First disclaimer: I’m usually suspicious of writers with “range.” I distrust writers who can write in different genres and styles. Darrin Doyle’s got range. I’m suspicious of Darrin Doyle and his range.

Sure, Doyle writes mostly fiction—short stories and novels—but his fiction is the literary equivalent of that decathlete guy Dan from those old Reebok commercials with that other guy Dave who, unlike Dan, ended up kind of sucking in the Olympics.

Second disclaimer: I’m mostly a one-trick pony. As a writer, as a storyteller, as a person. My jokes get old. My obsessions get annoying. My tics get obnoxious. My stories all beat the same dead horses. I’ve been told recently and many many other times throughout my life that I need to get out of my “comfort zone.”

I distrust people who tell other people to get out of their comfort zones.

What I mean to say is I’m insecure as a man and a writer. Often petty. I usually hold it against writers like Darrin Doyle—all their goddamn “range.”

When I’m holding it against them, I often cite other famous writers who were, for better or worse, famously one-trick ponies. I would list some of my favorites here to support my bias, but then we would probably get caught up arguing about the greatness or the over-rated’ness of said one-trick-pony writers.

Which I would take personally.

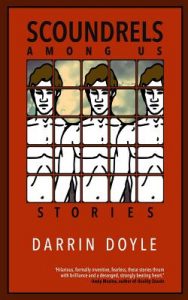

And pretty soon I’d completely forget that this is supposed to be about Darrin Doyle’s range (See also: his two previous novels The Girl Who Ate Kalamazoo and Revenge of the Teacher’s Pet and his two recent short story collections The Dark Will End the Dark and Scoundrels Among Us).

The range and dexterity in Darrin Doyle’s latest (Scoundrels out October 2 from Tortoise Books) makes me want to pick holes in it. It makes me want to tell you that it’s inconsistent, maybe a little all over the place.

It is not. Which is kind of bullshit.

Or, rather, it is inconsistent and all over the place, but in this beautiful genius dissociative disorder kind of way—but as if all the different personalities were your least obnoxious friends hanging out at the same party riffing on each other’s stories all night like a bunch of your favorite comedians competing for laughs backstage at a benefit for a disease that’s been around for so long and taken so many lives that we have to keep holding nationally televised benefits to remind ourselves that we haven’t cured it yet.

I feel like that might’ve been a mixed metaphor. I don’t know Darrin personally, but I feel like he would forgive me for mixing my metaphors.

Of course, Darrin Doyle does not mix his metaphors. His metaphors have real range, but they always punch you in the nuts in a way that you feel the jolt immediately, but then you feel something more intense a moment or two later when the tingly ache spreads.

The pettiness in me wishes I could tell you that Scoundrels Among Us falls far short of its lofty ambitions. My insecurity makes me wish I could tell you that in his latest book Doyle’s bitten off more than he could chew.

But I cannot. Because it does not.

There’s a story about identical nonuplets who all live and work in a Wal-Mart-lite Superstore and date the same girl. There’s a story about a random dude floating in the sky and the countdown to WWIII that ensues in the city down below. There’s a story with a guy named See You Next Tuesday (spell it out in your head) which is probably the one of the oddest mixes of tenderness, crudeness, and violence I’ve come across in a story.

There’s a story about a young boy feeding the ducks and how this kid will probably end up an abuser or at least a bully of the worst kind. There’s a story in the form of a review of a book called Cold Blood from a Scorched Cat: Sweet Whiskers in the Grip of Death. There’s a series of semi-connected stories in the form of seemingly random Q & A sessions that act as the connective tissue throughout the collection.

Like Alanis Morrissette, I’m pretty sure I don’t fully understand irony, but I still feel the irony in all of this. The randomness that connects it all. The questions that don’t get answered, the answers that don’t answer the questions. All the scoundrels popping up where we least expect them.

And voila: Here I am listing random story plots from throughout the collection and trying to convince you I have range, too. Look at me getting out of my comfort zone, Ma!

If I were less insecure, less petty—if I were a bigger man than the 320 pounds I already I am—I would tell you that the real connective tissue, the actual star of the show, is not even the “range.” It’s Doyle’s ability to write a line. And then write another line and then another and have all this pull you through and punch you in the nuts and then keep pulling you through to find out what happens next even if it’s going to be another punch to the nuts.

