Your entire life was pretending, making everyone believe that everything was fine.

– Nicole Tallman, “The Last Moments Leading Up to Your Death”

Fernando’s brother, Richie, had been out of jail for a few months. He had to join some recovery program or something, a place where someone with a shitton of their own baggage and maybe a BA in psychology will tell a guy like Richie, “I think you should confront your brother. You’ll never move past what he did to you.”

I come to see Fernando and his husband, Gregg, every time I make it out to Chicago. They always know the best spots, like this swanky place at Restoration Hardware on Dearborn. He’s on his third cocktail and I am trying to get the details, but we sat right next to this fountain (under an enormous chandelier… very Chicago). I only hear gun, “Did you say he brought a gun?”

“Yes, the motherfucker!” a couple of patrons look our way but Fernando stares them down. “My brother came out here to murder me, J.D.!” Gregg pops an olive in his mouth and nods at me.

Nineteen years in jail (for putting a gun to a man’s head), a lifetime of brotherly trips to California and back home to New York. And one night, surrounded by everyone who only knows his side of the story, the way he tells it, who maybe see themselves, see all the mothers and fathers and Fernandos of their own stories, the people who really deserve the blame. I heard these groups tell you that you have to own your shit, but I’ve never met a person with a chip who didn’t have a big damn list of names they’d rather blame it all on.

“He called me a sociopath!” he tries to rise above it, but anyone can see it still stings all these months later, “I told that sonofabitch I bet he couldn’t define it.”

When I used to talk to my brother, Sam, he’d usually call drunk, “Hey, little brother.”

“Where are you staying?” It was usually on the street, but sometimes an old friend would offer his couch and a shower.

“Oh, I’m back at the hospital cause of my diabetes,” hospitals in Long Beach can’t turn away the homeless, “Hey, hey…” he’s not talking to me, some poor nurse, “Hey, I asked for another ice cream because I don’t like chocolate. Can you get that for me?” Decades on the street and he still treats doctors and nurses and just about everyone like they’re “the help” (and we grew up poorer than anyone with actual jobs like “the help”).

I can’t help myself, “How did they let you stay there drunk?”

Unconvincing, “Brother, I’m not drunk.”

“Okay. What’s up? I’ve got to get to bed soon,” anything to give these calls a time limit.

Impersonating me, extra lisp, “Oh, excuse me! I didn’t mean to bother you, little brother. I didn’t realize I was bothering you and your busy life, little brother. You’re a stuck-up little faggot, you know that?”

When he went back to jail (for fighting with a cop), he wrote me these long letters apologizing for things he said. Half of it I couldn’t remember, the other half was probably for one of our other brothers—but he had my address. Who knows why I sent him the care packages. I told my twin brother, Joseph, “It’s an investment. Every package is a phone call I don’t have to pick up.”

Fernando tells me about therapy. We’re back at their place overlooking the lake. It’s a gorgeous night, lights on the water, little ripples. Gregg brings us both a glass of whiskey. “Do you know, J.D., Richie and Lenny both asked me why I left them behind?”

First-generation Columbians, meaning whomever you came over with you were stuck with. Which is why his mom didn’t leave the husband who beat her, still kept in contact with the uncle who molested her oldest son. People will use the word family to tie you down, to tie you to them. Forever if they can. So, Fernando left as soon as he turned 18 and never looked back.

He takes two big gulps, “What the fuck was I supposed to do?” He’s gonna be 56 in a couple of months, but a couple of texts from his bored brothers and he’s back there. The lake looks endless.

My sister spent most of my life apologizing for leaving me and Joseph behind. I never really understood the need for her to apologize. Except I’d sometimes hear my older brothers griping, “Yvonne thinks she’s too damn good! She’s a stuck-up little bitch!” Like them, the catchphrases and vocabulary remained stunted. Well, I always wanted to be like my sister.

I ask Fernando what happened, if they are talking at all. He smiles, “Oh, you’ll love this” and Gregg cozies up on the couch, he’s smiling, too, “That little prick calls me on Christmas and is like ‘Hey, I was going through some stuff’ or some shit. Can. You. Believe. It?”

“Girl, it’s always like that,” I think of Sam’s jail letters, or how he came crying when he busted the living room window and said he was going to kill me when I wouldn’t open the door because he was drunk. “So, what did you say?”

“I said he could fuck off,” Gregg gives a little clap for his husband and Fernando smiles.

