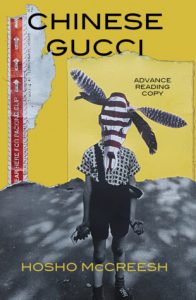

I’ve thought long and hard about how to start all this about Hosho McCreesh and Chinese Gucci, and ultimately I’ve decided the most appropriate way is to cheat.

So here’s what Willy Vlautin said:

“Akira is maddening, endearing, troublesome, wounded, lonely, lazy, and a tremendously enthralling ne’er-do-well. A modern Ignatius J. Reilly selling knock-off Chinese Gucci on eBay. You’ll love him and hate him, you’ll want to save him and throw him off a building.”

Akira Nakimura being the protagonist of Hosho McCreesh’s novel Chinese Gucci.

Willy Vlautin being fucking Willy Vlautin.

Honestly, I’m well aware of my propensity towards hyperbole, sure, but believe it or not, I usually try to avoid throwing around literary comparisons in stuff like this. It’s too easy to play a kind of SAT-question Chinese Gucci is to X, as [Random Book You’ve Heard of] is to Y, which is part of why I’m cheating and quoting Willly Vlautin here. Because, yeah, that’s it. That’s exactly it. Ignatius J. Reilly. Confederacy of Dunces. Chinese Gucci. This is the best I can come up with. What Willy said.

Or hell, while we’re down this SAT-question rabbit hole, we might as well let our our favorite femme fatale of Florida-noir Steph Post weigh in on things:

“A Catcher in the Rye for the twenty-first century.”

Which, listen, I get it. How many times have you read that some new book’s the next Catcher in the Rye or that the protagonist of this some new book is a real Holden Caulfield for our era, and if I had said this myself, then I’d expect nothing less than for you to call bullshit on me, but try to stay with me. It wasn’t some hack like me. It was Steph fuckin’ Post.

And sometimes it just is: a Catcher for the twenty-first century.

And here I am I’m tell you don’t listen to me, I’m just cheating off the tests of the smartest kids in the class and I’m only confirming it for you.

Don’t believe me/Steph/Willy all the other people who’ve already said the same thing? Then prove us all wrong, dickhead. Go read Chinese Gucci. Then afterward, when you’re telling everybody else why they need to read it, you try and describe it without the words Ignatius, Holden, Catcher, or Confederacy.

But also, here’s this: Chinese Gucci isn’t Catcher or Confederacy and Akira Nakimura isn’t Holden or Ignatius or any of the other standard bearers for unlikeable protagonists that readers/reviewers/blurbers reference with equal parts unabashed love and condescension.

He’s this punk kid just out of high school, a little too old to still be acting like such a punk kid. He’s just your typical Japanese-American kid who speaks fluent hip-hop and textese, loves Internet porn and first-person shooter games where you get to reenact the Normandy Invasion and kill a bunch of people without any of the PTSD flashbacks.

The type of kid who’s constantly got his ear buds in loud enough for everybody to hear as he bumps Snoop, 50 Cent, and a random local speed-metal band from Albuquerque called Leeches of Lore who split up five years ago. The type of kid with obvious mommy issues and daddy issues who doesn’t just joke about buying fake vaginas online—he buys them.

He’s the your typical Japanese-American kid who lives inAlbuquerque, New Mexico, who hangs out on weekends in Juarez, Mexico so he can “invest in” knock-off purses made in China and re-sell them on his dead mother’s eBay account.

He’s DIY and a slacker leeching off his parents at the same time.

He’s a goddamn millennial if there ever was one. He’s stunted. He’s America. He’s everything that’s wrong with kids these days. He’s us. And he’s everything about us that we say we hate but deep down we can’t quit on because, well, he’s us and to give up on him would be to give up on every shitty thing about us we’re too embarrassed to admit.

Because at this point, in this country, in this world, yeah, we’re all the unlikeable protagonists of our own ugly satires.

He’s the book that—honestly, all hyperbole and lofty literary comparisons aside—nobody else has written, nobody else could’ve written.

He’s a poet who’s never published a novel before who sets out to write “the great American novel” with no bluster or blushing.