And obviously, it’s not the same voice; it’s never the same voice. Same way it’s never quite the same song, never the same notes. That would be too easy. Too predictable.

Captain Obvious says Scoundrels Among Us is not predictable, it is not easy.

And maybe that’s what pisses me off most about Doyle’s collection: He makes it seem so goddamn easy. As if he’s making all these stories up on the fly but never tells a dud, never has misses a line, never an ending that falls flat. He knows when to pull, when to punch. He knows when to get ugly, when to get tender. I’m want to write clichés here about boxing and jazz music, but for the sake of Darrin Doyle, I will not.

Instead, this one: He’s like a comedian who never tells the same joke two nights in a row. And kills every time no matter what the audience is looking for. I wish I could tell you how to heckle him. I wish I could tell you what the punch lines are going to be.

And then to top all this other shit, he’s pretty much the smartest, most articulate, down-to-earth, and likable authors I’ve ever spoken to. Which now makes me feel like a real asshole and hack for everything I’ve just written.

Last disclaimer: however you feel about what fiction should do and what fiction should be, you need to read Scoundrels. You need to read Darrin Doyle. His world vision, his heart, his ability to cut to the core of what makes humanity tic, what makes humanity ugly, what makes humanity beautiful–it all should be required reading for everybody.

Think I’m blowing smoke? Just check out this interview. Then go out there and check out his fiction.

– Benjamin Drevlow

BD: I’m always really curious about the process that goes into putting together a cohesive collection of short stories. It’s definitely an insecurity of mine, this unhealthy idea that if you want to be a “real” writer, you should be writing novels—big novels. And of course, I’ve tried writing those and maybe one day I’ll publish one, but at the same time, I’ve probably been more influenced by story collections than all the novels I’ve read—big or small. Probably the two biggest influences were Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son and Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried—books that work both on an individual level and as a sum that is larger than its parts.

But then both of these are connected collections that already read like novels-in-stories. What about a collection like Scoundrels with stories that bounce all over the spectrum of realism and realism-adjacent?

I think I read somewhere that you’ve had trouble in the past with collections that editors thought weren’t cohesive enough because of this range in your stories.

You’ve written and published multiple novels and short story collections; do you have an ars prosetica for how story collections should work (versus novels) and what they should accomplish?

Or at least what you’re trying to accomplish when you are deciding what to include and what order they go in and such?

(My apologies: as in your book I admit I sometimes “have difficulty differentiating between questions and statements.”)

DD: I hate that pressure of believing that the “big novel” is the only way to show that you’re a “real” writer. I’ve felt it, too. You’re right that it’s unhealthy—quit it! Seriously, though, it’s hard not to feel that way when that’s what is held in front of us as the standard for canonical, lasting fiction. Year after year, the commercial publishing houses and major literary awards sanction those kinds of novels as the stuff that we should be paying attention to. (Don’t get me started on how humorous fiction gets the short shrift.)

I’m glad you amended your opening paragraph to point out the difference between Scoundrels and the Tim O’Brien and Denis Johnson collections. With a single protagonist running through both of those books, they’re really novels in disguise. Don’t get me wrong: those books are among my all-time favorites (I was also lucky enough to meet and hang out with both of those guys!) but a reader probably won’t have their names pop into mind while reading Scoundrels.

My collection is more indebted to the early postmodernists: Donald Barthelme and Robert Coover; contemporary innovative authors like Noy Holland, Christine Schutt, Kelcey Parker, and Kathryn Davis; humorists like Barry Hannah, Charles Portis, Gary Lutz; and classic short story writers like Shirley Jackson, Kurt Vonnegut, and John Cheever.

It’s true that I never like to write the same thing twice. To give a cliché analogy, I’m a Beatles White Album guy; a Pink Floyd Ummagumma guy. Albums stylistically all over the map; and I dig that range. I favor movie directors like David Cronenberg and P.T. Anderson. Percival Everett is an author I’ve read for years, in awe of his different styles. That’s the kind of author I find myself being—not because I set out to be that way. Over the years I’ve just learned that that’s who I am. I’m impatient. My own writing can bore me easily, so I have to keep surprising myself.

