I think about dying a lot these days.

But mostly that my crush Sheila might catch me dying. I once heard her tell another teacher that the sensitive boys are her favorite, though I don’t think that means sick boys.

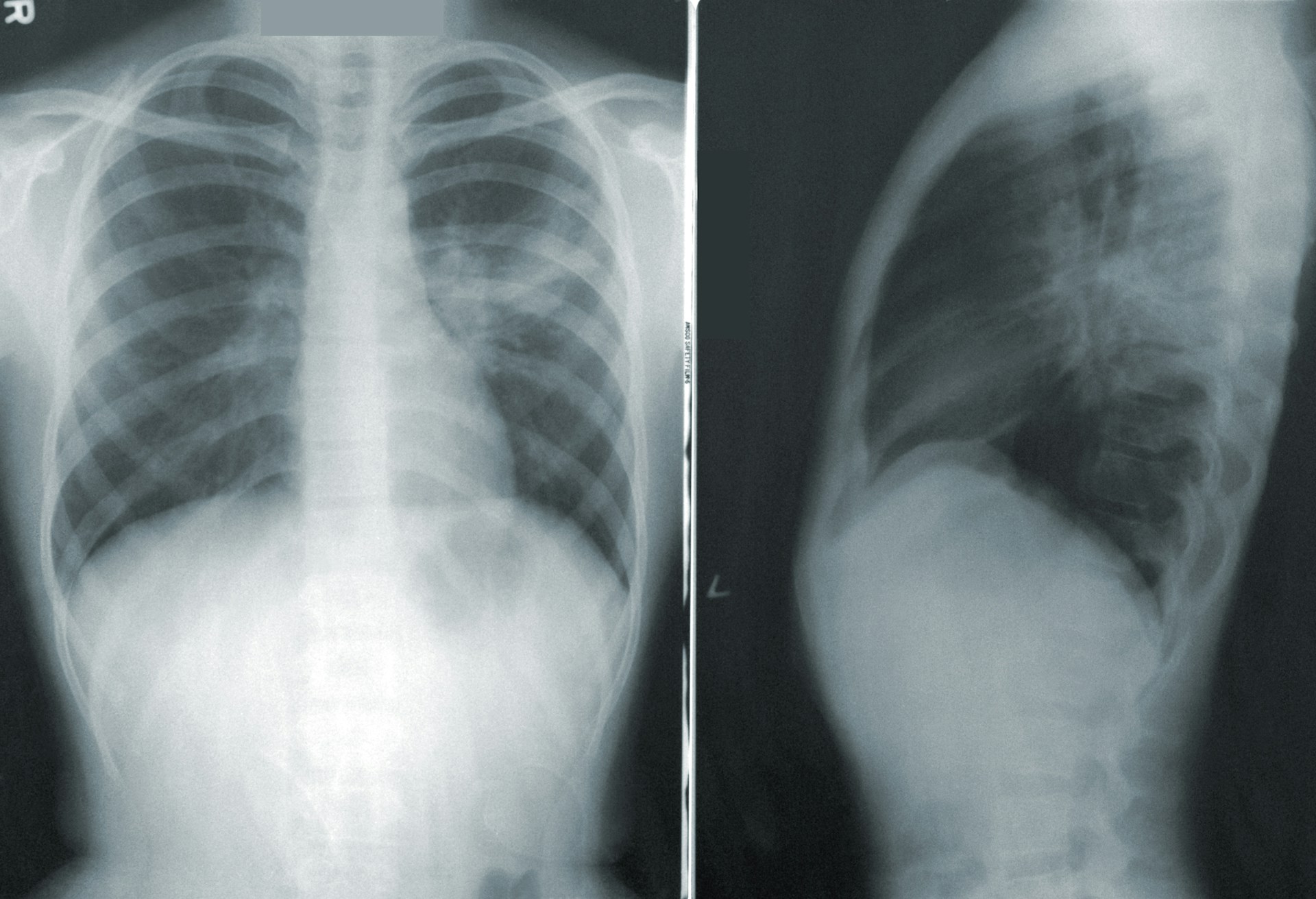

When I was ten, the doctor told me I had asthma. I’d been jumping on the old mattress in my best friend Jamal’s basement, because neither of our parents would buy us a trampoline, when my lungs gave out. As flimsily as the dust clouds that had filled the air. That’s why I had to sit on the doctor’s crunchy-paper table, breathing in and out of a loud, crinkly plastic accordion, while he pointed to an x-ray of white branches. He called them broccoli or bronchi or something. It reminded me of the decision trees I’d learned about in math that week, and I pondered all the ways this asthma thing could go. I already had to walk a part of the mile run while the other boys, and even some girls, lapped me. The doctor folded the accordion up, crunching like a bag of chips, and pressed it into my palm. Not to worry, he said, most kids grow out of it.

Well, I’m eleven now and I’ve grown two inches. And I still have asthma and the stupid inhaler.

The thing is, it’s only gotten worse. The asthma, yes, but also the fact that I have to worry about Sheila now. I doubt she’s noticed me much yet, it’s only been three weeks of the fifth grade. But I’m not really setting myself up for success here because I’ve already had five asthma attacks in class. I know exactly when it’s about to happen. It starts in the back of my throat, like I swallowed a wood chip and can’t get it out—no matter how much saliva I suck down or how much I cough it out. I do try to quiet-cough into my shirt first, so I don’t worry Sheila. The dry wood chip, though, it keeps cutting off more air as it works its way into my lungs and my eyes begin to water. They’re not real tears. I know sensitive boys cry, but I just don’t want Sheila to think I’m too emotional. This is, however, the point at which I wonder if I really am dying, and I’ll admit, that thought usually makes my eyes water for real.

So I have a decision to make. I know I should pull out the plastic accordion inhaler, let it inflate and collapse like my own reputation in front of Sheila. But instead, I raise my hand, squeak the word “bathroom” with whatever air I have left, and run into the hallway until I can use my stupid inhaler where there’s no one around.

The third time this happened, Jamal asked if I’m really not making this more of a problem than it needs to be. Because he’s my best friend, he tries to turn this into a good thing and says maybe I could make it seem cool, like I’m smoking the inhaler. But I don’t know, we just finished D.A.R.E., and Sheila seemed pretty into it.

The last time I had an attack, I didn’t make it out of the classroom though. I fell out of my chair just as my eyes started to water. And the only thing I could see clearly as the room got blurrier was Sheila’s face directly above mine. Oh honey, we’ve got to get you to the nurse, I heard her say. I felt my head nod yes, but really what mattered was that it was just me and Sheila. Her long hair fell over her shoulders and brushed my cheeks. I wondered if she might bend down and go mouth-to-mouth on me if I let out a few more gasps. She was already so close to my face that I could smell sweet strawberries on her skin and mentally noted: strawberry lotion for Teacher Appreciation Week. She’d like that. She deserved it. She’d left her important job at the whiteboard and turned away from the rest of the class to be with me. It wasn’t exactly how I imagined our first solo encounter, but my decision became clear.

I don’t know how many more inches I have to grow until I grow out of my asthma. And until I do, these attacks are going to keep happening. I used to wonder why I couldn’t be dying in the living room where it’s just my parents, or the backyard where it’s just my dog, or the doctor’s office where it’s just my doctor, or at Jamal’s house where it’s just Jamal. But I am a sensitive boy now, a romantic.

The next time, it might not be so bad if it is Sheila who catches me dying. At least, I’ll leave an impression.