The Sweetest Scent

My father died of heart failure the same Chinese New Year girls began to draw my eye instead of ire. I wasn’t present for his death but figured it even since he wasn’t present for my life.

We all lived in Kowloon, but we no longer lived together, though mom claimed that the case even when we did. When he roamed within the same walls instead of a few kilometers away, he worked for people who only spoke to him in snaps. One snap for tea. Three to open the door, five to get out and close it behind him. He never looked at his superiors because his eyes were always closed as he smiled and bowed until they passed. They never looked at him because they were superior.

He smiled so much at work his face molded into a frown at home. He never talked to us when he spoke aloud, and never spoke aloud when he talked to us. Orders were given with grunts and snaps. If we ever caught his eye, we had gotten in his way.

Nights, he’d drink bottles of baijiu, then snap his fingers for his jacket. Slam furniture, slam doors as he left amidst my mother’s pleas to not. He’d return the next morning smelling nothing like her fragrance and carrying a bottle of Dynasty XO a few sips shy of dry. Mother would weep in pain, then rage as she’d scream that he’s nothing but a disgraceful eunuch. I always tried to look away before she hit the wall, and I always failed to plug my ears before she hit the tile. Then all was silence and sobs as we waited for his snore.

The end began with what I didn’t know was his way of bonding. Drunk, he told me the proudest moment of his life was as a boy he’d smelled Bruce Lee in person. He’d had the opportunity to shake his hand, but when the star approached, he could only smile and bow, his eyes clenched in what would be his greatest ability. “The scent of cologne was so strong,” he said, eyes closed to stanch the welling. “It was the smell of a great man.”

Then he left without a grunt or snap and never returned. It took forever to clear his stench from our home and hearts.

The last time I saw him alive was a Sunday morning Mom and I had yum tsa in Tsim Sha Tsui. Afterward, we walked the Avenue of Stars, and I saw him standing in the shadow of Bruce Lee’s statue. Staring out at the junks crossing Victoria Harbor, the South China Sea like dragon scales in the chop. I yelled his name several times, but he closed his eyes and lowered his head, then faced the statue and walked away.

Heart failure was listed as the COD my mother said, because “failure” was insufficient on a death certificate. At his wake, a family wearing white cried. Mom and I wore red and did not.

In Chinese tradition, if a son is not present at his father’s death, he must crawl toward the coffin wailing for penance. With Taoist chants around me, I lowered to palms and kneecaps and crawled toward the man who’d always ran away from me. Every millimeter neared left more of him behind. Clenching my eyes, I wept with laughter at the proudest moment of my life. The scent of formaldehyde was so strong. It was the smell of a failed man.

Lesson of Love

“What is to give light must endure burning.”

–Viktor Frankl

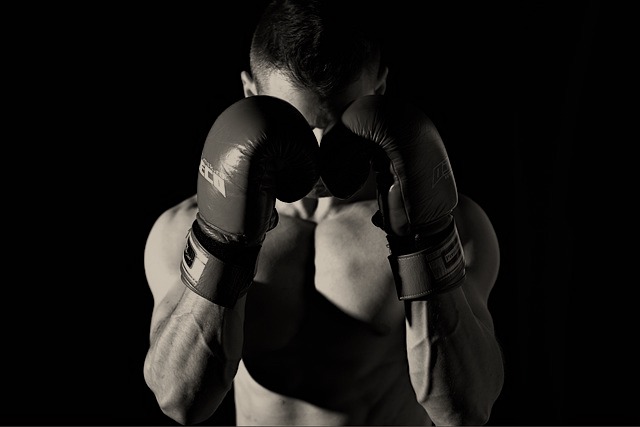

My daddy loved to box, and he loved to drink, but his true love was boxing while drinking. He hung an 80-lb. Everlast heavy bag in Mom’s parking space in the garage. A speed bag platform near the water heater closet. Anytime he was home, he’d take a bottle of popskull rye out, wrap his fists in tattered hand wraps, and bomb away until he and the booze were gone. The house shuddered under the machinegun bursts of leather on wood from the “crazy” bag. You’d hear each swat of knuckle on canvas as the punching bag lifted and dropped heavy on its chain. The rafters groaned and dust sifted down. Inside, dishes rattled in the cabinets, and pictures cocked on their nails or dropped altogether.

As the night wore on, Mom and I would jump whenever he began yelling at everyone in the garage even though he was alone. Then he’d come in glazed in sweat and smelling of wintergreen liniment. Knuckles bleeding through the wraps, he’d ramble on about his days as a member of “the fancy” when he was a middleweight in the Marine Corps. Eyes glossing with tears, he’d slur poetic about his amateur record of 48-3-1 before he lost a leg from the shin down in Fallujah.

When he got beyond smashed, he’d often take a punch-drunk fighter’s stance, and that meant to stop playing or eating or homework and meet him in his imaginary ring. He’d bob and weave, hooking a palm to my ribs. Feint and jab, smacking me across the cheek. Once I won by knockout though I never threw a punch. He just stumbled, fell, and began to snore. Most times it ended with me slumped fetal in a corner, covering my head so he couldn’t find an opening to land a shot or see my tears. Then he’d get bored, shake his head. “Daughter’s turning into a goddamn pussy,” he’d tell mom, then limp wall-to-wall down the hall.

One night, I eased out to the shadows in the garage as he drove dents into the heavy bag. The smell of whiskey and resin, sweat and motor oil. On the wall behind him written in his blood: PAIN IS FOR NOW. PRIDE IS FOREVER.

He stopped. “What.”

