When I saw Lauren Bacall at Chasen’s she said that Ernest Hemingway had lost his mind and that his wife had threatened to shoot her. She’d just returned from Biarritz. She’d been in Biarritz with Slim and Slim had said that Ernest wasn’t doing well, and wasn’t it sad to see him like this, what with nobody knowing and what kind of wife threatens innocent women with a gun anyway? And it was a real shame because the summer party season in Spain had been “lovely,” that had been her word: lovely.

Then two-years later I heard on the radio that Ernest Hemingway had shot himself. I wondered what Lauren Bacall had to say about that, but I never asked her. Another question I’d wanted to ask her was whether she’d remembered meeting me there, at Hemingway’s birthday that dangerous summer. I wanted to ask her that and I wanted to ask her if she remembered some of the other tragic things we’d seen there. When I thought about it these didn’t seem like appropriate questions and when I was drunk enough to ask her the questions I wanted to ask I never remembered to ask them. So I never found out what Lauren Bacall or Slim Hayward thought of Hemingway’s suicide, or whom they thought that we should blame.

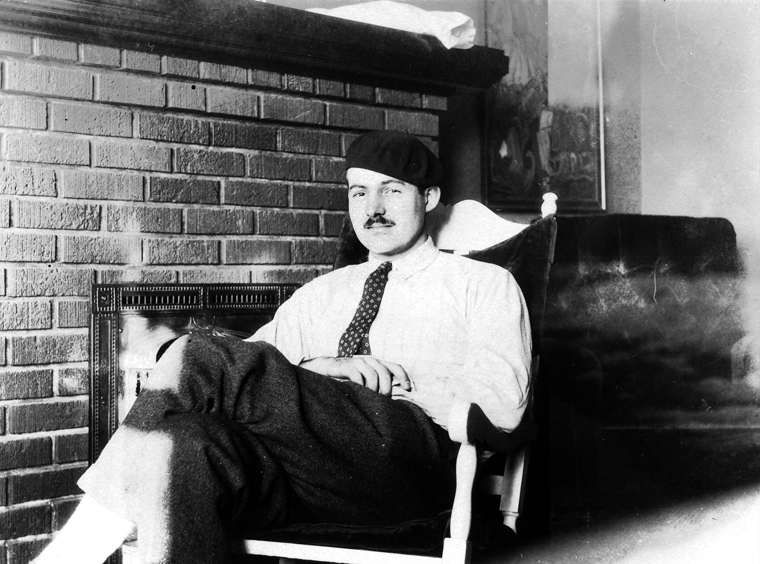

That had been the most dangerous summer. He’d called it that. Life Magazine had commissioned him to write a 10,000-word coda to his earlier book, Death in the Afternoon. He’d been very excited by this commission. He looked forward to revisiting the old corrida, to seeing the old sights and remembering when life had been true. He’d gone to the Abercrombie & Fitch store on 5th Avenue and purchased some new gear—new boots, new shooting glasses, new leather gloves of a very fine grain—before boarding the Constitution for the voyage. He’d been studying the papers avidly, preparatory to writing, examining the looming rivalry between Antonio Ordóñez and Luis Miguel Dominguín. He felt almost twenty-four again; he could hear Hadley’s voice but he never told Mary that part, and he could hear the great roar of the crowd and he remembered how he had been very still the whole time, during that disastrous trip, and made detailed inner notes while his friends drunkenly squabbled so that he could write this all down in a beautiful novel. And that novel—he’d written that truly, with the precise words, and the critics had caught on that, had noted his taught and muscular prose. The critics hadn’t been too kind since, but he would show them now with this new book.

They arrived in Algeciras in May and met Bill at the dock. The Smiths were a lovely couple who had always appreciated him and as a consequence he had always appreciated them. He’d laughed and Mary had laughed at the sight of Bill in that silly pink rental. Bill had called it the Pembroke Coral because of its dark pink hue. They’d piled into the car for the drive to La Consula. La Consula looked like a place to stay. Large and expansive, with multiple verandas, he could imagine getting a lot of work done here. He had a lot of work to do and he felt alive in the work, there were no lies in the work, unlike in life. There was no one telling him that he was wrong, or reminding him that he couldn’t handle so much wine anymore, as if he was some kind of rummie like Scott had been. That was why Scott was dead, along with that vile bitch Zelda, along with his career, and he was still writing, and writing more truly than ever. The paintings on their walls reminded him of those days too, the sight of Picasso’s work and the others, men whom he had known when he’d been just a kid, living with Hadley above that damn dance hall.

The house had been built in 1835 and in many ways it had never entered the 20th century; it had no telephone or radio, Bill explained, as he drove them up the hill and the scent of flowers greeted them, borne on the wind that raffled the delicate palm fronds overhead. He’d reached over and clutched Mary’s hand in the backseat, in a way that Bill couldn’t have seen in the mirror unless he had tried. But we’re going on to Madrid, he piped up, aren’t we Bill? I want to join the Ordóñez.