I was a fat, awkward, lonely kid, and in third grade, I had this teacher who was kind to me for seemingly no reason. She knew I liked animals, and she’d give me all of these old animal magazines and let me cut out the giraffes and zebras instead of sitting by myself on the playground. I came home one day and told my mom, “Mrs. Wallace has this giant house full of animals, and I got to see them all.”

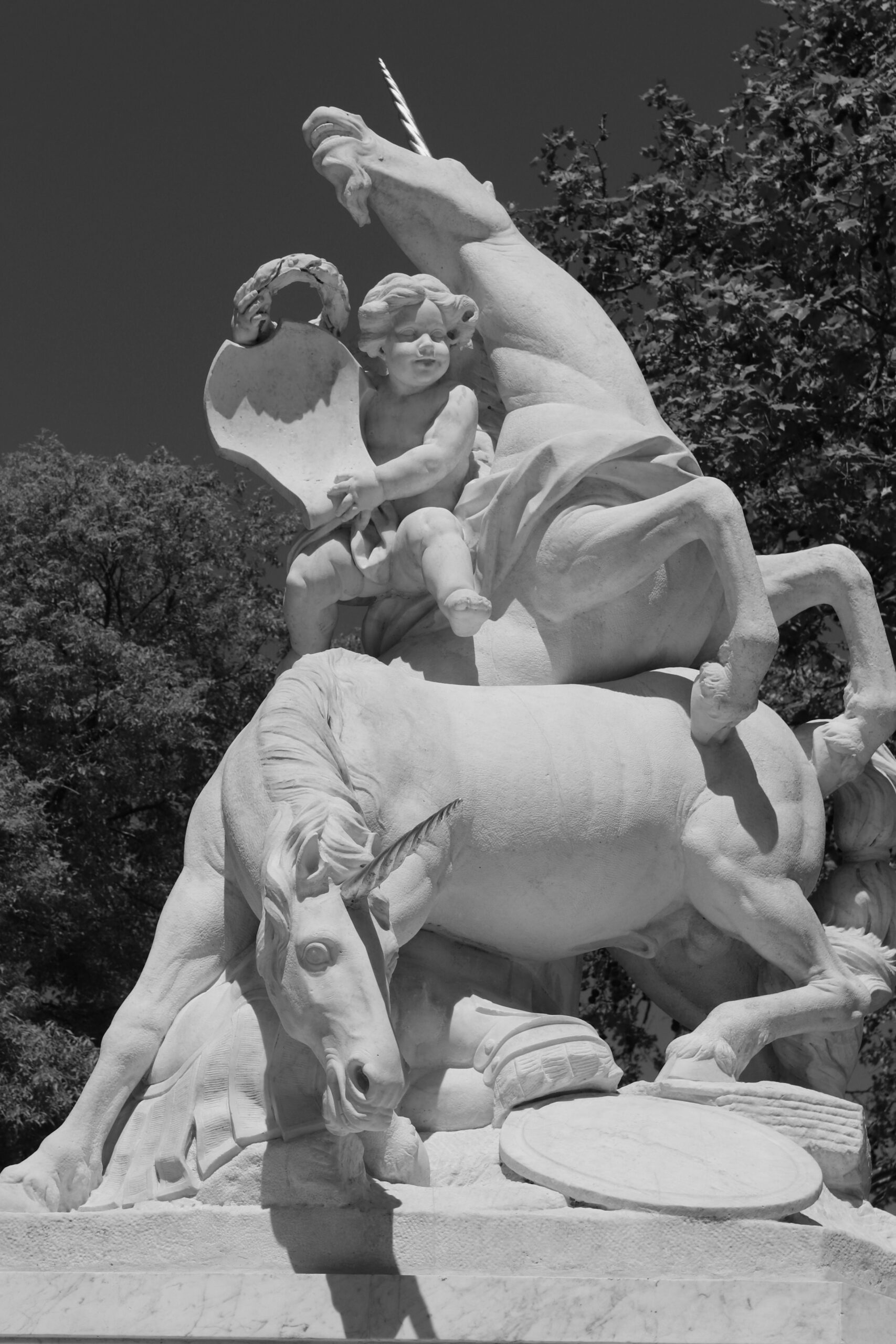

And my mom said, “Did she have rhinos and unicorns?” because my mom lived a life you had to make up to survive.

And I said, “Yes! Of course, she had unicorns” because, even then, I was learning my own survival skills.

When I hug them goodbye, Fernando says, “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to dump all of my family baggage on you on your vacation!”

“I enjoyed every dramatic detail,” Gregg and Fernando laugh as I kiss them, give another hug.

“Well, I want you to know I am over it. They can all go fuck themselves!”

Yes, of course, there are unicorns, my friend.