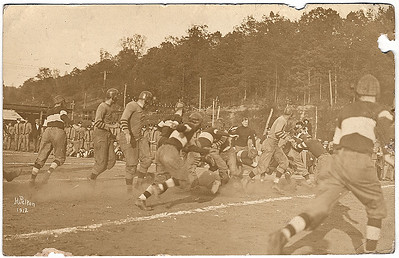

In Texas, football is a religion, with elaborate ritual and fanfare. I was scrawny in middle school; one of the shortest, skinniest and weakest kids in town, I still laced up the cleats each fall. If you happened to be good at the game, say a quarterback or running back with speed and agility (i.e., if you could score), well, you were set—automatic and virtually impenetrable popularity. It was akin to being a noble lord in the feudal era. We all came to the field, to sacrifice our bodies and souls. Most of us ended up in the mud, bruised and bloodied, just like those old-time peasant serfs.

We always started with calisthenics. After that came the most important rituals in the game – tackling drills. Recent decades have taught us what it does to a boy becoming man when his head is smashed repetitively each fall for two decades. So the tackling drills of my childhood have all but been erased. Certainly my two least favorites are long gone.

The worst drill involved being matched up with a teammate of comparative size (I was always smaller). You stood across from this “equal” and folded your hands across your groin. Then your buddy got a running start and tackled you according to a particularly orthodox and exact pattern, putting his head in your chest and simultaneously reaching his arms around you and pulling at your hamstrings so that you toppled straight back. The net sum was a heavy blow to the sternum followed by landing square on your back with you buddy’s weight crushing you. If you were extra lucky and placed with someone who really pulled the legs, the back of your head would bounce on the ground and start ringing. No one knows how many undiagnosed concussions we had in those days.

Occasionally you might be paired with a poor soul who’d give the silent nod, hopeful you’d be willing to exchange mediocre tackles. But this was rare. The only thing worse than lazy fundamentals was cowardice. So what it hurt, the cost of learning the form was worth the pain. There was a bonus too—the primary virtue of football—toughness, courage in the face of agony and hardship.

When I was six I played football in Grapevine, Texas, where the college football selection committee decides who is worthy to compete for the NCAA championship. During one game there, a teammate’s hand was smashed between two helmets and it was bleeding everywhere, pretty much freaking us all out. I could see the wrenching pain in the kid’s face and it made me want to cry for him. Well, the coaches gathered us round and put this kid in the middle and basically worshipped him for his toughness. He’d kept the tears behind his eyes.

After that a bunch of us climbed the bleachers and threw our helmets from up top and watched their slow decline and then they bounced harmlessly off the mud and grass below. I’d like to say now it was some kind of anti-violent protest, but really we just wanted to see what would happen. Well, none of the helmets cracked when they fell, so we figured they were protecting our heads just fine. Young fools.

My other favorite tackling drill was basically training for the real players, you know, the soon to be heroes. They split us into two groups and sent all of the defensive backs (fast guys who were too little) to one line while all of the linebackers (real football players) formed another. The first time the coaches explained my job, I was dumbfounded.

“See that cone over there? Well, you’re gonna sorta head over there about three-quarter speed and a linebacker is gonna practice tackling you on an angle. Get it?”

Already shaking with the anticipation of the coming blow by a boy twice my size, I nodded that I understood. Then I did my job, jogging to my doom. But something instinctual happened that earned several trips up and down the bleachers. See, when the behemoth was homing in on me, I flinched, planted a foot and evaded the tackle, sending one of the football studs sprawling, to the delight of my fellow cornerbacks. They were dummies like me.

After my punishment, I was back in line, and I’d learned my lesson. Now I simply ran toward my fate like a stoic. I cannot quantify the pain of being smashed in the ribcage, lifted from the earth and plummeted back down several feet away, a giant thudding atop your meager frame. A moment of thundering dread, followed by intense agony and the inability to breathe. And of course, lots of blood.

In those days, the most utilized play was either power sweep right or power sweep left. They’d send two huge blockers out on the edge followed by the running back, and try to get all the way around and then outrun the defense. I played cornerback so my job was stay outside of the ball, to hold the line, force the runner back towards my teammates. We practiced this ad nauseam each day and I, being a second-teamer, was faced with trying to stop or deter not one, but three monsters. They were usually either the biggest or most athletic (sometimes both) kids on the team. Yippee!

