First of all, her initials are MF and I think she’d be okay with me calling her a badass MF’er, which is what I’m trying to tell you: you need some more MF’in Melissa Faliveno in your life.

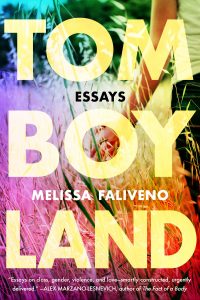

Which is to say, you need to read Tomboyland. It’s required reading. I’m requiring it for you. BULL is too.

And maybe the point I’m trying to get to with all this MF’in business: it’s the shit we identify with whether we want to or not.

In one of the blurbs for the book, Melissa Febos describes Tomboyland as a “complex ode to the Midwest,” and it’s totally that, but I’d also say that really any ode to the Midwest is by nature complex. We’re the type of people who can’t stop complaining about how crappy the weather is, but never move (but also: we’re the state that once got into a fight with Michigan over who gets to market themselves to snowmobilers as the mitten state).

It’s pretty much the same with depression, alcoholism, suicide, Lutheranism, etc. It’s both a great place to grow up and an inborn childhood trauma that we all instinctively learn to repress. Shush! That should be written on our state flag. We’re the type of people to complain constantly about everything, but to stoop to confess our innate mental illness is to whine, and the last thing any true midwesterner wants to do is whine.

Keep yourself to yourself, they say. They also say: Suck it up, buttercup. And: Quit yer belly-achin’.

Author’s note: MF and I both grew up in Wisconsin—her in the middle-southern part and me in the northern-end-of-civilization part—and if there’s any state that completely personifies all these mixed feelings, it has to be Wisconsin, which over the last ten years has been pretty difficult to explain to non-Sconnies—let alone defend it—but at the same time pretty difficult to leave out of the conversation completely.

But then that’s mostly just more of the same. Wisconsin! We have beer! We have cheese! We have two of the most notorious serial killers of the twentieth century (one Jeffrey Dahmer who ate dead people and two Eddie Gein who wore their skins like vests)!

It’s this always slightly awkward sense of the things that make us who we are—the things we are stuck with, things we choose for better or worse—that entwines every essay in Tomboyland. It’s also my favorite part, the intertwining’ness of it all.

It’s food for my ADHD/OCD soul. It makes connections that people without ADHD might not make, which isn’t actually true because I’m pretty sure MF isn’t diagnosed officially. But regardless, for all its detours there are the dirt-road obsessions and compulsions that we keep coming back to. And the whole time you can’t not keep reading to find out how she sticks the landing, which she always does.

Like the one about food, midwestern food, family, and S&M, and if that’s not about the most perfect encapsulation of Faliveno’s midwesty’ness, of Sconnie’ness, then well I just don’t know.

Which all then leads us back to the thread we most frequently come back to besides the idea of place: slippery identity, frequently sexual identity, specifically being bi-sexual and not being able to fit in on either side of gay or straight.

Of looking masculine and being bi-sexual and having a bunch of straight people constantly confusing you with being a man and calling you a dyke and then a bunch of gay people questioning your gay’ness because you happen to be in a long-term relationship with a man.

Of course, this is me explaining this all—maybe even mansplaining it, sorry sorry—from the perspective of a straight white cis male, so maybe I’m getting things all wrong. Which is another fucking reason you need to read this: to let Faliveno let you in on some uncomfortable truths about the way we deal with sexual identity and especially when you come from the Midwest, and all our supposed wholesome salt-of-the-earthiness and then move to New York, where even there you don’t fit in because your too Midwestern, too rednecky, and you can’t even move back home, because once you get off the farm and move to NYC, well, it’s not like any Sconnies will ever truly trust the city-girl again.

Which, of course, I’m not explaining any of this well enough, sorry sorry, but then there you go, another reason you need to read Tomboyland: Faliveno explains all this in a way that even a fellow Midwesterner like me, a fellow Sconnie, can explain with any clarity.

Plus there’s softball, roller, derby, an ode to Twister and the sexual chemistry between Bill Paxton and Helen Hunt. There’s bench-pressing and squatting and farming and the tricky relationship between doms and subs.

It’s all in there and it’s all gritty goodness.