With no voice I said: “Would you teach me?”

He grabbed his bottle and bubbled it. “You,” he said, staring me down as if trying to mold me into someone else. Someone worthy. “You willing to die?”

I didn’t understand the question, let alone how to answer.

He snorted derision. “What makes a fighter’s not his will to live,” he said. “It’s if he’s willing to die.” He took a long snap off the bottle. “You willing to do that?”

I hooked a curl behind my ear. “How do I know?”

He looked past my head, through the wall in place and time. “Guy named Ronnie Jenkins showed me,” he said. “Called him ‘Rabbit Punch’ Ronnie cause he always threw rabbit punches.”

I tried to hide the dumb in my brain but the dumb on my face betrayed me.

“It’s where an opponent hits the back of the head in a clench,” he said. “Medulla oblongata.” He reached and pressed the base of my skull, almost tipping me headlong. “Where important motoric and brain functions cluster.” He smiled. “They’re illegal cause it’s a dangerous way to get put to sleep.”

“He did that to you?”

His smile widened. “I drop him twice the first two rounds, he catches me with a solid rabbit punch in the third,” he said. “Time the smelling salts woke me up, folks were already heading to chow.” He hooked a heavy shot into the bag. “Caught up with him down the road, though.”

“You get him good?” I said with too much excitement.

“Nope,” he said, shooting me a stink eye of disappointment. “I wanted to learn how to die so I asked him to do it again.” He slid his eyes from me back to the fancy, a kid and a leg ago. “That’s how you know.” He blinked back, telling me fighters have to step beyond the edge. Be willing to drink palmfuls of Hades. “You heard me right,” he said, finishing his bottle. “Palmfuls.” He lowered to my eyes. “So again,” he said. “You willing?”

I nodded.

He repeated the question louder.

“Yes sir!”

He nodded and unraveled his hand wraps. Began winding them through my fingers in a figure eight.

My arms were limp strings, my insides helium balloons. “What’d it feel like?” I asked, then wished I hadn’t.

“What’d what feel like?”

“Learning to die by getting knocked out.”

My daddy smiled and knuckled a bloody streak down my cheek, and I’ve never loved him more. He looked proud that I was his protégé, his fighter. His daughter.

“Lower your head,” he said. “I’ll show you.”

Taking a Bullet

I remember the day of the school shooting because I was not there. Well, I was, but when the gunfire erupted during morning recess from the woods near the playground, I was in the counselor’s office for my daily session to deal with my mom’s recent suicide.

I liked the counselor, and I liked her office. I’d sit on a worn couch holding a plush bear big as me or bigger while the counselor inquired about my dad’s lingering resentment. I called him Mr. Grumpy because he was always frowning. The bear, not my dad, though thinking back the name fit him too. I’d stare at my reflection in the bear’s marble eyes with the therapist asking if I believe her death was my fault. My reflection sometimes nodded. Other times it shrugged.

But that day, I was plugging the stuffing back inside the holes riddling Mr. Grumpy’s fur while telling her how dad and I had gone around the house collecting everything she’d left behind. From all her belongings to the stray black hairs in the couch cushions. Her pictures to errant fingernail parings still chipped with cherry red polish. We vacuumed, dusted, swept, and mopped up her shed dead skin, then opened every window to air out her scent. Everything gathered was burned in a firepit. We sold her car.

That’s when the counselor jumped and sat straight in her chair at the faint shots popping like firecrackers. Then the piercing screams. Then the sirens.

That night at home the rumors poured in, first in totals: how many dead, the number wounded. Then came the names of the victims and perpetrators. And it hit me those names were people, and those people were my teachers and classmates. Some of them friends, both shot and shooting. Before my mom and the counseling sessions, I was on that playground with them at recess.

Eating SpaghettiOs at the dinner table, I said, “Daddy?”

“Sweetheart.”

“If I was outside today, would I have got shot too?”

He drained his whiskey to the ice. “I don’t know,” he said. “Either way you dodged a bullet.” His raw eyes washed out with drink and pain, he said, “But we’re all of us dodging them every day, they’re just invisible.”

“Invisible?”

He poured another drink. “They zip right by our heads day and night,” he said. “We never know they’re there.”

I tried to see this in my mind. “Who’s shooting at us?” I asked, and he told me God.

“One day you turn here and live, somebody else turns there, and.” He downed the drink in a single breath. “They’re grub for grubworms.” He stood and walked to the sink. “Same store you shopped Monday night gets leveled by a tornado Tuesday morning,” he said, staring out the window wreathed in a hemlock of frost. “A person gets shot, surgeon tells them another quarter-inch to the right or left they’d be goners.” Scattered snowflakes began to appear from the black, melting on his silhouette reflected in the pebble grain glass. “Any given second,” he said, “we’re all just a quarter-inch away from tragedy.”

By the voice I’d come to know by heart, I knew he was crying. But I just smiled and ate my supper, thinking maybe what mom did wasn’t because of me, it was for me. That it was all on purpose, so I’d have to see the counselor and hug Mr. Grumpy at that time, on that day. Maybe she shoved me out of the line of fire and took the bullet instead. Ended her to continue me, dodging another day the unseen shots zipping by, popping invisible divots in the ground around me.

It took time after the massacre, but the school began to heal. So did I, though Dad was not so lucky. He’d been gut-shot by what I didn’t know was an invisible stray the night he found her, and whiskey took him a few years later. In the hospital, I held his purple hand as he twitched and bled out from the wound. “Bright side is, I finally got some of the cover at night,” he whispered, and closed his eyes. Another casualty of war on survival.