He said I suffered from kukolnost, or puppetness. I didn’t know what he meant by that. Most of the time I couldn’t understand his English and I spoke very little Russian. As a result, I often found myself nodding insensibly when listening to him. I called him Max as I had trouble pronouncing his Russian name—spelled something like Mactep. He once told me what it meant in Russian, but I’ve forgotten. Sometimes I feel like I don’t have a proper memory, that it’s scored with inexplicable holes or lacunae. My childhood for instance is a gray, impenetrable fog. But my memories of Max remain crystalline to this day.

We had met at the local chess club, which was really my dentist Dr. Boris Kulig’s semi-finished basement, furnished with six or or seven bridge tables, plastic chess boards, plastic Staunton chessmen, and faux-wood chess clocks. A Keurig coffeemaker kept the players refreshed and wired, and smoking was only permitted on the back porch, where more than a flew fled for relief during or after a tense battle over the board.

Max—a new patient of Dr. Kulig’s—and I played six or seven games of five-minute blitz chess. With his penetrating gaze and wild hair he bore a resemblance to Mikhail Tal, the sacrifice-happy Russian chess genius. After crushing him in our first clash, I thought the whole Russian chess mystique was propaganda. But when he soundly defeated me in each successive game, laughing loudly each time I resigned or my clock flagged, I was humbled.

“You are weak,” he told me, his laughter blunting the bite of his judgment. Despite that, we struck up a species of friendship.

