop.”

Annie thought he was rather lucky that it was just Fat-ass and not a six-point buck. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been so close to such an expensive-looking car.

“I suppose I know you from somewhere,” she said.

“Joe Namath,” he said, and the space between them shrunk and shadowed as he stuck out his hand and smiled like he hadn’t said his own name in a while and it pleased him to hear it, the earthliness of it. It again looked like he would have preferred a hug.

“Beauty Mist Pantyhose. I knew I knew you. And my, you won the super bowl, too? Tobias used to talk about football. He did talk endlessly about the most boring subjects. You’re the one with the pretty man legs.”

“Gams from God,” he said, holding a leg up in the air and finishing with a small judo kick. His bellbottoms, she remembered, shook violently, and he smiled but quickly sobered at the reference to God, or she thought so anyway.

“I think I had a pair once,” she said. “They weren’t my brand but I had a pair.”

“Poor little kittie,” he said.

“Imagine what they’ll do for yours,” she said, expecting that maybe he’d recite the beginning lines of the commercial, since that was how it ended, but life was more interesting down near the tire.

“Don’t beat yourself up over Fat-ass, I wasn’t attached to him.”

“You weren’t?” he said.

“It wasn’t a good life,” she said, and went into detail about Fat-ass’s many untreated ailments. The cat had been hanging around since before Tobias died, snuggling with her tomatoes and letting flies party on his face. Tobias had been the one to embrace the cat, and now she kept it around so that she wouldn’t forget him. “It was always drooling. That ugly little mouth glistened in the dead of winter,” she said.

“Hey, now you might not feel sorry about it, but I do. You don’t have to be a relation to something to love it just the same. Just try to have a little respect. Try to dig a little compassion.”

“You did him a favor,” she said. “Nobody loved that cat.”

“You’re making me feel terrible about it,” Joe Namath said. “More terrible than I already do.”

“Well, you have no real authority to feel that terrible about who’s loved and who’s not. The world does not revolve around you, I’m afraid, whether you won the Super Bowl or the lotto or the contest for the world’s most average potato.”

“Now, hey,” he said. “Who said it did? Not me. All’s I’m saying is that I was responsible for ending this cat’s life, whether it was diseased and unloved or living groovy, and that’s all the ifs and buts. It’s just about respect for another living thing.”

“Are you a religious person?”

“I’m nothing,” he said, and then he spread his arms and moved his lips but it didn’t sound like anything but mumbling. In the place where the cat’s body and the road were now one, he began to weep. That’s when the passenger door swung open and long legs and short shorts wobbled out like one of the young deer stretching her legs and vomited right there, pretty much right on top of Fat-ass’s mangled body.

But Joe Namath was not paying attention and he sat down against the tire. The girl went back into the car and turned on the radio.

“All I do is leave food and water out,” Annie said. “He comes and goes and his day was coming any day now, and if it wasn’t you it would have been drunk Tiller boys racing their idiotic trucks.”

“Nevertheless, I’m bummed about it,” said Joe. “The whole thing. I’m not here to fight the world, or kill people’s cats—I just want to be Joe from Beaver Falls and do right by me and the people who look up to me. I don’t interfere with other people’s affairs and I don’t want people to interfere with mine. That’s how I operate. Simple, you dig? I’m a straight-up guy operating on simple principles, try not to hurt things, try not to make things worse. Yeah, occasionally, a teenage girl gets all flustered because I didn’t sign her shirt, but the crowds get so big and I’m half claustrophobic. I can’t sign everything. Think about it like this: What’s the opposite? I can sign everything. That doesn’t work, either.”

“You want the middle ground,” she said.

“That’s right,” he said. “I want good-looking views on both sides.”

“You didn’t know that cat or love it or care for its health. It would have died a violent death by someone else’s hands and you would have been drinking champagne at your party. You’re sad for yourself, Joe, and how can you be?”

“Listen,” he said, standing and dusting off his pants. His hair was thick and still nearly perfect and there was some vomit on the leg of his jeans. “I’d feel a lot better if I could do something for you, for your trouble? Sign something for you, or give you something, for the trouble? Tickets maybe?”

“No, no,” she said. Just in case, she’d already memorized the license plate. Would he trust her enough to drive away, leaving the scene of the incident, or accident? That would make it worse. “What you have to be sad about it,” Annie said.

“There’s that hill,” he said, looking down the road from where he came, again like he was talking to himself, “and I thought of course it’s going to turn back, or just hit the afterburners. It made a terrible sound.”

“I’m sure it did and with any luck it will haunt you forever.”

“Listen, can I sign you an autograph? It would be my privilege. You gotta ball or something? Your husband, or one of the grandkids.”

“You want to sign something so bad, you should go down to the Legion Hall at the circle just about a mile from here. The boys in there appreciate nice automobiles.”

That’s when Mother pushed the screen to the sunporch open with the tennis ball at the end of her cane, and she called out, “Yoo-hoo, Annie? I can’t see you there’s too much sun. Who’s that with you?”

“Joe Namath,” she called back. “The football player.”

“Yoo-hoo, Annie, yoo-hoo. You left something on the stove. It’s smoking.”

“The soup!” she said, and then she left Joe Namath and his evil car and his girlfriend and the smeared cat on the side of the road to try and save mother’s lunch before it burnt. When she’d turned off the stove and gone back to the porch, they were gone.