UNREGULARITY

Our father told my brother, Justin, “Everyone forgets regular people.”

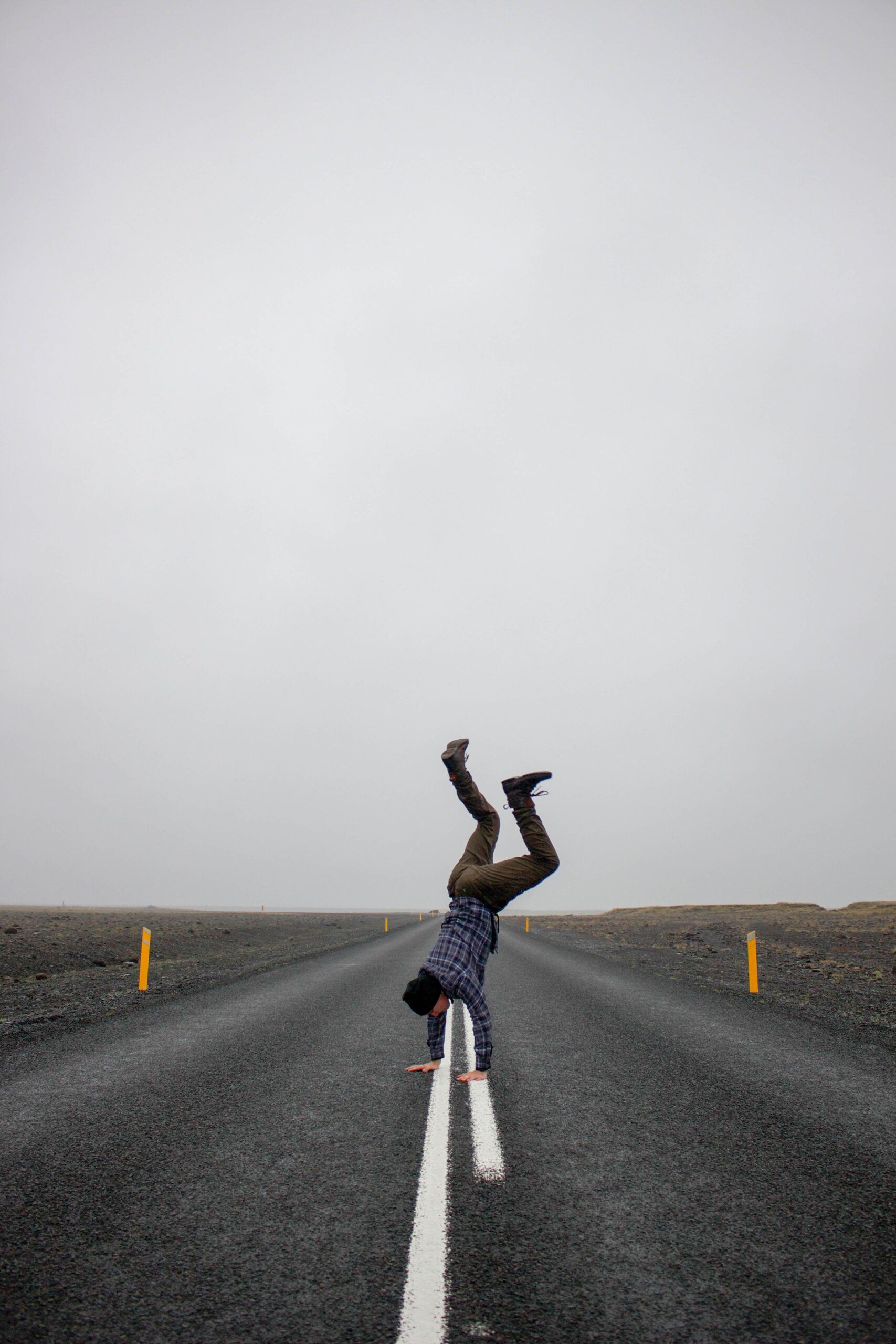

So Justin declared his birthdays to be “festivals for unregularity” and then “irregularity” after being corrected, then back to “unregularity” for the sake of being unregular. He celebrated his 8th birthday by standing on his head, only to come down when our mom scolded him for not participating in duck-duck-goose, which he diligently did but returned to eat his cake up-side-down, declaring, “We are not like birds; we can swallow in space.”