We are, Bill said. We’ll drop off our bags and get ready, and then it’s on to Madrid. They stayed for ten days in Madrid, for the San Isidro fights, before following Ordóñez first to Córdoba, then on to Seville and Granada. Annie Smith took Mary away after Seville. Some of what we saw frightened us too, the excesses, not just of the gore, for that was one of the bloodiest summers in many people’s memories, but of our own retinue. Ernest was drinking more and more, making less sense, his work becoming terrifying, growing uncontrollably like some form of literary cancer, until an assignment for 10,000 words grew and grew until it broke 100,000 words. We could see how it shamed Mary when Ernest told the same story more than once, easily more than twice, and how painful it was for her when he would repeat some of them five or more times over the course of a night, the only excuse being dawn.

Mary confided in one friend that she couldn’t handle it anymore, the things that no one else seemed to see, the repeated stories, the wine spills, the strangers whose only value was the affection they bestowed on her husband because of what he could do for them or because of what he had written, the fact that her husband was only sleeping four-hours a night. We were all, or many of us, becoming frightful or tired, though our exhaustion seemed to deepen the lower down the scale we were, so that the wealthiest members of our party never seemed to tire of any of it. In fact it seemed to give them life, this midnight feasting on the great artist. That was when we realized that he was another one of their possessions. We also realized that maybe he didn’t know it, though any of us who later read his Paris memoirs knew that he knew something about the rich.

We were almost relieved when a bull gored Ordóñez at Aranjuez. Things had become strange by then. A young Irish journalist named Valerie had meant to interview Papa in Madrid and had somehow become his secretary and assistant. She must have been terrified the night her literary idol entered the women’s hotel room in Pamplona naked and announced that he was there to show them how a real man was built. None of them could believe it but none of them would discuss it, doing so would require admitting certain hard truths that none of us wanted to admit or even conjure internally, at least not until we had returned to Hollywood and the sanctuary of Chasen’s.

So we all ended up back at La Consula, with a gored bullfighter and his wife and his cuadrilla, and that was when Slim Hayward sent him a telegram and said that she and Lauren Bacall were in Grenada. Mary’s face was a study in a Renaissance painting as it crumpled and she slunk off. Ernest sent them a telegram in return: join us. I didn’t know what she was worried about; Ms. Bacall was clearly obsessed with Dominguín though she did tell Papa that he was beautiful, both she and Slim did, but that was what fantasies like them did, wasn’t it? It couldn’t have meant anything, though Mary’s eyes hardened for most of the rest of that summer. We all felt bad for her, though most of our pity had almost nothing to do with the women, the actresses, and more with everything else that we saw. That summer may have been one of the deadliest, with the high winds confounding the matadors in their manipulation of the Muletas, the red cloth flapping every which way, but what I walked away with from that summer was that there were far more terrifying things than eviscerated innards, like wrecked minds that no one seemed to want to acknowledge were wrecked.

The sounds I remember included the endless Fats Waller records and the sound of Ernest’s typewriter as he worked early in the morning. I remember meeting him alone for the first time when I walked out on the upper veranda one day and found him there, nursing a glass of what could only be champagne. It was nine a.m. and I noted the three bottles lined up in three ice buckets, the one empty, the one dying, the other still full. He spoke to me. I was a nobody, somebody’s brother, but when he found out that I was a writer and had written a short story that had recently sold to a magazine we both knew he became interested. I discovered that he was fairly magnanimous, which contradicted a lot of what I had heard said about him, but later I realized that he could feel magnanimous to me because I so clearly represented no threat. I was not a potential rival.

He dismissed writers, telling me that he had defeated Stendhal and Chekhov in the ring, and though he had not yet taken down Tolstoi he would, showing me some moves, admittedly, impressive, the old boxer showing, miming a snakelike jab and a cross that would have knocked me out cold. I wouldn’t have wanted to be Tolstoi in that moment and standing on that verandah. He frowned when the second bottle emptied, despite having a third, and turned to me. “How do you like it now gentlemen, how do you like it now,” the words blurring together toward the end, rising in pitch, and that was when I knew something horrible, and wondered how many other people knew.

We were the only ones awake, I suspected, because he had regaled us until dawn. Every day was to be a holiday: lunch at four, followed by a siesta, before we piled into cars and drove to the Miramar for cocktail hour. Dinner was late, at eleven, followed by hours of stories. He told us how he had secretly been a colonel in the OSS, fighting Nazis, and how this had followed the time that he had sunk a German submarine off of Cuba. Ernest had fought bulls and even been an assassin, and after that morning I took note of how often that peculiar phrase peppered these midnight reveries, these fictions so poor they were unprintable: how do you like it now gentlemen? How do you like it now gentlemen? Sometimes pausing in between each word for emphasis.