Now, despite being a runt, I did have a quick first step. Sometimes I’d see the sweep coming (I was a real prophet) and I’d jump the play and hit the runner behind the line of scrimmage for what should have been a loss of yardage, but nevertheless turned into massive gains. One time I got flattened, but I held on to that jersey for dear life. I dragged behind that guy as he ran up the sidelines for twenty yards, like he was pulling me on a sled. Another time the ball carrier kind of threw me on his back and ran down the field with me hanging atop his shoulders like Curious George. I didn’t even slow him down. Most of the time I just got plowed over and the ball sailed down the field for a touchdown.

“Kilgore, what in the hell are ya doing? You know you’re supposed to turn the damn ball back inside, right?”

Wiping blood and dirt from my hands, I’d mutter – “yes, coach.”

Then I’d go out and get slaughtered again, and again, and again. No one forced this suffering on me. This was no prison camp and there were no armed guards. I’d volunteered to be endlessly steamrolled, day after day, year after year. If I could go back, I’d probably play again.

Even if you were a mere bench player, like me, you still mattered, because you were on the football team, and every game day was a celebration filled with hoopla, ribbons, and most importantly, attention from the girls. Okay, so maybe not the second-teamers, but a fool adolescent boy has aspirations.

It’d be a lie to deny the powerful urge to fling one’s frame into violent contact. That was appealing too. There is little more physically exhilarating than crushing a ball handler. I must admit this truth.

There were other benefits.

If we had a travel game, it meant missing half of my academic classes for the day. Priorities. On the way back from the game we’d stop in a roadside Sonic for a Hunger-Buster and fries, and then we’d sing “99 Beers On The Wall” and tell ghost stories until we got back home, late.

I swelled with pride every single time I put on my jersey. Over the years I wore the numbers 88, 20, and 32. Only stars got to pick and keep the same number each year, but I was always lucky in what I received—all numbers I liked.

On game day, the coaches tried to get everyone in, even us peons, and that was the pinnacle of everything. Sometimes I didn’t play but if I was lucky I’d see the field for a handful of plays and these were like gold. I tried to make them count, prove to the coach that he could risk me seeing the field a few more plays next game.

One night we were playing our rivals, the Pampa Harvesters, and the game was winding down. I must have really been hounding the coach with my puppy dog eyes, because all of the sudden puts me in with a little over a minute in the game and us leading 7-0. They were on their own twenty so I guess Coach figured they didn’t have time to score anyways.

“Kilgore – whatever you do, don’t let ‘em get behind you!”

So off I went, and happy as I was to be in the game, I was about to wet myself with fear. I mean, I was playing with the game still in the balance. Usually when I got in, somebody was getting slaughtered, so I couldn’t screw things up. But in this situation, the pressure was on.

Back in those days teams almost never passed. Well, the Pampa coaches must have seen a skinny corner barely big enough to hold up his helmet come in and figured they’d throw long. And pretty quick a huge running back went running past me down the sidelines. Somehow fear of failure helped me reach speeds I never knew before and haven’t known since. I ran that boy down and broke up the pass. If I was honest I’d admit the ball was underthrown, but that would kind of steal my thunder. I ran fast, okay.

I looked to the sidelines and Coach must have only seen the end of the play, because he was clapping and screaming what a great job I’d done. I was certain he’d pull me, but he left me in. Now my juices were really flowing.

The next play they sent a big kid my way and he just took off, running down the middle of the field, looking for a pass. But I wasn’t going to get beat again and I tore off after him like a wild dog. He couldn’t pull away and I was feeling so proud until I saw him looking at me and sort of slowing down. Then I heard the roar of the crowd and my coaches hollering.

Turning, I saw two freight-trains running down the sidelines and I broke away from the receiver to cut off their free run to the end zone. I was the last Borger Bronco who had an angle to make the play. It was all on me, and I knew that I was too small, too weak. There were two of them, each double my size. Nevertheless, I charged toward the moment.

As they neared, I heard the rumble of their heavy feet and saw the laughter and malice in their eyes. Who was I, a mere bench-warmer, to mar their perfect finale? I flung myself head first and arms wide, toward the lead blocker, and closed my eyes. What happened next remains a blur. There was a collision and I gripped tenaciously after jerseys, flesh, bone, fingernails, hair, anything. I was spinning and flying, and to my sensibilities, going the wrong way. But I heard a whistle, a groaning crowd, and my coaches shrieking jubilantly.

