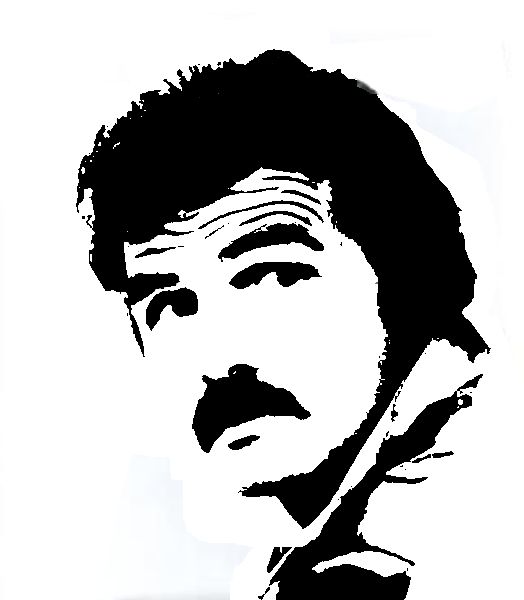

To get chicks you had to be like Burt. It was either be like Burt and get all the chicks or not be like Burt and get nothing. Since I didn’t have chicks I must not be like Burt.

So I studied Burt.

Burt was a football legend. Everybody knew that. He played one in movies and he was one in real life—Florida State. I’d seen pictures of him. His number, twenty-two. My number? Twenty-two. I was going to be like Burt and get all the girls. Why not? Who better than me to be like Burt? Who better than me to be a football legend and get all the girls? My dad, he was a football legend, or so my mom said.

“Why, he could have gone pro,” she’d told me on more than one occasion.

“So why didn’t he?

“Because he busted up his knee.”

“Dad, is that true?”

“No, I was too small.”

My Dad was humble, unlike Burt. Burt was cocky. He made you laugh while he kicked you in the balls and slapped you around. My dad wouldn’t kick you in the balls. I wondered if he even had it in him. It worried me sometimes. I didn’t like to think about it. Since I didn’t like to think about it I thought about it often. Like when we went to a ball game together. Instead of watching the action on the field I’d look around at all the drunken loud mouths in the crowd and ask myself if my dad would be able to hold his own if one of them came stumbling over and started up with him for no good reason. Chances were he’d try and talk sense into the moron. Tell them how childish fighting was. Then the no good drunk would beat him to a pulp right in front me. I hated thinking about it.

I’d gotten my coach to give me jersey number twenty-two. But I needed something else—playing time. “Patrino,” my coach hollered one day at practice. “You’re as slow as death.”

“That ball was over-thrown,” I said. “I couldn’t—”

“You know who would have caught it?”

“Who?”

“Burt.”

My coach wanted to be like Burt too. He’d stand on the practice field in a cowboy hat and twirl his thick mustache and make wise cracks at our expense all day long. Then when practice was over he’d jump in his black Trans Am and roar off through the parking lot with Daren Rodgers mom by his side. Daren was our tight end. His mom had huge breasts and a big blonde hairdo atop her head. A real Dolly Parton type. The kind of chick Burt Reynolds would fall for. Daren had been seeing a lot of playing time lately.

I needed playing time. I didn’t have to do anything once I got out there. I just had to be out there, beneath those lights. No chick wanted to be with a guy who stood on the sidelines the whole god damn game long.

I wasn’t about to offer up my mom though. Not that coach would want her. She had big round breasts but they weren’t the kind that Dolly Parton had. My mom’s boobs were the kind a short chunky Italian woman who spent her days wearing yellow rubber gloves up to her elbows while schlepping around a plastic bucket had. You know the kind.

There was only one way I was going to get into the game. I had to run faster. Is it possible to run faster than your legs can actually carry you? I mean, I knew it was possible to lift more weights. You just had to keep adding iron. The more iron you put on the bar the stronger you became. I’d done it myself. But how do you get your legs to move faster than they can already move?

My best pal Fred Ramirez said he’d help. Fred was fast. He was a long- haired Mexican who didn’t speak a lick of Spanish and wore red Vans and OP shorts and smoked a ton of weed. He was a natural athlete, lean and muscular, smoother than silk the way he carved his Logan Earth Ski across the school parking lot. He would have made a great wide receiver but he much preferred getting high after school as opposed to standing out in the one- hundred degree October heat in heavy football gear like the rest of us. This was good for me, seeing as I was a wide receiver.

Between training sessions with Fred I’d watch Deliverance. Even though there wasn’t a single chick in the movie, Burt was at his best. If one of the hillbillies who had come out of the woods had happened to be a woman instead of a homo she would have certainly fallen for him over the rest of those schleps he’d gone canoeing with. He kept saying all these cool, profound things about the end of civilization, while stringing up a cross bow and smoking a cigarillo. He had these thick, muscular arms—which I’d recently developed as well—and a skinny waist atop two not so long legs. I had a sneaking suspicion that he wasn’t all that fast either. I mean, I’d seen him run in The Longest Yard, and even though the scenes were in slow motion you could tell he was no Jesse Owens.

There was another reason coach kept me on the bench.

“Patrino! You are not a team player!” he yelled during film session. Then he stood up and pointed out how I had missed a key block. This was the one and only time I’d gotten into some real live action. “I give you one sticking opportunity and this is what you show me?”

“What’s that coach?”

“That you are not a team player.”