I do think that in today’s commercial fiction market, a stylistic range is not considered a marketable thing. I had a literary agent for my first novel, which she loved. My second novel, however, “scared” her. So we parted ways. I got a different agent for my second novel, which sold to St. Martin’s. But the next two novels I wrote did not sell, and I parted ways with that agent. When I look at some of my favorite recent authors who find consistent “success” (as defined by commercial publishing), I realize that they more or less write the same kind of book again and again. There’s definitely something to be said for a writer who “finds their voice” and hones it. I admire that, actually; but it’s not me. It’s like the band AC/DC. I fricking love them, but they basically do the same song about five different ways. They’re genius at what they do, but as an artist I can’t stay within a range like that.

As far as how to assemble a story collection. . . I wish I had an answer. Truly I am a simpleton when it comes to putting things in an order. It’s similar to music, to making an album: you don’t want a bunch of slow songs in a row; you probably don’t want to open the album with a nine-minute instrumental (unless all the songs are like that); you want to open with something that represents the overarching theme or style of the collection; you want there to be a sense of varied rhythm and movement, emotionally, throughout the course of the experience.

For a collection with 29 stories (like Scoundrels), I more or less threw them at the wall to see what stuck. I loosely arranged the order around the four “Session” stories, which helped me to break the book into quarters. My editor Gerald Brennan at Tortoise Books was also excellent about deciding which ones to leave out (there were about four other stories in there originally) and what order to put them in.

By the way, thank you for the phrase “realism-adjacent.” I’ll be using that from now on!

BD: One of the things that I really admired about Scoundrels was the lyricism of it in collaboration with the elements of surrealism. You have an awesome ability to set up an odd or surreal premise and pull the reader along with a kind of fairytale-ish rhythm and voice.

I’m thinking of stories ranging from “Insert Name” (theoretically plausible but weird) to “Dangling Joe” (with a guy magically dangling in the sky) to even the brutality and perversity of the titular story.

It almost felt like the “yes and…” approach to improv comedy where one line would set up the premise and then the next line would expand on it as if it were nothing out of the ordinary (almost like the lyrics to a surreal song that never seem to make sense but you’re singing them anyway).

My question: How much of the realism/surrealism/oddities of your writing are planned out ahead of time versus the happy little accidents that happen when you’re flowing from one line to the next?

How do you walk the balance of when to say “yes and…” versus when you say, “yes and… that was pretty stupid and makes no sense and ruins everything”?

DD: I love the analogy to improv comedy. When I write I do feel like I’m improvising, playing one line off of the next, listening to the meter and cadence of each line and using that to help dictate the next line, finding my way blindly in the dark and searching for a laugh.

I actually began answering these questions in reverse order (I seem to do this in my life a lot; working backwards or “out of order”; maybe it’s because I’m half-left-handed?)

Anyway, my answer to your next question addresses how much I plan ahead. To give a preview of that answer, I rarely plan anything. I begin with a line, a conflict, a voice, a concept. And then I run with it. Sometimes it works and results in a solid, complete story; sometimes it fizzles out.

For example, in “The Search for Boyle” I picked the title first. The name Boyle just stood out to me (I know a guy with that last name, but it’s not based on him; it also sounds a lot like Doyle, although that wasn’t a conscious realization until later). The opening sentence came very easily: “Five workdays and two weekends had passed and none of us had seen Boyle.” Embedded in that sentence is the first-person plural POV, and I soon after imagined these factory worker guys who bust into a coworker’s house because they haven’t seen him in a while. That situation seemed funny to me. Line by line I like to surprise myself, so instead of saying “they hadn’t seen him around walking his dog,” I decided to have him walking his cat.

(An aside: One of my former students would take her cat for walks on a leash. She also brushed its teeth. I always thought this sounded strange, but whatever floats your boat. Then I remembered one night meeting a young woman who was walking a hybrid African cat on a leash; this cat was exactly like the one I ended up describing in the story.)

