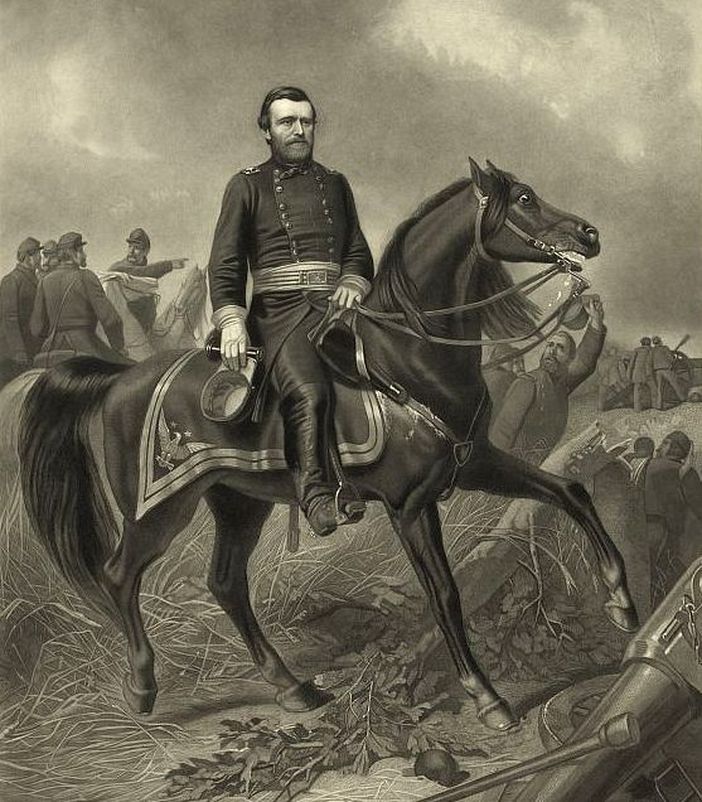

U.S. Grant slouches alone at a lowboy in the corner, neon-bearded, looking itchy beneath a halo of Pabst light, thick fingers lost in the hairy clot beneath his chin, scratching, an uncherried cigar, dourly masticated, prying open his lips–a half-cashed High Life bubbling beside him in the VFW’s finest glassware. Grant’s frockcoat sits open to his belly, its brass buttons glinting like fake coins, a poorly stitched epaulet curling at the corner, as though his rank were transitory.

Sipping coffee at the bar, I motion to Rachel for a refill and a High Life and join Ulysses in the corner, placing the beer before him.

“Much obliged,” Grants mutters, plucking tobacco from his lip, eyes fixed on the far wall.

“You can break character,” I say. “I don’t mind.”

Grant says nothing.

We sit silently awhile, Grant adjusting to having company while I drink my coffee. Other Grants–fake fakes–crowd the door, a half-dozen or more, each well-burnished and impeccably bar-lit, shining like Christmas toys, all backslaps and whiskey breath and haughty wheezing, toasting Galena’s Memorial Day Gold Star Ceremony with platitudes and here-here’s. None of them so much as side-eye Grant at the lowboy, a ghost among ghosts.

Grant slides the untouched High Life across the table to me.

“I got four years,” I say, sliding the pint back.

Grant turns and elbows the table, splattering coffee and sending beer onto his wool trousers. “Ah, Christ.” He wipes at the bloom on his pants and gives his beard a frustrated yank, his grey eyes darkening into small storms.

Grabbing napkins from the bar, I offer them to Grant. He waves me off, half-limp, and I sit back down.

“Your father a drunk?” Grant asks.

“No,” I say.

“My father either,” Grant says. “My grandfather, though, he raged. His name was Noah. He drank away a fortune and left my father with nothing.”

Upfront, one of the fake fakes gets loud, sends a glass shattering, and feigns a punch as the other fake fakes grab his lapels and shove him against the wood paneling, saying Calm down, Bill, and Get it together.

“The Biblical Noah was a drunk too,” Grant says. “After the flood, he drank himself naked and passed out in his tent. His son, Ham, found him, and instead of covering the old man, fetched his brothers to gawk.”

Calm down, Bill makes one last feeble lunge, gives up, and all the fake fakes go back to drinking as though nothing happened.

“When Noah awoke, he grew furious, cursing Ham and enslaving all of Canaan. Southern boys eventually bastardized the Word, claiming the Curse of Ham to be a justification for their ways.”

Grant drags a weathered palm across his mouth.

“All that hurt,” he says. “Passed down by a drunk.”

Neon-drenched in the half-light of the VFW, Grant looks somber and lost.

“What am I doing here?” he asks.

“Choosing a side,” I say.