He canceled his 9th birthday, declaring it to be an unregular year, much to the annoyance of his friends. On his 10th, he invited only girls even though he thought girls were boring.

Our parents grew tired of his self-declared unregularity, and they told him, “People like normalcy.”

Justin responded, “What’s the point of being liked if you’re forgotten?”

Our mother retorted, “Well, you’re too old for birthdays, anyways.” Despite throwing me birthday parties until I was 16, which my brother noticed with regular objections.

This spread my brother’s unregularity to other parts of his life. He quoted Shakespeare despite never getting above a B+ in English. His favorite was Hamlet’s speech even though his friends never allowed him to finish. His second favorite was Portia’s description of contrition. Upon realizing he was not good enough to be a professional athlete, Justin quit sports, but our mom talked him into signing up for the soccer team anyway. He made assistant captain and the regional finals in his senior year. He tried dating another guy, but our dad said it was wrong to include this as unregular, not to mention Justin’s uncomfort with the bulge in the other guy’s pants. But Justin became a jock with gay friends. Jerry became his best friend. Other kids routinely joked about it, and he shrugged his shoulders with silent pride. He wore bell bottoms, bringing a subculture to a part of the school, and he did not drink, then did. He went to modern art exhibits featuring drip paintings, abstract hanging sculptures, and memoirs on the body. I asked him, “Do you like them?”

He responded, “I’ll learn to like them.”

He signed up for Philosophy at university and spent years studying political philosophy, from Hobbs to Rousseau. He debated whether or not ethics was defined by our intent or the consequences of our actions. He bothered me over dinner about the limits of science, which as a cellular biology student, I did not believe in. “Can we know what it is like to have the conscious states of a bat’s echoic sonar by studying neurological functioning?” he asked.

I saw his point but did not want to give in. He insisted, “Can we ever know what it is like to be a bat with objective knowledge? Think of a color-blind person studying the light spectrum and neurology but never having the visual experience of red or blue. This is so much more than that!”

“No,” I conceded.

He leaned back with the grandest smile.

He became a feminist—a radical at first, and then a moderate—and explained how the concepts of “male” and “female” are self-fulfilled by performative behavior. And he waxed poetically about what Socrates started thousands of years ago and how “The good life comes from learning how to be a good person.”

He graduated with honors, debated going into graduate studies, and then he settled on applying for jobs in Communications. He first worked at Alta Pipelines, but he quickly moved to Wolly’s Foods. His job title moved from Junior Communications Officer to Communications Officer and is currently Regional Head of Communications—where he substantially increased and highlighted their weekly donations to the food bank. One night, while eating steak and potatoes, a dish he would not eat 10 years ago, he declared, “I love making bad news bearable and good news exceptional.”

“Why so?” I asked.

“I’ve learned to find the upside in everything.”

He met Clair at the office. They dated for a year and a half, moved in, and recently got married. Jerry was his best man, and he jabbed barbs at him as “the most unregular guy I know,” causing Justin to bury his face in his hands. Jerry ran over and hugged Justin mid-speech as he laughed and blushed. Clair got Justin into recycling. They are down to two bags of garbage a month. They bought Chevy Volts, then Teslas. And they volunteer as writing tutors with at-risk youth.

Justin continued going to art exhibits no matter what the topic. I went to one: Our City in History. As we gazed at photographs of the city skyline evolving from four-story walk-ups, then ten-story buildings, to fifty-story skylines, I asked, “Do you like the other exhibits?”

“I learned to love them.”

“All of them?”

“Yup.”

“No more being unregular.”