To continue: when I was college-age my friend (we’ll call him Pat) and I were at some guy’s house (we’ll call him Blump) trying to buy drugs. Blump wasn’t a friend but was sort of a friend-of-a-friend. Anyway, somehow me and Pat ended up sitting around alone in this guy’s apartment for a few hours, waiting for Blump to come back with the drugs. We were pretty high and looking around at his stuff, and I’ll never forget the freezer with just a half-empty box of fish sticks, and that bedroom with the single mattress, the bare light bulb, and that caseless trumpet standing on its bell in the corner. That trumpet was the weirdest detail. This guy Blump was not a musician-type. Why did he have that trumpet? Those images have stuck with me for the past twenty years, and I’m glad I got to put them into a story. From there, the story turns into a kind of Twilight Zone meets Sartre exercise in existentialism.

That’s just an example of how a story might evolve. But you’re exactly correct that sometimes you have to cut the stupid stuff, the gratuitous stuff. Anything that feels too self-aware or clever gets cut. As Raymond Carver wrote in his essay “On Writing,” I’m attempting to capture my own “unique and exact way of looking at things” while being constantly aware of Carver’s warning: “Too often ‘experimentation’ is a license to be careless, silly or imitative in the writing. Even worse, a license to try to brutalize or alienate the reader.”

But how to recognize it as silly or careless? I’m not sure I can articulate it.

Like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said when asked how do you know when something is pornography: “I know it when I see it.”

Or at least I hope I do.

BD: In a number of stories in Scoundrels, you seem to be exploring the ugly, complicated, and often corrupting influence of our cultural and personal expectations of men and masculinity—with the self-destructive behavior of men themselves as well as the other men and women around them.

I was thinking about the boy in “Water Fowl,” Ron Borman in “The Engagement,” Bernie as well as the town’s suspicions of Bernie as a kidnapper and pedophile in “Slice of Moon,” and probably most directly in the C-word-named character from the title story.

The book’s titled Scoundrels Among Us, which doesn’t necessarily mean men, but I think most people have pretty strong male connotations when it comes to “scoundrels.”

Without naming names or getting overtly political here, it hasn’t been a banner few years for a lot of wealthy, famous, and highly influential men (in the literary world, the celebrity world, the sports world, the political world, etc.).

Were you consciously writing a series of stories examining masculinity? Maybe responding to some of these scandals and the corresponding social debates? Or was it more that as a man, you were simply interested in the things that men do to themselves and others?

(Or option D. I’m just reading way too much into this because I run a magazine dedicated to exploring issues with masculinity.)

DD: The short answer is no, I wasn’t consciously writing a series of stories examining masculinity.

But the more interesting, more accurate answer is yes, I was unconsciously writing a series of stories examining masculinity.

I’m a huge believer in trusting the unconscious. Notice that I said “unconscious” and not “subconscious.” These terms are often used synonymously, but they’re not the same. In the original psychoanalytical sense the subconscious is something below our immediate awareness but still accessible with a little effort. Unconscious literally means that it isn’t accessible because we are completely unaware of it; it’s essentially what is called an “unknown known” (Slavoj Zizek used this to describe things that we know but are unaware of knowing).

So when artists create, I think they should trust their unconscious directives—from word choice to sentence structure, voice, decisions about plot, character, and setting, etc. In other words, go with your gut. Don’t worry about why you’re doing something (especially in a first or second draft; those later conscious decisions are essential, but use them to shape what your unconscious has already put down) because in my opinion there is a reason you’re doing it: you just can’t know the reason. And you have to be comfortable with that not-knowing.

Story collections form gradually, over a long period of time. They are written in isolation from each other and only come together to be neighbors after they are full-grown.

However, I did write many of these stories between the summers of 2015 and 2017. And as you said, that stretch of time wasn’t a banner period for good male behavior. The Republican primaries were the backdrop of my process, and Mister Pee Tape was blabbing his fat mouth around the clock. I’m pretty sure he was in my head when I wrote “Scoundrels Among Us.” And “Water Fowl” was written three or four months after the election; that one was definitely my attempt to grapple with some of the toxic masculinity we’d been seeing.

Having said that, if I look back through my entire life, I’ve always been aware that men are creeps. We’re violent. We’re petty and selfish and entitled. I’ve seen my share of bullying, and as a kid I was constantly in fear of getting my ass kicked.