And there’s Melissa Faliveno for you—the true MF’er, Sconnie to the core—how much I’d pay to buy a ticket to ride in her brain any day and so should you.

– drevlow

BD: Can we talk a little about the sexual tension between Bill Paxton (RIP) and Helen Hunt?

MF: Oh my god, I could talk about this forever. Truly, one of my favorite sexual tensions in all of cinema. (And by “cinema” I mean of course the most important canon, Bad 90s Action Movies, and that canon’s king, Twister.) The scene where they’re in the truck, chasing a tornado, and he’s getting her wired up, and clumsily brushing her bare shoulder, and her hair is falling on him and he’s like “Oh, excuse me” all nervously while Van Halen is playing in the background, and Phillip Seymour Hoffman (also RIP) and the character named Rabbit are talking about “TENSE SITUATIONS” over the walkies, and everyone is driving very fast through cornfields and shit? I mean. Come on. Also, who hasn’t dreamed of making out in a field, chained to a pipe, in the aftermath of an F5 that magically didn’t kill you? What a payoff! A release to end all tensions, a love to end all loves!

BD: So I have a fun combination of OCD, ADHD, and anxiety, which means that I am constantly having conversations with about 12 different people in my head at the same time.

Which is all to say, I really loved how your essays manage to weave between three or four or more threads at the same time and always be able to thread the needle at the end.

MF: Thanks! I sometimes think of this particular habit of mine as a curse—like I can’t just write about one fucking thing. It has to go in all these different directions, and it can be really hard to make sense of things. But when I think of the essays I love most, they do this kind of work—they branch out, take weird detours, peer into all these surprising corners. And as a reader, when I’m like, “Oh, why are we here now?” and then the story unfolds like a mystery, or a journey that the author is taking us on, that’s when I really geek out.

BD: And while we’re on the subject, is this how your brain works too or am I projecting too much?

MF: Ha! You’re not projecting at all; my brain really does work that way. (And I too have struggled with both anxiety and OCD, so I feel you.) I think most of my process, in terms of writing essays, is trying to wrangle all the threads, figure out on the page why things are connected in my brain, and see what interesting things I might find in the connective tissue.

BD: How much of your threads come as part of the natural writing process versus you thinking things out ahead of time?

MF: I might be circling around a few seemingly disparate ideas before I start an essay, but mostly the threads, and certainly the connectivity, comes only as I write. Essays for me are really a way to ask a question, often from a bunch of different angles, to see what I might find. I rarely ever know where I’m going when I start an essay, and there’s usually some kind of revelation that happens in the writing process, where I’m like, “Ah, okay, so that’s what I’m doing here. (I think. Maybe.)”

BD: Are there ever times where you’ll make a jump but it feels a little too easy or predictable? Times where the jump makes sense to you but your editor/readers feel like it’s too much of a leap?

MF: I definitely make leaps sometimes that feel predictable, maybe a little cliched. This happens most often when I’m digging into a metaphor. And sometimes I’ll step back, take some distance, go back to the essay and think, “Oh jesus, that’s embarrassing,” and then cut or adjust that particular thread, or line of inquiry. Which is not to say that you can’t write about some metaphorical connection that’s been made before (I have a whole essay about motherhood and plants, for crying out loud); I think the key is that you have to try to take it somewhere new, or surprising, or add some another element to the conversation to deepen the connection.

BD: How much of your jumping comes from a discomfort with being stuck in one thread for too long? Maybe again I’m projecting my own discomfort here, but I was also thinking I could do a whiz-bang PhD thesis on your writing style and how your discomfort with identity informs this? Or am I full of shit?

MF: I get bored easily, and can lose focus on a single subject. And while I can spend hours (read: weeks, months, years) researching one thing, the way I really make sense of a subject is by looking at other, related (however peripherally) subjects—often that I’ll stumble upon in the research process. But really, it all goes back to the idea that, for me, the most interesting ideas, questions, and experiences are multifaceted—I can’t write about gender, for instance, without writing about sexuality, without writing about class, without writing about the Midwest. They’re all inextricably connected for me, and so what I try to do in an essay is tease out all those connections, and try to make sense of them.