He smiled, “You remember my birthdays.”

“I remember they were canceled.”

He chuckled, “Everyone is forgotten; what type of a person do you want to be?”

WALKING THROUGH MEMORIES

I glance over to see 3:27 glowing on the alarm clock. Collapsing into my pillow, I feel sweat beneath me. I look over at Jeffery. His arms are curled up into his chest. His side lifts ever so slightly, then falls back down. The moonlight speckles the ceiling. It globs through the leaves and branches, like water dripping through a strainer filled with seeds. My feet are tingling, and my calves are spasming. I am ready to run a marathon. My mind already is. I try focusing on nothing, then on my breath, but my legs start twitching, and I sigh. I swing my legs off the bed and rest my elbows on my thighs while bouncing my left leg on the ball of my foot. I push myself onto my feet, grab the towel from the bottom bedside drawer, and lay it on my back imprint, pressing down, careful not to wake Jeffery.

I step into the main area of our condo, slipping on a tee shirt as I go. I take a last look at Jeffery curled up beside my towel. The moonlight dances on the wall. ‘The storm didn’t come,’ I think, ‘but the wind sure did.’ I line myself up with the space between the TV stand and the coffee table. I slowly put my left foot in front of me, feeling the cool hardwood on my heel, then on the ball of my foot, as I rotate forward. “Breathe in, breathe out.” I think while I feel my ankle turn, and I take another step. ‘Breathe in, breathe out.’ I repeat as my mind calms, quickens, then calms. I think, ‘I’ll never sleep tonight—no, return to your breath.’ Sweaty footprints form behind me as I make my way across the room. I notice a picture of Jesus and a cross sitting on the buffet behind the dining table. I smile, walk over, pick them up, and place them in the buffet drawer, returning to my walking meditation.

Lining up with my furniture, I take a step. My mind wanders… I look up from the pews at a group of adults, scrunching my face while I fiddle with my tie. Two women wear bright red lipstick, black dresses that cover their arms and drape down to their lower calves, and gold studs in their ears. They listen to their husbands chatting with my childhood priest. The men laugh first. The women laugh second. One woman holds a full collection plate. She gazes at the priest as he chats with her husband. The plasticity of the woman’s eyes seems so…

‘That is a thought,’ I label it and bring my attention to my chest: lifting and pausing and falling, lifting and pausing and falling. My shirt sticks to my shoulders. I tug at it, and it feels moist as it drapes on my skin. I turn slowly and deliberately at the kitchen island. I feel the stiffness in my right ankle as I twist and take a few more conscious steps… My priest’s eyes dart about as he stands at the pulpit. They are catatonic. His arms move with emphasis. I am bewildered by how he speaks: “For it was Jesus who flipped the table of the money changers. He banished them from the temple, and he cleansed the temple of their greed.” I sneer, staring at his hands as they slice through the air, rising and thrusting on the emphases. His hands are large, and there are several rings, gleaming gold and sparkling diamonds, on his fingers. His hands reach out, molesting the minds of the congregation, and filling the nave with gobsmacked eyes…

‘Thinking,” I label this digression, and I turn my attention back to my left foot as I place the toes down first for a change. It pushes my hips forward, and my back arches as a raise my arms for balance. My toes bend, sliding slightly from being placed into a footprint of sweat. I lower the rest of my foot. My toes straighten. My right fingers brush against my boxers. I pick at the fabric between two out-stretched fingertips and focus on the feeling between them and the feeling on my outer thigh. I hold my breath and turn… those eyes, those plastic eyes. Or is it made of bronze? He hovers above the priest, looking down. His arms stretch out. His feet are crossed. I stare into those eyes. My priest has different eyes: Lively. Commanding. Condemning. I scowl at those eyes.

‘Thinking,” I note as I take another step. I remember dinner. My mom did not say anything, but she knew that I was trying—for her. She knew I was being polite. She once said, “It isn’t Jesus’s fault.”

“I don’t know.” I said, “What does he do?”