With regard to men’s behavior toward women, it’s bad. So many times I have known a dude, hung out with said dude, thought said dude was cool and friendly and a “good guy” only to hear from some young woman friend about how he grabbed her ass or said such-and-such horrible thing over social media or did something else just plain wrong.

I believe that the majority of men (myself included) can never truly grasp how badly men behave toward women on a daily basis. The #MeToo movement is a good start at raising awareness, but it’s really only pointing out the most egregious behavior of famous men when what we need is an entire cultural re-positioning that puts women and men on an equal playing field from Day One. Even our language is mined with sexism, phrases like boys will be boys and man up and grow a pair and crying like a little girl. These bother me to no end. I’m not comfortable, for example, referring to a group of men and women as “guys.” But many young women are comfortable with this. Anyway, it’s not something that’s going to change overnight.

BD: Full disclosure: I go to a therapist. I am also a bit of a self-talker (I spend a lot of nights and mornings reenacting conversations from the previous day where I try to sound less like a dithering idiot).

This latter confession is probably my single biggest motivation to write: to put the voices in my head down on paper… to reimagine the narratives of our conversations.

My therapist says I really need to work on less negative self-talk.

My wife says I really need to get better at listening to her and not just jumping around to the imagined talking points that are always looping around in my head.

The point being, I really loved the Q & A sessions that stitched this whole thing together. The last one about the privileged white guy is still fucking with my head as I write this.

Maybe not the actual conversations in the book, but how much of this was shaped by your own mental calisthenics?

Feel free to disclose or not disclose your deepest, most fucked up thoughts and/or confessions to the therapist you may or may not see yourself.

DD: I’m glad and flattered that you enjoyed the “Sessions” stories. I had a lot of fun writing those, in part because the whole format was so freeing. I could de-emphasize plot, conflict, setting, and character development. Like a poem, I could leap wildly from one thought or concept to the next. Whatever ridiculous question or answer popped into my head, I could write it down.

Having said that, this freedom and boundlessness was also a little intimidating. It meant I had to really turn up my own BS detector and not just have the conversation be lamely self-indulgent. I ended up writing a few other “sessions” that didn’t go anywhere, and I trimmed the ones in the book extensively, trying to give them some shape and concision.

So as a way of getting around to answering your question(s), yes, these were very shaped by my own mental calisthenics. They were also influenced by David Foster Wallace’s “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men” and Joseph Bates’ “Gashead Tells All” (among other interview stories).

What I found is that both the Questioner and the Answerer developed their own personalities and voices. Undoubtedly they are both components of myself, but they’re also exaggerated and fictional. What I will happily share with you is that I often wonder some of what the Answerer wonders, which includes the questions 1) Why is it that I feel like an outsider when statistically from a socio-economic/market research perspective I should feel like the most “welcomed” person in the world?; and 2) Why does happiness always have a price?; and 3) What is the purpose and benefit of social interaction?

Much of what the Answerer muses upon comes from my “real life,” such as the fact that I lived in Manhattan, Kansas, and the wind was really fricking powerful. But unlike the Answerer, I never squatted inside a family home for six months or walked backwards down the streets. Maybe part of me would like to?

Overall, these stories gave me the opportunity to raise questions. On the other hand, I believe that all good fiction and poetry (and art) raises big questions, so it’s not exclusive to this particular form. This form probably just let me articulate the questions more directly.

And as far as fucked-up confessions, I have to say that I’ve already made those confessions: they’re in the book (and in my other books). You’ll just have to figure out where they are.

BD: I see that you aren’t going to admit to any dead bodies you might’ve buried in dunes of West Michigan. I guess we’ll leave that to forensic literary critics of the future.

How about this: I remember hearing some author once saying that part of maturing as a writer is learning to accept that the book that you end up writing will never be the book that you set out to write.

I struggle with that a lot, myself. I’ve got all these Big Grand Ideas and I tell myself this next book is going to blow everything else I’ve written out of the water. This is going to CHANGE PEOPLE’S LIVES!

Then of course later when that doesn’t happen, I tell myself I’m a complete hack, a poseur, and I should just quit and be a janitor somewhere.