BD: I was wondering about your experiences with masculinity/toxic masculinity within female sports? I was thinking of specifically things like the desire to dominate, to bully, to intimidate, the fear that comes with it, the sexism, homophobia, the cycle of violence.

You talk a lot about your own experiences on both sides of violence, so I was wondering how much that played out for you in things like hockey, softball, or even roller derby?

MF: I think about this a lot, and I don’t think it’s something I ever thought about when I was growing up playing competitive sports—even when I was an adult, even when I was becoming more aware of things like misogyny and toxic masculinity; I didn’t know how much I internalized those things. But I grew up around dudes, a lot of my friends were dudes. And as I got better at sports, started identifying as an athlete and winning awards, hanging out in the high school weight room with the football team and competing with them on the powerlifting team, I swaggered around school like those dudes—brazen and braggy and a little butch, before I ever understood what that word would mean to me someday, but still hyper feminized as I knew I was supposed to be—wearing makeup and tight skirts and heels, wanting to be the object of those dudes’ desires. And as I got older, I hung out around a lot of dudes, too, especially those with whom I played on co-ed bar-league softball teams—Midwestern dudes, straight white cisgendered dudes, dudes who drank too much and watched sports and talked shit and loved to chase girls but probably hated a lot of women, who were certainly super homophobic. Who said things like “pussy” and “fag” to each other on the regular. And to roll with them meant saying these things too. I didn’t realize then—and this was in my late teens and early twenties, before I took my first women’s and gender studies course in college, before I started shopping at the feminist bookstore, when I still put “ALLY” stickers on my notebooks, before I had any understanding of my own queerness. I internalized all that shit, and it took a long time to break out of those habits. It wasn’t really until I stopped playing on those co-ed softball leagues, and started playing roller derby, and then on an a women’s fastpitch league—both of which were made up of a bunch of queer folks—that I realized that being a jock didn’t have to be synonymous with misogyny or homophobia. That masculinity didn’t necessarily have to be the toxic kind. That I could embrace my own masculinity more than I ever had—chop off all my hair, stop wearing the skirts and heels and makeup that never felt like me, to be confident and competitive and maybe even a little cocky without cutting other people down, to stop trying to fit into the classic “cool girl who can play sports and drink beer but who still looks good in a dress” bullshit I’d learned from all those men of my past. Basically, to stop trying to play that role to fit in with the men, and own it for myself, while surrounded by a bunch of queer women and people who broke open my own understanding of what a “woman” could be, what masculinity could be, how my own body and sense of self fit into those words or didn’t.

I still like to watch sports and drink beer and talk shit, by the way, but I understand now that I can do those things without being a dick. Which is fun!

BD: My apologies, but I feel like in these times, I would not be doing my due diligence if I didn’t get a little political with you. I know this can be a bit of a touchy subject, but in your mind, how far do the borders of “Midwest” run? Which states that sometimes like to think of themselves “Midwestern” do not meet the qualifications in your mind?

MF: Oh man, this used to bother me a lot more—maybe until I started writing a whole book about the fluid and indefinite nature of literally everything. I used to get pretty irritated when people from eastern Ohio called themselves Midwestern. Like, sorry, no, that’s the Rust Belt. But I’ve come to embrace the Rust Belt as simply another sub-community of the Midwest, like the Great Lakes states or the Plains. One of the beautiful things about the Midwest, I’ve come to understand, is that—like gender, like sexuality, like language—its boundaries are fluid, its definitions change depending on who’s speaking them. What I mean maybe is that it’s murky and indefinite—and those are the spaces I love most.

That being said—someone who had lived their whole life in Pennsylvania once told me they considered themselves Midwestern, and that is one hard line I will absolutely draw.

BD: Okay, so I noticed that you switched terminology once or twice in your book, so let’s nail it down definitively once and for all: Pop or soda?

MF: Hahaha. The most important cultural question of our time! It’s pop, one hundred percent. But the truth is that I code switch all the time, so here in New York I usually say “soda,” (like I say “caramel,” rather than “carmel.”) But as soon as I’m home in Wisconsin, I’m back in the land of pop and carmel and standing in line instead of on it (which—how do you even stand on a line? The people are the line! It’s madness).

