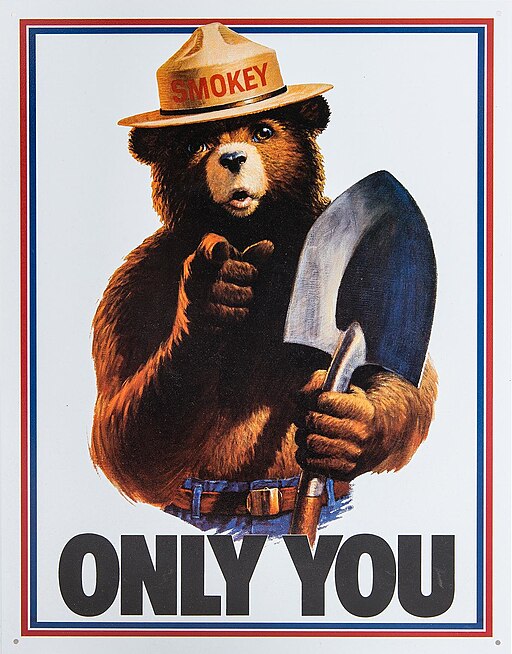

Only You Can Prevent Wildfires

Nearly nine out of ten wildfires are preventable. So, douse your campfire until it’s cold. Keep sparks away from dry vegetation. Hey, I’m talking to you. Get off Instagram and listen up. You think you’re better than me? A guy in a bear costume with a ranger hat and hollow eyes. You think because you live in New Jersey you won’t be affected by micro-particles floating south from fires in Canada? Have you seen the inside of your lungs lately? No, I’m just messing with you. It’s cool, really. I know, I know. You’ve heard it all before: dry weather high winds climate change human carelessness blah blah blah. I feel you. Fun fact though: in California, 10,000 giant sequoias have died. Deforestation is up 40 percent in Washington State, That’s a lot of dead hemlocks. Not to mention the moose. They smell godawful when their flesh burns. Makes a sizzling noise, like moose on a grill. Makes me want to go home, rip my head off and grab a Bud Light. You think you’re tired? Having to repeat this shit while wearing a scratchy costume is exhausting. Want to know a secret? I’m quiet quitting, biding my time till retirement kicks in and I can go on Medicare. Saving up for a condo on the beach. Know what else? In Maui, right before buildings collapsed and all those people died, the sky turned this incredible flamingo pink color and it was so gorgeous, it made me cry.

How to Bury a Word

Beat (n). A regular, repeating pulse underlying a musical pattern. Also to strike (a person or animal) with blows of the hand or any weapon so as to give pain. When spoken aloud, synonymous with beet, a succulent root vegetable used for food that yields sugar.

First, decide on the method. Best to take the “b” and “t” and wrap them around “ea,” squeezing tightly. A quick, clean death.

Next, hide the evidence by focusing on something else. The dishes. The weather. The past—in better weather. Daffodils and Snickers Bars. Chardonnay dreams. Fingers uncurled, soft as newborn kittens.

When the police arrive, wagging their beet-stained tongues, say nothing that would incriminate anyone.

At the funeral, shroud the word in unreliable memories: An argument. A bed. A fist. Something torn. An eye that refuses to open. All soaked in his vodka regret.

Sob into your hankie without shedding a tear.

Invite seclusion, confusion, and illusion to give the eulogy.

Sprinkle violets and euphemisms on the coffin. For instance, spin the truth. Instead of lie.

Replace with alternate words. Not synonyms like batter, thump, punch, thrash, maul, smack. Softer sounds: pat, touch, dab, pat, stroke. Convince yourself these are not the same thing.

As you leave the cemetery, passing headstones of words you’ve never met, never even dared to imagine, notice the “b,” lying on its side like half a pair of spectacles, clawing at the dirt, making its slow, crooked way out of the cold, damp soil. Skip right past it to the profusion of beet-colored magnolia petals carefully blinking open.

It’s not my fault Riley Kajowski doesn’t like me anymore

He did last week. We were sitting in Biology lab and he put his hand on my leg and said, Olivia, you’re da bomb. We were dissecting a sheep brain. My friend, Chloe, who’s in 11th grade, said frogs are worse because they look like what they are, only dead. Riley’s knee was touching mine under the table. Scalpel, he said when I handed it to him, his voice all serious. The sheep brain had these pouches that look like worms with bumps. It was gross but interesting if you know what I mean. Riley plays goalie on the JV soccer team. He’s got a grin that tilts and eyes the color of sea glass. There’s the pituitary gland, I said, when what I meant was you’re really cute. The brain was slimy, and we both wore gloves. It stank so bad we covered our noses with the tops of our T-shirts. I kept thinking five minutes ago that brain was in a bucket at the front of the classroom and before that it was inside a sheep and the sheep probably lived in a field somewhere with grass to munch on and clouds overhead. What a waste, Riley said, like he’d read my mind. We were supposed to find the nerves. If I knew what was going to happen later when Riley came over and sat on my bed, which Mom wouldn’t have let him but she wasn’t home because Aunt Charlotte fell and broke a bone in her foot and someone had to drive her to the hospital, if I knew then we’d do things to each other’s bodies and I’d leave mine behind, not floating above it because that sounds like heaven, more split off so there were two of me disconnected – which was weird – I wouldn’t have laughed when we stuck pins in the thalmus, when we poked and prodded like it wasn’t once part of something else. I like him so much because he’s smarter than he pretends to be and he listens when I talk and remembers stuff I’ve said. That poor sheep. You think it was a girl? Riley asked and I wondered why Mr. Benevento, our Biology teacher, didn’t tell us that, why nobody thought it mattered. We cut the brain together, his hand over mine, so the right and left hemispheres came apart. Severed, Riley said.