He’s the giant middle finger to every editor or publisher who’s ever said you’ll never sell a book like that. Nobody’ll get it. Nobody’s gonna read a novel with from the point of view of a millennial punk kid that unlikeable, that naïve, pompous, empathetic, and ethically questionable at the same time—that un-pitch-able (i.e. that un-pigeon-hole-able).

He’s the book you need to be reading. He’s the book you need to be telling your friends about.

He’s not Akira Nakimura. He’s Hosho motherfuckin McCreesh (no matter how much Hosho might deny it).

[Authors Note: The following questions are quoted from random things that I cribbed from other interviews McCreesh has given that I have now taken out of context and turned them around as gotcha questions in my attempt to impress everybody with my high journalistic acumen]:

“What are you doing on the roof of my house?”

Benjamin Drevlow: If you would allow me, sir, I think it’s important that we establish something from the start of this whole interview: What are you doing up there on the roof of my house?

Hosho McCreesh: If I’m up there, I’m obviously too far gone to know what the hell I’m doing.

BD: And if I sometimes get drunk and end up hanging out on the roof of my house, too? I mean, what I’m really trying to ask is if you think we could be, like, roof-hanging buddies?

But also: What would be the likelihood of us both falling off and dying/breaking our necks based on your past roof-hanging proclivities?

HM: Definitely. Hanging on roofs is pretty boss… though, these days, I prefer an easy elevator ride, or a nice deck up there. When you’re young, you’re invincible—and climbing rickety ol’ fire escapes or drain pipes isn’t a problem. Then you get older… and mortality pokes you ever so gently in the chest a couple times. These days the chances of falling off are very high.

“I’m not really a ‘writer’ so much as just a guy who writes. I have a regular 40-hour-a-week gig”

BD: What I’m wondering: a). You still doing the forty? and b). Do you voluntarily admit to people that you are a capital W–Writer or do you have reservations about that based on your “regular gig”?

HM: Still working the forty-hour gig plus a little writing work on the side. At least another decade of that for me. If I make it, (and the world is still here) I’ll get retirement. Then it’s tacos and art all day! If I have any reservations about calling myself a “capital W-Writer” it’s that I don’t especially feel like one based on sales, etc. I’m not trying to pretend to be something I’m not. I’ve been publishing for 19 years, but I’m a small press writer. I am a million miles away from New York, and New York is at least a million miles away from me. I don’t know any Capital W-Writers, the kind that movies and TV shows tell me exist. I certainly haven’t bumped into any in New Mexico.

BD: I guess then that brings up c). How does this whole idea of being a “Writer” or a “Working-Class Writer” or simply “a guy who writes” come into play with the types stories and poems you write?

HM: Part of it is who I am and where I come from. Growing up, there were times when we were really poor. Seeing the people around me live interesting and compelling lives, live out stories that don’t typically end up in novels left an impression on me. And New Mexico is a pretty blue-collar place, a place that doesn’t suffer pretentious fools lightly. Most folks here don’t have time or money for poetry books, and probably don’t relate to the vagaries of struggling with multi-generational wealth. New Mexico is a salt-of-the-earth place, with salt-of-the-earth people…so those are the stories I naturally am drawn to.

BD: And well shit while we’re at it, we might as well go for d). I was thinking about Akira’s weird, slacker DIY ethos, and how on the surface we kind of have this sorta typical millennial slacker who doesn’t want to “work,” but then ends up having to hustle pretty hard to live the easy life.

HM: By New Mexico standards, Akira is very much in the middle class—and awash in all the advantages and prejudices that come with it. His parents have insisted he work, and he’s just lost his fast food job… so, in that way, despite being middle class, they’ve tried to raise a kid with a work ethic. But, yes, Akira has also been sold an American Dream that says you can have it all just because. He’s lazy… and yet, innovative… creative. It’s like talent versus hard work: each can only get you so far, so you need both. Akira doesn’t realize how good he has it… which is a very middle-class-American mindset.

BD: Jesus, you know the interview’s going horribly wrong when you get to part e). But here we go: Was that something you had your sights on from the start—this ideal of the “working class ethos” that has been really kind of corrupted in shitty shitty ways by American “bootstrap” culture and politics?