I also think about this managing of expectations a lot in regard to the ideas of what kind of writer I thought I wanted to be when I was younger and then eventually coming to terms with (taking pride in) the type of writer we become twenty or thirty years down the road.

You seem to be pretty well adjusted and to have a healthy sense of identity as a writer. You’ve mentioned a few times where you’ve changed agents over the years and had books that didn’t sell. Did you ever have moments where you questioned the way you wrote or the types of things you were writing?

You’ve also mentioned that you try to never write the same story twice. Do you ever reread older stories or books you’ve published and think, “Christ, what the hell was I thinking?” Do you ever have arguments with five-years-ago Darrin? Twenty-years-ago Darrin?

Feel free to just answer this long rambling navel-gazing question with a simple. “No.” Or maybe the semi-extended, “No, I’m an Actual Writer, but it sounds like you need a lot of help and maybe a hug.”

DD: I’m pretty sure that anyone who pretentiously labels themselves an Actual Writer probably is not an actual writer. What I mean is that I’d be surprised to find anyone who busts their asses day after day in isolation, living inside their heads, making up shit, monkeying with words and sentences for no clear reason, for little to no reward (or god forbid, payment)—I would be surprised to find anyone like this who doesn’t experience serious self-doubt on a regular basis.

I’ve always been a pretty confident person, confident in my abilities. I work hard and have a strong sense of discipline and work ethic. But if anything can humble a person, it’s the process of trying to “make it” as an artist; to devote your life to creating a thing that has no tangible, measurable purpose in our particular culture. Why the hell should anybody care about my stories? Over the years I’ve been rejected thousands of times, literally thousands. That’s part of the game, simple as that. Whether it’s music or film or dance or visual arts or writing, art is a horribly difficult area to find success in, and even the very definition of “success” is so nebulous and subjective that it can drive you insane. How can you tell when you’ve “made it”? You can absolutely murder yourself by measuring your worth against other people’s successes—a miserable, debilitating waste of time. Yet we all do it.

So obviously yes, I suffer from the self-doubt you describe. It’s a matter of not letting it become the loudest voice in the room. To me, nothing feels better than simply sitting down and actually writing rather than thinking about writing or thinking about my identity as a writer or my success as a writer or any of that other nonsense. Because none of that matters. All that matters is putting words on the page. All that matters is to have a compulsion toward this craft. Work hard, trust yourself, read, read, read. I get deep fulfillment from reading literature, from creating characters, from writing sentences, from pondering questions about human nature, blah blah blah. The means is what it’s all about. The end result is less important.

I’ve found that as soon as I try to write something to please someone else or to fit into a particular category (i.e., to be more “marketable”), these are the times when I struggle. The two novels that failed to find homes were written (at least in part) with a certain audience in mind, and probably that’s why they’re still in my desk rather than out in the world. I poured so much work into those books, so much mental and emotional energy, and at the time it was devastating to think they would be shelved. But in retrospect I wonder if my writing process was tainted from the start, trying to be someone that I’m not; making assumptions about audience rather than just being myself; trying to cram my voice, my worldview, whatever, into a mold where it doesn’t quite fit. Maybe those novels represent a vision that isn’t entirely my own—I could be overreacting, but that’s how it feels sometimes.

Fortunately I’ve never looked back on my published work and said, “What the hell were you thinking?” All of the published stuff went through so many revisions and edits that I’m proud of all of them (at this point—you might get a different answer in ten years). Not that I re-read much of my published work anyway, because that feels kind of pointless to me.

However, I have MANY unpublished stories that make me feel silly, embarrassed, confused, and all sorts of other unpleasant emotions. At the same time, those stories were not mistakes. Even if I think they’re awful now, they aren’t failed stories; they’re simply not complete; they were abandoned, but they served a purpose in my development.

With my students I like to use sports metaphors, so I equate so-called failed stories with practices or scrimmages. Does a pro volleyball player look back on a bad performance during practice and let that define her? Or even a bad game? Even Tom Brady has games where he throws four interceptions. Who cares. You just keep going and try to learn from it. It sounds corny, but I believe there are no failures; there are only experiences.