I opened my eyes, but still couldn’t see. My helmet was smashed down over my eyes. I lifted it to see that miraculously, I had taken down both the blocker and the runner. My coach was red-faced nearby, spitting and jumbling his words with glee. One of my shoes was missing and the sock on that foot was sagging down, hanging off of my toes. When I finally found the shoe it was back up field, presumably where I had been run over. I scrambled back and tried to pull the cleat on, but it was still double-knotted. As the clock ran out, my coach pulled me to the sideline and gave me a hug. I was surrounded by teammates who heartily slapped my back and helmet and butt. Smiles and laughter were in each face. I’d saved the game.

I was a hero.

Riding home on the bus that night, staring out onto the field as we pulled away, I felt euphoric warmth radiating in my chest. It was a sensation I’ve known only a few times in my life. I belonged to the team, and they belonged to me. I was a pretty crappy middle school cornerback. But on that bus ride home, I felt like the greatest player in the world.

Decades have passed, some of the guys went on to be stars in high school, and a few even played in college. We’re all retired now, and many of us have own children playing football, baseball, basketball, and other sports. I’ve even had the pleasure of coaching my boys a time or two. And after all these years there is still a sort of fellowship; its fun keeping up with old teammates, sharing how our beloved children are experiencing our love of competition, discipline, and camaraderie. The tribal cohesion of the team is still strong, and potent for good, I think.

What’s weird, though, is to see how many of these old teammates—black and brown and white—who sweat and bled together, who pulled hard, often to complete exhaustion in the same direction, now share political posts that are diametrically opposed on racial justice, immigration, election fraud, vaccination, or abortion. We’re often on different teams now, and the rivalry is filled with ever increasing angst, sometimes hatred.

Disagreement is fine, part of the American experiment. Iron sharpens iron, dissent should further our dialogue, make us better. It kind of seems like those brutal old tackling drills, though. It feels like its only purpose is to inflict pain. Bludgeoning sophistry, many of the memes we see these days eschew any desire for real communion.

Modern football teams still tackle during practice. They still create resistance, real conflict, so that when the lights come on, their players are ready. Gone, though, are the days of the meaningless blast. If there is too much risk of injury, the drill is set aside.

In recent months I’ve retreated from social media for extended periods of time. It’s just become too much, and I have high blood pressure, for real. When I start reading all the political posts or worse, the ridiculous and inflammatory political memes, I can’t help but stress, and if I’m feeling particularly imprudent on a given day, if I forget that the author was once my brother, my neighbor in the grime and mud, the blood and sweat, through wins and losses, I’ll post a comment of my own and get sucked into the vortex of wordy non-communication and angst. Like a tackling drill partner, I square off to give intellectual-emotional-spiritual concussions. What will be the long-term effects?

The problem is dangerous, not only for my poor overworked blood vessels, but for my soul. See, when I start reading posts, it is very easy for me to start judging, and I believe it’s wisest to walk in humility, and to extend mercy.

To my nearly fifty-year-old rational mind, the sacrifice I made to get that one middle school football moment of fleeting prominence might have been too costly. It probably was. But there is another lesson, another note that needs to be observed. I wanted to feel part of something bigger than me, something grand and wonderful. West Texas football seemed pretty great back in the 80s, and I was desperate for inclusion.

Need for acceptance is one of the most powerful forces in the world. People do and say all kinds of crazy things for approval from their team or tribe or political party or religious group, and if I look only at their overt pursuit of that quest, without considering the desperation of their lonely heart, it’s easy to forget they’re my neighbors. I have also been brash and reckless, not infrequently. A loner and eccentric, I still want to be cherished.

Sometimes it takes one lonely soul to find another. It takes mercy, kindness, and outstretched arms that promise a harbor, a place to belong. So—look to the fools, to the valiant nincompoops you see online and in the flesh, and offer an open hand, merciful eyes and a friendly smile, however difficult it might be. You never know, you might be the only lifeline they’ll get. And who knows, maybe you’re the blowhard needs rescued. I’m quite sure that I need to be saved, every single day. Lord, have mercy!