HM: I was definitely out to skewer parts of America that I dislike, and Akira represents a lot of them. But I’m conflicted too, because he also represents a few of the things I think America is good at—or could be. As to the corruption of the working class—working folks simply don’t have the chance to even think of any of this… they just have to work. This “bootstrap” culture is just another kind of lie like the idealized American Dream. The American Dream exists—but it is so much smaller than advertised. I know because I am living proof. When my mom got sick, we spent about 2 years on food stamps. It absolutely kept us alive…but they were tough and tenuous times. With my 40-hr gig, I’m middle class even if half my work is schlepping boxes around. So the American Dream worked—sort of. I don’t have everything… but I do have more—more safety, and security. Of course, as a white dude, so I’ve had it pretty damn easy.

BD: You’ve mentioned Salinger and Holden Caulfield in a few different interviews and it seems like the “abrasive” protagonist comes up a bit with Chinese Gucci, which I understand but it always kind of tickles me, this idea that “the unlikeable” protagonist (versus all those classic novels about “likeable” protagonists).

My whole childhood I’d heard about Catcher in the Rye being banned and how crazy killers read it and then tried to kill people, but I didn’t read it until I was like 22 or something and I remember thinking oh this kid must kill himself in the end or something worse for all the controversy over this.

Then I read it and I guess this really reveals what an asshole I was/am, but I was like, What’s the big deal? I mean really really loved the book in ways I probably wouldn’t have admitted at the time, but also the whole time I’m reading it I’m waiting for Holden to kill himself or his parents or do something really subversive, and then spoiler alert: It’s just that nursery rhyme at the end, which is such a great fucking ending, but at the time, I was like, That’s it? This is what made people so crazy? This is the book everybody’s in such a hurry to ban?

HM: It’s hard to say why Catcher is such a touchstone for both those who love and those who hate it. My guess is it has a lot to do with how subtle Salinger’s work is in regards to death and post-traumatic stress and how, post-WWII, America was wounded in ways it didn’t understand. America was hailed as a savior… and yet, at what price? We sold our soul to end the war… and I think we’ve been searching for it since.

BD: For me I kind of get it, it’s this really pissy, damaged (and definitely privileged to a degree) kid dealing with the death of his big brother and not being able to keep his shit together, but for me that was the whole point, the best part. The most honest depiction of who I was and what I thought everybody was at that point in their lives.

It was like somebody’d written a really great rambling lyrical monologue of how pissy and angry and self-absorbed I was as a privileged teenager dealing with the suicide of my older brother and not being able to keep my shit together, but also knowing deep down it’s not like I had gone to war or anything. Life wasn’t really that bad.

HM: I’m sorry to hear about your brother. The fact that the book has had such a lasting impression on American literature is proof that it found something fundamentally American, something the country didn’t want to admit was there. It might be something about mortality and our refusal to consider the truth of our eventual deaths. It might be how complex the notion of vaporizing entire cities in a single morning to serve some “greater good” was. The book gives us every reason to hate Holden… and yet, there’s something else happening too. If you feel for him, then you really feel for him and seek to understand him. If you don’t, you simply dismiss him. That still sounds very much like America to me.

BD: You are a very good and kind man to humor my bullshit when obviously, this is just me trying to rationalize what a privileged and unredeemable little shit/pain in the ass I was/still am.

HM: Aren’t we all?

BD: What about the process of “Akira.” Were there points during revision or editing where you felt pressure to soften him a little or make him more or less redeemable based on feedback you were getting?

HM: It was the strangest thing: When the book started to gel, I honestly just tried to keep up with him. I was working really instinctively—meaning I didn’t actually know what I was doing in my early drafts… I just knew it had to be a certain way. I knew he had to be challenging. I knew he had to be his own biggest problem. I knew he had to be the hero and the villain of his life… I just didn’t know why. I knew I wanted to write a book about America, but I knew I didn’t want to write a sermon from a pulpit. So when Akira started doing things, started talking shit, started messing up, I was surprised and figured I’d just see where it all went. When I started editing with Joshua Mohr—that’s when all the pieces started to make sense, and the larger themes came into focus. I don’t know how it goes for other writers, but if writing novels is always like that, I now truly understand why they seem like magic.

There was never talk of softening the character, only to work the reader more slowly into the sad, dumb truth of him in the hopes that it would give the book a better chance of getting an agent/selling in the more traditional route—which was excellent advice. And being excellent advice, you can understand why I wasn’t smart enough to take it! But seriously, Akira had to be what he is… that’s the whole point. No half measures. For the book to work right, softening him actually would weaken the overall effect.