BD: What was it like recording the audio for your book? Most of the stuff I write, I write to be able to be performed out loud, but I also know that when I try to memorize pieces, there are all these little things that seem fine on the page but bother the shit out of me when I have to “perform” them.

Were there any words or lines you had written that you then cursed yourself later when you had read them aloud? Repeat them? Stumble over them? Etc.

How much did you have to code switch between your ‘sconnie accent and your natural voice and then your “Audible” voice?

Did you learn anything about your prose from the process?

MF: Recording the audiobook was actually one of my favorite parts of the publication process, even though COVID curtailed all our fancy plans for it. I had to audition for the part, which is kind of wild, and had to send the folks at Brilliance a sample recording of myself reading an excerpt. I got the job, which was super exciting, and I was supposed to be flown out to a studio in Michigan for a week last spring to work with a director and producer. When COVID hit, they were like, “Sorry; we’re going to have to hire an actor out here.” And I was like, “Hang on a minute.” I was stuck at home, teaching remotely, and had a bunch of free time; I’m a musician and used to produce and cohost a podcast for Poets & Writers, so I have a bunch of recording gear and audio experience. So I built a little ramshackle studio in a tiny closet (I know) in my Brooklyn apartment, draped blankets from the walls, and borrowed a fancy mic from my friend who works in radio. I recorded into GarageBand through a little Zoom H4n we’ve got here to record music. I set up a mic stand and the folks at Brilliance sent me an iPad to read from, and a director, Ken Schmidt, Skyped in from Michigan. He was incredible to work with—super pro, and just overall a wonderful human. (We spent a lot of down time talking about our dogs.) I figured out my setup so that he could monitor my recording, and he would cut in to have me do a section over, give a line a little more energy, develop some accents and tonal differentiation for some of the people I interview in the book, which was fun. Lots of Sconnie accents for those parts. For my own part, there was certainly some code switching between Sconnie and radio voice—but because of my experience hosting a podcast it wasn’t that new for me. We focused mostly on energy, and presence—really showing up for it, like I would a performance with my band. The best advice Ken gave me was that it should feel like telling a story—like I was sitting around a fire with friends, telling these tales; that it should never sound like reading. He could tell when I was getting tired, or checking out a little, and we would take a break, and then kick it back to life. There were definitely moments when I would read something and shudder over what I had written, or think—“Oh man, I should have cut that line,” or “I could have written that better.” Which was a little horrifying, but helpful. I always tell my students to read their work aloud, and having to read my entire book aloud—sometimes repeating sections multiple times—was an exercise in both editorial hindsight and humility.

Luckily, because this was the height of the COVID outbreak in New York City, construction was halted—so there was no usual soundtrack of chainsaws and pile drivers and jackhammers, which would have made this process impossible. It was June, and super hot in the city, so I sat in my tiny dark blanketed closet for a week, sometimes recording for eight hours a day, just sweating through my clothes and drinking hot Throat Comfort despite the heat. It was kind of brutal, but I loved it. One of my favorite parts about playing music is recording—being in a studio for days, working with bandmates and a producer, doing takes until they’re right, figuring out some stuff on the fly collaboratively—and it was a lot like that. I’d love to do it again someday. So if anyone needs a deep-ass contralto (or tenor, if I’m being honest?) hit me up.

BD: Can you explain to me the rules and strategies of roller derby? I am always drawn to it, but am also quite dull-witted and have never been able to suss it out.

MF: Totally! It’s a bit tricky, and there are so many strategies I can’t name them here (plus the game has changed a lot since I played, about ten years ago, back at the beginning of the modern-day resurgence). But the basics: there are ten people on a flat track, all skating counter clockwise during game play; each team has a jammer, whose job is to score points, and four blockers, who make up a “pack,” whose job is to both help their jammer get through the pack and stop the opposing jammer from getting through. So they basically play defense and offense at once. A jammer is essentially a sprinter, and her job is to lap the pack, scoring one point for each opponent she passes legally. And everyone is hitting everyone while this is happening, which is of course the best part. I was a jammer, mostly, but I also had a lot of fun as a pivot, which is kind of the leader of the pack; she stays up front, is often the last line of defense, and communicates with her pack and calls out plays and such. I loved to jam, because I love to skate fast, and I was pretty good at it. But I also really loved hitting the shit out of people. It’s pretty much the most satisfying feeling in the world, especially for someone with a lot of repressed Midwestern rage, to slam your body into the body of another person, on roller skates, and watch her fly off the track and into the crowd. *Chef’s kiss.*

BD: I would say that about 70% of my desire to write when I first got started was a rebellion against Midwestern repression, which in my mind is closely related to my relatives’ version of “Minnesota Nice.”