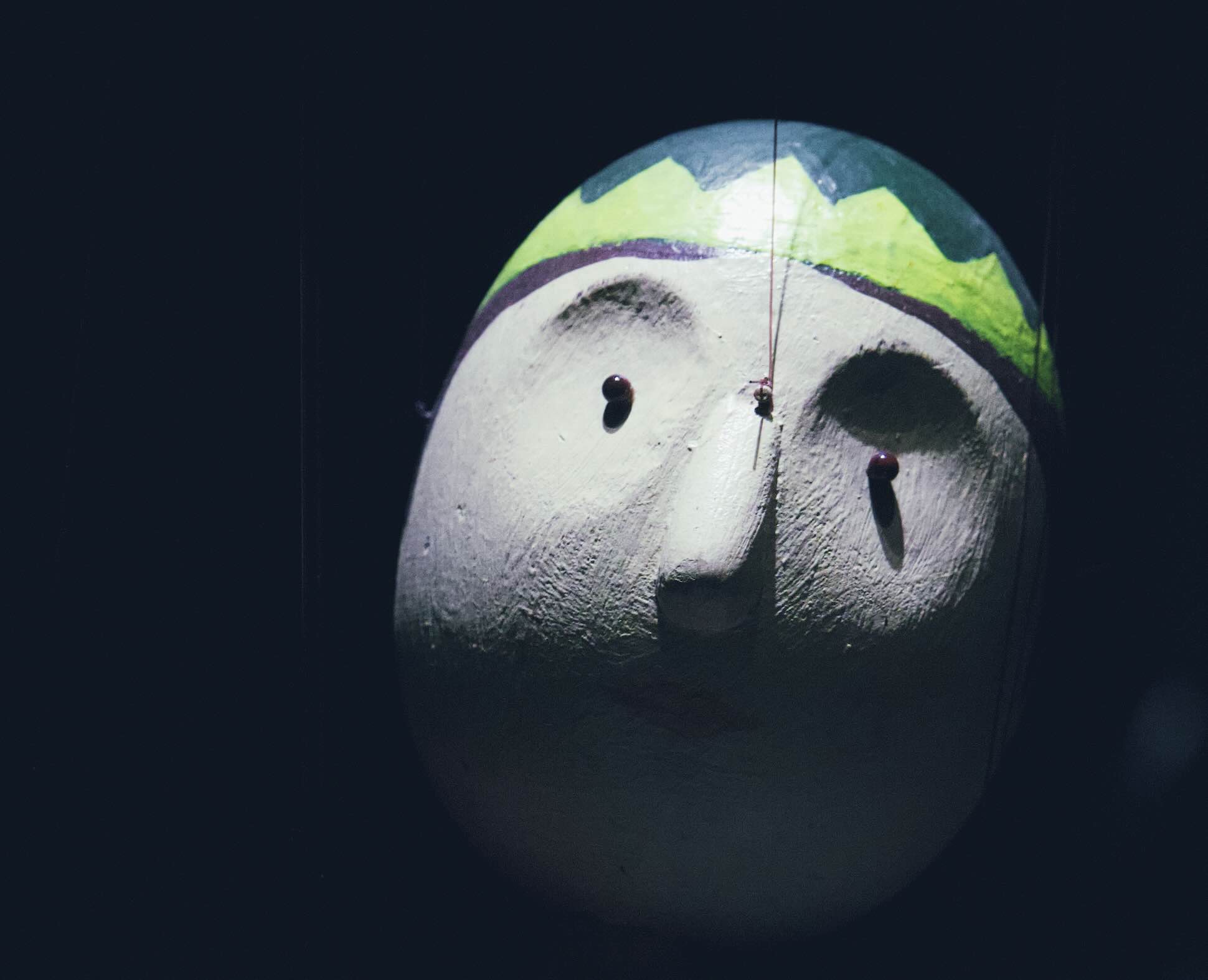

We went for long walks and spent hours chatting in cafes. Russian authors were among my favourites and we talked at length about Isaac Babel, Gogol, and of course Dostoevsky. But Max’s great passion was puppets. He’d studied at the Central Puppet Theatre in Moscow before emigrating to the West. He often went on about Russia’s deep puppetry roots, dating as far back as the sixth century under the influence of the Byzantine Empire and even the Mongols. Indeed, our conversations eventually became nothing but Max’s fervent monologues on puppetry. He never told me if he was an actual puppeteer or a puppet-maker. I assumed a few puppets languished in his closet, but never pressed him on it.

One evening, long after his shtick had grown old, he virtually forced me to go see a film with him about puppets—or acted by puppets, I no longer recall—at an animation festival.

“Remember this name,” Max enthused, “Sergey Obraztsov. The father of Soviet and therefore Russian puppetry. Strong proponent of finger puppets, and also skilled in puppeteering free hand. He is responsible for this amazing short film.”

It had the unusual title, Looking at a Polar Sunset Ray, which was probably poorly translated Russian. I’ve not been able to locate the film again despite exhaustive online and library searches. I do not recall the puppets being particularly appealing. And over the years the film itself has faded in my memory to a series of strange, static images. But there’s more.

Max enjoyed the occasional blotter of LSD. He liked how it disordered his senses and made everything look different. I’d long ago stopped indulging in dangerous psychotropics, but on this occasion he’d convinced me to be companionable and drop a hit of LSD with him. So we had gone to see this puppet film stoned on acid like two hippies from the 1960s. How astonishing! How astonishing the swift passage of time! On this occasion, though, time had slowed down. The puppet film seemed to creep along for hours. Others in the theater looked on with gaping mouths. But as the LSD worked its lunatic magic, I had the uncanny feeling that under the influence of the film or some other agency, they’d actually transmogrified into puppets, for they did not move. They blinked their eyes and clacked their teeth in a facsimile of laughter, but they did not move their heads at all and not one got up during the performance to use the washroom.

Max watched the movie with his head tilted completely back and his mouth open as though he were receiving refreshing rain or manna from heaven. Why we continued to be friendly at all defeated my understanding. He had few redeemable or charming qualities. He talked about puppets incessantly and I could barely understand anything he said. And he was an insufferable misogynist, constantly peppering females young and old with lewd asides, though they often didn’t understand him. Still, his energy repulsed them. And I was repulsed. And yet, I was unable to shake him, to separate myself from him. I offer no explanation for this. There are mysteries in life we must resign ourselves to never resolving.

I recall that as we exited the repertory theatre after sitting through the bizarre little movie, I had the sudden compulsion to sprint down the street. It had rained, puddles plashed under my shoes as I clopped along, my only impetus: to put as much distance as possible between Max and me. But try as I could, straining every fiber of my being, I did not get very far when I found myself abruptly turning around and sprinting back to the theater. I couldn’t stop myself. I even tried to hurl myself to the ground with no success. Arms and legs pumping, head flung back, mouth open wide, I returned to the repertory theater with heaving lungs and heart palpitations.

“Your puppetness has no limits,” Max cried upon my return, slapping his thighs with merriment. Hands on my knees as I caught my breath, I didn’t understand what he meant at that moment. But when he jokingly instructed me to walk out into the traffic speeding by the theater and I felt my legs start to move, I feared the worse.