She never pitched my shit out a window—clothes, laptop, record player—like breakups on TV. My wife. My ex. My tall, lanky, Janice. She didn’t even yell at our end. She simply chose God over me, said she felt called to a life of poverty and service. She told me all of this on a Tuesday night, after driving home from the construction site, then pulled me in the bedroom and gave me every bit of her for the last time. Afterward, as we stared up at the hairline crack in our plaster ceiling, she asked for our savings, for me to file the paperwork she’d signed and dated, and to drop her and her backpack off at the airport in the morning, to catch a nonstop to missionary school.

It’s hard to blame God because I can’t see or shake him. He seemed physical and present when Janice talked about him. I should’ve been more concerned. I should’ve stepped in after the evangelical solicitors knocked on our door. There’d been a pit inside her that our marriage and careers and house couldn’t fill. Kids or pets might’ve done the trick, but she’d been given faulty female parts and terrible allergies. I should’ve taken time to snap signs together, like puzzle pieces, to get a clearer picture of where she was moving. She’d slowly dwindled down her wardrobe until the walls and cedar planks of her closet took on more space than her clothes. She’d turned down good promotions at the hospital, to keep her time and energy for bible studies and volunteering in shelters.

I thought her faith was beautiful and simple, free from all the pressures I’d known growing up Mormon. But I still wouldn’t go to church with her. She never even asked. I’d sworn off all religions in high school, then left home for Boise State, not Brigham-Young, like my seven older brothers and sisters. That’s where we met, in an introduction to something class, and we decided to drop anchors in Boise after graduating and finding jobs and getting hitched, almost five years ago. They weren’t bad years, either. When you thumb through our pictures on Instagram, it’s easy to think they were the best years of our lives. We went out on dates. We laughed all the time. And we swallowed up Stephen King books, as well as the Hollywood adaptions (she favored his supernatural stories over the horror, go figure). I never bitched about the way she spent her time. I learned to fill bible study nights and Sundays working in the garage, dovetailing jewelry boxes and mitering picture frames—the same ones I’d first made for Janice—for my Etsy store.

Our house sold in a weekend, her Subaru wagon in a week. I tried to hang on to them for a time, along with my project-manager job, but they became hollow shells, like the pit in Janice’s stomach. I’ve read Boise’s the fastest growing city in America right now, yet Janice and I left for the hills. Janice, for a mice-infested straw hut in Ecuador (that’s where the postcards come from, two or three a month). Me, for the Sawtooth Mountains, where Janice loved to camp and hike, where I found five acres for sale. So far I’ve paid a man to drill a well, then dug a hole in the earth myself for a septic tank. Next month linemen will branch off the power pole at the highway, then peg up the hillside, to my still-curing 15’ by 15’ cement form.

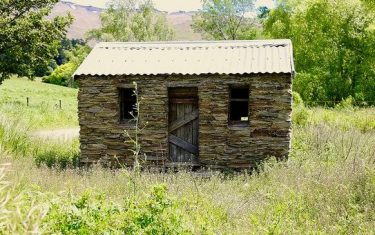

It’s a lot like camping right now. I’m still months out from finishing my 225 square foot cube, with walls as tall as they are wide and a roofline that mimics the slope of the hillside, but the skeleton is quickly taking shape. I drive my truck and trailer down to the valley in the mornings, to work my new finish carpentry gig in the glitzy mansions of Ketchum and Sun Valley, then haul wood scraps home each evening, where I hammer and saw by hand until dark. I’ll need to have it finished before the frost in September, but that’s several months away, and I’m not worried. The loneliness is the only thing that worries me. That, and the fact that I’ve started talking to myself.

The woman at the humane society says hypoallergenic dogs, like Shih Tzu’s and Poodles, wouldn’t do well living in the snow half the year. She asks if I’d like to meet Patty, a Saint Bernard, then takes me to her kennel, where Patty walks right up to my hand and slobbers all over it. It’s hard not to love her, even though she’s older and smells bad. The woman tells me that she’s been stuck in a kennel for five weeks, because no one wants to rescue an older dog. Which is all the guilt trip I need to sign a bunch of papers and pay for Patty’s boarding, then lead her to the cab of my truck, where she hikes inside.

Janice’s postcards are short and to the point, but constant. She talks about her hut and garden patch, how she’s learning to speak Quichua and use her medical background to doctor the native people, if they get sick enough to trust her. I haven’t chicken-scratched a letter on notebook paper since I picked up Patty at the shelter, weeks ago. There’s too much to say. But I’ll take time to write this Thursday—summer solstice—the longest day of the year. I’ll tell her I’ve learned to speak dog language. I’ll tell her how Patty goes everywhere with me, to jobsites and restaurant patios in Ketchum after work. I’ll tell her the metal roof is up, that the windows are hung, and the meter-main’s flywheel is turning. I’ll tell her this is the last letter I’ll write to Ecuador, the last time I’ll ask her to trade her hut for my cube, one tiny house for the other.