“Oh no?”

“You know what you are?” He switched off the film and turned on the lights. He wanted everybody to witness this. “What we have here,” he said. He had clearly seen every Paul Newman movie as well as every Burt Reynolds flick. “What we have here is… an individual.”

We all looked at each other, sitting there in our pads, one fat the other skinny, one dumb as hell, the other a slob, the other a freak. We were a rag tag bunch for sure.

“We can’t have any individuals on this here team,” he went on. “Individuals cost us games. Now turn them god damn lights back off!” He proceeded to rewind the film and show it again and again, my missed block. There I went, flopping all over myself upon the silver screen. Forward and back, over and over again, he clicked the clicker at the very spot I’d flung myself and whiffed. “Individual,” he kept repeating. “Only an individual could have missed a block like that.”

Fred stood some forty yards down the field with a stop watch in his hand. This was at the elementary school, when no one else was around. He’d told me to keep my head down and my knees up and my arms by my side. “Ready, set, go,” he hollered.

I ran as hard as I could.

“Five-five,” Fred said.

Coach was right. Death could come upon a fella in much less time than that.

“You’re too stiff,” said Fred. “You need to loosen up.”

I knew what that meant. He wanted me to stop this nonsense and go and smoke a joint with him. He wanted us to sit in the shade beneath the cafeteria awning and cool our minds and body off. What would Burt do? I wondered. I considered the type of day it was. Very, very hot. I could smell the Eucalyptus sap that spilled out from the trees around the field. It made me dizzy.

After two more sprints with Fred I told him I was no longer going to try and run faster but I was going to run better, meaning I’d work on my pass routes. But by no means would I smoke pot. I was still against all that.

“Football was like life,” our coach would tell us. “There is a right way and a wrong way. There are winners and there are losers.”

It was clear to me that he also believed that a person was either fast or slow and he very well had his mind made up which one I was. What else was I to assume but that in football as in life slow was bad and in football as in life you were stuck with the way you were and there was no getting around it. In other words, routes, who gives a fuck?

The hardest part about riding the bench was knowing that your name was on the back and all the girls could see you sitting there like a scrub. Sure, you could stand or move around, pace the sidelines or stretch your legs as if at any moment the coach was going to call your number and throw you out there beneath those lights. But if you did that, I discovered, you might lose the only angle you had left in order to woo a girl. It wasn’t much, but it could work.

“The coach just doesn’t like me. He thinks I’m much too much an individual,” I’d tell them.

I’d really milk it after that. I’d sit way over on the very far end of the bench. When the play was on the one-yard line, there’d I’d be, way over on the other end, sitting on the bench, alone.

“Why is he like that, off by himself?” the girls would ask each other.

“He’s an individual, according to his coach”

“A rebel,” one would surely say.

“Like Steve McQueen.”

“Like Cool Hand Luke.”

I’d sit and stare beyond lights, feeling their eyes upon me. I’d make them wonder what I saw out there in the dark, something mysterious, something only an individual knew how to see. After the game was over, win or lose, I’d walk with my head down, pretending that the whole damn thing had nothing to do with me.

Of course, the ones who scored the touchdowns would get their share of girls, the run of the litter if you will. Followed by those who’d seen a play or two. The rest who stood along those sidelines would up with nothing. Me, the individual, well, there’d always be one for me. All or nothing, just like life, right coach.

That was the plan, anyway. At first it didn’t work so hot. When the chicks saw me staring into the dark they thought nothing of it. It will take some time for things to register, I told myself. Game after game, week after week, they saw me sitting there all by myself, but soon they began to wonder.

After every battle, a crowd– parents, siblings, friends, and girlfriends— gathered outside the locker room and waited for us to shower and then emerge in street clothes. With two games left in the season, I was still being greeted by only Fred. But I heard the whispering. I heard the rumblings. Huddled together, the girls looked, but then quickly turned away.

“What’s all that about?” said Fred.

“You’ll see.”

The final week, after a game we got demolished 35 to 6, Fred met me outside the locker room as usual, only this time he had his baby sister with him.

“Hi Paul,” she said.

“Hey.”

Then she asked me what was with the sitting off all by myself like that.

I smiled. Maria had a great body. Big tits, nice ass. The whole nine yards. I shrugged my shoulders and gave a nod, as if I knew but didn’t know all at the same time.

“We’re going to go get wasted,” she said. “Want to come?”

“Sure,” I said.

That night, partying with Maria, it occurred to me how Burt usually had a girl, one girl, at a time. These days he was seeing Dinah Shore. Looking at Maria, her big brown eyes, her youth, I thought, not bad Paul, not bad at all.

“Your father was tough,” my mother would often say. “Boy was he tough.”

Then she’d get down in this sort of football looking stance and put a grimace on her face. I could imagine him being tough back in those days and every so often I could imagine him being tough in these days too. But mostly I saw him being kind and soft spoken and reasonable. It made me wonder if mom was blowing his football prowess out of proportion a bit. I wondered why she had a need for that. Then I found out why. I was home watching The Phil Donahue Show one afternoon. This was after football season. I had little much else to do. Mom had her bucket and her gloves and all her cleaning products. It was a typical afternoon. Until she stopped and saw who was on the TV screen. Sitting there with Donahue, sitting on a stool upon a stage, a microphone in his hand. Mom stopped what she was doing and wouldn’t look away. How cool he looked up there, Burt.