BD: You’ve mentioned at least some part of this story and the character of Akira were based on your own mother getting cancer (and thankfully recovering) where you were playing that fun game of what might’ve happened to you if things had gone the other way.

Was there a thought process with you about him getting knocked on his ass a bit or getting “what was coming to him,” or finding “redemption”?

HM: He got into trouble all by himself—he didn’t need my help! As for redemption, I’d say that my job was to just try hang with him, put up with him, and just get him through this tough patch to see where he landed. As with people, I think I am probably hoping for the best, but anticipating the worst from everyone. That seems to be a safe way to operate. Everyone is the hero in the movie of their lives so, as the writer, you can’t really take sides with characters… You have to let everyone be who they are and trust that they’ll make the decisions they would as things go along. I think writers trying to steer the narrative are basically used-car salesman trying to trick everyone.

BD: Was there any sense of self-hate or self-preservation involved in who this kid was and what happened was going to come his way?

HM: Very little. My investment in Akira (or any character) wasn’t because he’s like me. I think, to write great characters, they all need to have something in them that you know and can relate to. Again—in their movie or their book, they’re the hero—so you have to be able to write each character from their own best point-of-view. Of the four main characters in the book, I have something in common with each… but of course none are me. My job was to understand each character’s point-of-view in all their scenes so they’d behave like themselves. The writer should not be in each scene awkwardly yanking on puppet strings toward specific results. Whatever the writer gets to say must exist solely and subtly between the lines.

BD: One of the things I love so much about this book is that from cover to cover it feels like such a punk-rock middle finger to so much of what many publishers, agents, and even writers might tell you your first novel needs to be these days.

HM: I’m taking that as a compliment. From my perspective, it’s a tough nut to crack because, sure, you want your work out there, in front of people… but it can feel like the only way to get it out there is by gutting it so it’s no longer your work, no longer your vision. It felt a bit like that for me. I tried the typical route for a bit… but it never really felt possible. And I asked myself, when all was said and done, what kind of book did I want on the shelf. For me the answer was the original book, as intended, free from compromise and done as well as I possibly could. Writer’s entire lives often constitute what—one inch, two inches, maybe five inches of space on the shelves of forever? We gotta do our very best to make it count.

BD: One of those expectations being the “single-narrative” expectations about what will sell or what readers will be able to wrap their heads around—readers who, as you say, often “lump the whole of Asia into a simplistic archetype… through either an exotic wonder or warfare.”

Was there ever a point where some very white asshole like me told you it was going to be “too confusing” to people to read a novel called Chinese Gucci about a Japanese-American kid named Akira from Albuquerque, New Mexico who loves rap and works his hustle crossing over to Juarez, Mexico to buy up knock-off high-end purses made in China?

HM: Not yet—but it might happen. Of course there’s not much reason in listening to someone like that. I think one of the reasons publishing can feel so bland these days is that it’s so often about profit margins and bottom lines that people are forced to listen to too many competing interests. When I think of classics like Catcher or like Tropic of Cancer, what would those meetings have sounded like? Those books never would’ve been printed. The downside of a big promotional machine is that all the people with skin in the game and their fear that they won’t get their goddamned money back. I’ve been publishing long enough to know that the only thing I’ve regretted is compromise. Doing the book myself meant no compromises were necessary. Having to listen to that very white asshole who thinks they get to say, “We have to change this” because they’ll get the book in Barnes and Noble, or reviewed at WhereTheFuckEver.com should be exactly the reason why NOT to listen!

BD: I know that the collage covers came later in the writing/revision process along with this idea of Akira as a kind of synecdoche for America, but were you having any of these conversations with yourself as you were writing this?

HM: I constantly thought about WWII while writing the book. Part of it was that Akira was Japanese… but also an American. Those associations are strong for me. Part of it was Catcher, and Salinger carrying chapters in his rucksack on D-Day. So that stuff was there all along. Like Akira himself, it was there and I wasn’t really sure why, but it just “felt right.” Later, when I realized I was writing about America—that’s when I figured out why it felt that way. Again—that part was magic. That part makes me wonder at the sheer potential of the human consciousness and subconsciousness… how somewhere deep down, this stew was being prepared and simmered and only after letting it cook for so long did it actually turn into something I could articulate.