The upshot of this was that when I first started publishing things about my family—no matter how hard I tried to paint them as the good guys to my own bad guy routine—my mother would often write me letters to say how glad she was that I was a writer but then how much she wished I would move on and start writing more happy things. More happy things that didn’t involve her, my father, and my dead brother.

You have a spectacular essay about family, food, and BDSM. And of course, beyond that you are writing a lot about some tough things you have gone through—not in response to anything your family did to you—but still, a lot of things that would make most Midwesterners squirm in their seats. Not the least of whom, I imagine, the people who know you best.

What’s that been like?

Do you have ground rules for what and whom you will write about?

Do you share it with them first?

I’m asking, because frankly, I’m pretty terrible at this, and at this point, my family and I have come to a very Midwestern don’t ask, don’t tell compromise with my writing.

MF: Whew. Yeah. This is one of those things that never stops being hard. I keep doing this thing to my parents where I reveal things to them about myself through my writing—things we’ve never talked about before, things they don’t know until they read the piece (usually after it’s been published), things that we still don’t really talk about—but even though it’s hard, I feel a lot of relief every time it happens. It’s like coming out (which I also did to them through this book) over and over again. I’m an only child, and my parents and I have a pretty good relationship now, but things weren’t always great, and we certainly partook in that long and storied Midwestern tradition of silence—of not talking about anything hard; of denial and repression and grudges and a quiet, simmering rage; of any sort of conflict or confrontation turning into a sometimes years-long silent treatment. And when that’s the possible outcome of conflict, you learn to shut up and never say anything. So I feel like every time I reveal some vulnerable truth about myself, however large or small, we’ve chipped off another little piece of that generations-old glacier of silence. And they know me a little better than they did before.

A hard truth about writing personal essays and creative nonfiction is that no one is an island, and if you write about your life it’s inevitably going to involve bringing other people into the fold—often those closest to you. My students ask me some version of this question all the time: How do you write about your family, or the people you love? And I think my best answer is this: Focus on the story, and stories, that are yours to tell. If you can write something down and honestly say to yourself, “This is my story,” then I think you’re off to a good ethical start. If you write something down and it doesn’t feel like it’s yours—if it reveals someone’s secrets, for instance, and especially if a certain revelation could harm them, or you—then I think it’s critical to interrogate your motivations, and the implications of telling it. It’s also important to ask yourself, “Is writing this down worth losing someone over?” I struggled with this a lot when I was working on my book—so much so that I almost cut one of the harder essays to write, “Switch Hitter.” In an earlier draft, I had revealed some details that I knew could be hurtful to other people, and possibly to me, and might end up in a severed relationship or two. I was really banging my head against that essay, because I felt like I couldn’t tell my story without telling every single gory detail. But at one point, my very good friend and trusted first reader, Melissa Febos, was talking me off this particular ledge. She said, “Try not to focus so much on what you can’t say, and try to focus on what you can.” What parts of this story can you really write into, and bring to the fore, to say what you need to say, maybe instead of these other elements that you don’t feel comfortable writing about? Another way to think about it: What ways can you tell this truth, without necessarily telling all of it? That really unlocked something for me, and it’s advice I give to my students and friends all the time now. There are some memoir purists who will tell you that you have to tell the whole truth, no matter who it hurts; tell your story and fuck everything else. And maybe, for them, that works. (Though I really have to question one’s moral compass if they truly believe that.) I personally don’t buy it. If something feels too uncomfortable to write, you don’t have to write it. And in the end, this is art, and those are lives. To me, the lives are always going to be more important.

(That doesn’t mean you won’t piss people off, even if you try very hard not to. You almost certainly will.)