The night of his 60th birthday reminded me of certain Errol Flynn films, the ones with jungle sacrifices, the ones where things moved toward a conclusion drummed out that no one would want to see, if it were, if it wasn’t fiction. Spotlights trained on topiaries and the lawn, strategically placed, lantern lights, flickering flames, and Mary had commissioned an entire orchestra, as well as flamenco dancers. One of the dancers was trying to explain the duende to me when the shrill arc of a shell precipitated the explosions of fireworks. I couldn’t help but feel later, too, by the way, that I saw duende reflected in his face. That had been how I had understood finally what duende meant: by looking into Ernest Hemingway’s face, and his eyes, and especially when he made a face that he only really made when he thought that he was alone. I knew then what it meant, to bleed slowly from the heart. And I also knew something else, and that was that a day would come and not far off when I would never see Papa again, and the headlines would be tragic, and this thought so discomfited me that I slunk off to the shadows.

The big man shot a cigarette out of Ordóñez’s mouth. I didn’t see it but I heard the shot. It would have been fine but we all knew how drunk he was, and some of us had even heard how badly he had shot the last time he had gone to Africa. Mary’s face was a study in calm and measured rage. The dinner had been stellar, that had been what Slim Hayward had said, “stellar,” and it had been too in my opinion, a bit unexpected. They’d served seafood dishes in the traditional Spanish style but they had also flown in nearly a hundred pounds of sweet and sour turkey, because apparently Ernest and Mary shared a love for Chinese food. There was Rosé, and Perrier Jouet, and whiskey, and gin, and then we all ate from a massive tiered cake that the servants wheeled out on to the second floor verandah, where we all encircled a table so long that it sat 45 equidistant and with more than enough elbow room. There were two Maharajah’s present and one of them invited Ernest to shoot tigers in India, an invitation I heard myself later, when it was extended, and which I suspect may have prompted the great cigarette shoot. It was okay. Ordóñez took it in stride. He couldn’t get over the fact that a man and a celebrity like Ernest was infatuated with him, and Ernest’s charisma made almost everything okay.

Later, after I had read about how he had risen one morning and, instead of taking a drink, (and I can imagine that struggle after what I had seen on the verandah, with the massacred champagne bottles), walked down two flights of stairs and fetched his shotgun from the gun case and methodically loaded two shells and propped it on the floor, in his vestibule, and leaned down and pressed his forehead against both barrels and squeezed both triggers I wondered if that was what he had thought of, at the last.

Later, after I had published several novels and had the money I visited Ketchum and I knew what I wanted to see most of all: the view, that final view. I couldn’t help but think of Robert, Robert Jordan, with his shattered femur and his severed femoral artery, laying in the copse of trees at the end of that book, clutching the Browning automatic and goading himself on between exertions of courage—that he could do it, he could just do it. It would be okay. The others had gone and fled. No one would hold it against him. It seemed to me, standing there, that perhaps too much duende can flood a man’s heart, too much can accrete, and the only solution is a Browning or the bottle. I couldn’t help but think though that in the end Ernest had left us with the impression that Robert rejected suicide, and instead laid down and cradled the rifle and fixed the sights so that they centered on Lieutenant Berrendo, “just up then from the fighting in the forge,” and that the moment we left that world with Ernest that Robert depressed the trigger and pumped a fistful of lead right into the enemy’s heart, and not his own head.

You can do it and everyone will forgive you. If you bleed out before the time comes then the alternative is anguish. But you’re not any good at this. No, not any good at this. I wondered what kind of man would preface his own suicide decades in advance, describing the way that he would do it, the way his final thoughts would unspool. But when I took in the view I wondered. I couldn’t imagine a more dismal view for a man who had lived and seen and done everything. I thought of the gunshots ringing out over all of this emptiness, and realized that somehow this would make all of this more meaningless.

When I think of Hemingway I think of the dimensions of such a man: already massive, towering, all six feet and two inches, all that muscle that had ultimately gone to fat, those roving and wild black eyes that could silence a room. But I thought of the other dimensions, the worlds he had taken us to, the sights he had shown us, and not even exclusively in his fiction, but in the way that he allegedly lived. I couldn’t help but feel that he was an awfully large presence for such a mortal man. It angered me that no one had helped him, or told him, or done something or anything, even as incorrigible as he could be. It angered me that people tried to keep the party going when the guest of honor was so obviously gone already.

They’d known, we all had known. Slim had said when she had returned from Biarritz that fall that Ernest was swinging wildly from depression to outright madness and back again. It was there in all of the empty glasses and the empty eyes and the stories told so often that sometimes they overlapped, repeated right on top of themselves. But that didn’t make it fair, or right.