BD: I know that you’ve said before that you knew that you wanted to write “the great American novel,” which by the way, I fucking love you so much for coming out and saying it no fuss, no muss.

Was there kind of a middle finger in your mind from the get-go—a desire to write “this great American novel” whether people wanted to hear it or not? Or was it more just: This sounds like a good fucking story I could turn into a novel that other people would want to read?

HM: My first goal was to finish the damn book! I always wanted to write “the great American novel,” and as I thought about this story, this book, I knew I wanted to flip the bird at the dull, and useless hyper-masculinity that seems to sprout like a cancer on the underbelly of American culture. I’m not smart enough to figure out where it all comes from—but I know what it felt like growing up, to have a natural instinct to be kinder or gentler, and culturally for that to be considered some kind of weakness. When you look at the things that always fuck with America’s collective mind: sex, death, desire, violence—none of these things are talked about in open or healthy ways. And the ways they ARE talked about… they’re tremendously unhealthy. To me, sex has always been a truly sacred thing… but say as much out loud, and the immediate cultural response, at least when I was growing up, was “What are you, gay or something?” So I definitely wanted to write a middle-finger to that kind of mindset, to the racist, sexist, misogynistic, jingoistic, truck-nuts mentality. The trick was to do it with a small, quiet, subtle story that people wanted to keep reading.

BD: Of course now that I’ve already asked you about all this, I’m starting to question if this whole line of questions about culture and race is revealing what a dipshit kind of white-guy douche I really am with my head up my ass, so I am sorry, and though I wish we could just pretend I didn’t ask what I just asked, I will also understand if you decide this whole line of questioning is so inanely fucked up and offensive that you stop responding to me completely, spam my emails, and block me from your twitter.

HM: Not at all. The fact that you worry about asking is evidence of how necessary it is to always ask ourselves this question: Am I just being an obtuse asshole? Usually the asking keeps that from every being the case! There are big things this country has gotten very wrong. Our only chance to sort things is by facing them, owning up, and trying to make it right. Like it or not, these questions are inextricably part of the American fabric. And, like Akira, I haven’t given up on us yet… but it’s obvious every day that we have a lot of soul searching and work to do before we’ll ever fulfill the promise of the American experiment.

BD: I was really interested in way you portray Akira’s masculinity in the book. You don’t give any easy outs for Akira or for the reader. There’s no built-in excuses or rationalizations for the way he talks/treats about women.

You lay out all these issues with his fucked-up ideas about sex and women and masculinity in this both subtle and in-your-face way that will probably make a lot of readers in 2019 (justifiably) uncomfortable but then don’t really offer any easy pop-psychology interpretations to rationalize it back to his parents or growing up in that stereotypical “tough guy” kind of world or really even as a nice, neat indictment of his culture/environment.

HM: I think that’s maybe the point. If there were easy answers to be had, wouldn’t we have things sorted by now? Wouldn’t we have had conversations about what this country has done to Native Americans, to African Americans, to women, to any and everyone but the old, white Colonialist men? I mean, if you’re writing a book about America, that book needs to be about America, doesn’t it? This pretending that everything’s okay, that we’re all hunky-dory here just doesn’t pass muster. Maybe it never has. So, when it comes to my work, and my books, and my little life lived in the transit of the 20th and 21st century America—I’m gonna do what I can to report it accurately, and spend time thinking about what kind of person I will be. We have to ask the questions—of ourselves, if not our cities, our states, and our country. I’m not saying I have answers. But I do have some of my answers.

As for Akira and masculinity: Everything about him screams “fake it ‘til you make it”—which people extol as some virtue and is, to me, terrible advice. Akira’s masculinity (and maybe America’s) is an imitation of what it is to be tough, to be strong, powerful. Maybe it’s born of necessity… because America is a violent and dangerous place, and carrying yourself a certain way means people won’t try you. But it’s exhausting. And dull. And not an especially inspired way of being in the world. Or moving humanity a little closer towards our next evolution. Yeah, we’re moving pretty slow culturally speaking.

BD: As white kid who grew up play basketball and football and listening to hip hop in the 90’s, then watching all the requisite shy, awkward man-child/manic-pixie-dream-girl comedies back then, I wonder if most readers twenty, thirty years ago would even pick up on all these things you are portraying about typical male posturing and puffery—which is to say, this was and is fucked up in how normalized it all was, or at least for a lot of men.

HM: It’s true. And it still is, in many ways. Culturally yucks came at another’s expense… and the more it hurt the funnier it was. “Normalized” is precisely the right word because at no point were we told to consider another way to be. We learned it little moments where, after shooting off our mouths, we’d seem a glimmer of pain in someone’s eyes and unless you asked yourself what that was about, the lesson was lost.

There’s another side to hip-hop, in that it very obviously was selling escapism and fantasy as a means of surviving true, daily, existential dread of African-American life. And until future centuries bring much more parity, I’m not gonna talk shit about it. Like Bukowski said: digging through the cement walls with a bent spoon keeps the heart alive. So until there are no walls, I say keep digging.

BD: Did you have a clear vision of what you wanted to say about masculinity in here from the get-go? Or was that something that just naturally evolved with the character and/or with your own experiences growing up?

HM: The only thing I wanted was for it to be a true reflection of the kind of American masculinity I see as a huge part of our cultural problems. I figured the truth of it was enough. As there’s no way to control what a book will say to different readers, the part I could control was the accurate re-telling.

BD: It’s been a couple months since you put out Chinese Gucci. I was wondering how the post-publishing experience has been since its been birthed out into the world?

HM: I set what I felt were some humble yet realistic goals for myself and the book—selling all the special editions, getting copies in a few stores and libraries—and most have happened, so I’m really happy. I’m lucky that I have a really terrific group of family, friends and folks who follow my work, and buy collectible editions, and often drop me a quick note when they’ve finished a book—and it all definitely keeps me going. They’re the best.

BD: With this being your baby, do you feel more pressure/stress/anxiety/recurring feelings of inadequacy about having to push it yourself, having to put yourself out there more on social media since it seems like you’re not someone who loves social media to begin with?

HM: I don’t mind social media, though I truly don’t feel especially “good” at it. Hot takes, beefs and clapbacks—I don’t know, maybe that ship has passed me by. A big part of me is introverted, and I don’t know where a comfortable line is between public and private stuff. It’s tiring for me to try to find it, so I tend not to do that much. As for pressure or anxiety to push the book: It’s true that it’s tough to reach new readers—there’s just so much happening all the time. I see people launch books daily, and I’m not even that deep into social media. I’m not a great hustler of things, as I really don’t ever want to twist anybody’s arm into buying my books. Measure that against feeling very proud of the books I have out there, and really wanting folks to take a chance on them…and, again, it feels like being caught between a confusing rock-and-a-hard-place. To me, the hustle is the hardest part of writing. I absolutely want people to read my books… but I never want to push anyone into it.

BD: I guess I’m wondering how publishing the book you wanted to publish the way you wanted to publish it then translates to promoting the book the way you want to promote it?

HM: I suppose my default setting when trying to figure out how to spread the word about a new book is by asking myself: what I respond to, what would I like to see someone doing… then I just try to copy that vision. The down side, of course, is I’m not necessarily the best judge of what “works”—if anything ever does. It feels like trying to read tea leaves, or conjure spirits—it’s all a confounding mystery to me. So I guess I just do my best. I’m not especially tech-savvy, so I give myself a long time to work on things and try to get them right. I have been working with Ben Tanzer—as he is much better at this side of things than I am. He’s been really terrific.

BD: Do you imagine you would’ve had to’ve put in more hustle or less hustle if you’d had a big press to push it with you (but probably make you do a bunch of stuff along the way to “sell” yourself)?

HM: It would only be more with a big press because I think that’s what big presses have over small ones—access to a larger promotional machine. It would be more hustle with a big press because they’d probably have more things for their writers to do. And if that was my reality, then I’d do my best. With the small press though I do think there’s a bit more freedom, and more you can do or try. Does it work any better? I doubt it—but it is a lot more fun. I remember on the THIRST blog tour I played a drinking trivia game with Russ Litten in the UK, kept track of everything we drank over a weekend with William Boyle, talked tacos with Lori Jakiela. That bigger promotion machine is mainly built on reviews in larger venues, sometimes an interview in a national magazine. I’m sure those are fun too, but the small press can and should try to do drastically different things. At least that’s my $0.02!