The Answer

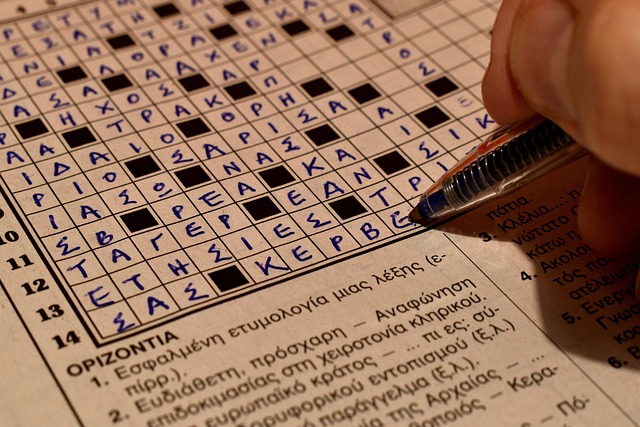

Toby and Eleanor sat at Gate B44 waiting for their flight to Cancun. Toby held coffee in a beige paper cup. Eleanor read The New York Times, pen in one hand, folded magazine section in the other.

“Guppies,” Toby said. “27 Down.”

“Thanks,” Eleanor answered. She recrossed her legs and bit the bottom of her lip. It was six-fifteen on a Sunday morning.

Toby lifted the cup’s lid and blew away the steam. “Einstein,” he said.

“What?” Eleanor studied the black and white page.

“7 Across. Einstein.”

Their flight was at seven. The terminal was empty save for one sleeping man and an old couple sharing a donut, hunched over and picking at the frosting like birds.

“Oh,” Eleanor said.

“E-I-N—”

“I know how to spell Einstein.” She brushed a strand of dark hair away from her eyes.

“You didn’t fill it in,” Toby said.

Eleanor worked her pen across the paper. The ballpoint made small holes.

Toby sniffled. “Do you have a kleenex?”

“What?” Eleanor could see pale blue—her faded jeans—on the other side of the pinpricks.

“My nose is running.”

“Look in my purse.”

Toby plucked the purse from behind her sneakered feet. Her black bag in his lap, he peered over her shoulder.

“Canada,” he said.

“Stop,” Eleanor said, chin tucked, the end of the pen between her teeth.

“8 Across,” he said. He watched two planes: one taxied to the gate, one rolled to a runway. The sky was gray.

“Stop,” she repeated.

“I’m just trying to help.” Toby rummaged. Her keys jingled.

“I don’t need your help.”

“Fine.” He took out a mint. He wiped dust off the clear wrapper. “You don’t have any kleenex. But I’m stealing this.”

“Fine.”

“Good,” he said. He dropped the wrapper back in her purse. He sucked the candy. He put her purse on the empty seat beside him and picked up his coffee. He blew over the rim. He cleared his throat.

“Crepes,” he said.

She turned to him. “One more word and you’re flying alone.”

“I’m hungry,” he said.

“That’s not an answer?”

“No, it’s not an answer. It’s a suggestion.”

“Then good.”

She looked back at the page. Toby sipped his coffee.

She poked her pen through the paper and jabbed her thigh. “Ouch,” she said. Then: “Fuck.” She rubbed her leg. “Screw you.”

“What?”

“21 down. Crepes.”

“Oh? Really?”

Eleanor stood and dropped the magazine in Toby’s lap.

“No,” she said.

“What?” He held his arms open.

“No. I can’t.” She shook her head. “I mean, I won’t.”

Steam rose from the open cup. “What?”

“That’s my answer,” she said. “I’m sorry.”

Eleanor crossed to his other side, hoisted her heavy purse.

There was nothing to slide off her finger. No reason to reach out to Toby’s empty hand, turn it up, and set something in the middle of his warm palm. Nothing gleamed in the dim winter light. The ring was on a baggage cart, on the tarmac beyond the window, packed in Toby’s suitcase. But she knew it was coming, knew from the moment he’d told her he’d booked the flight, the hotel, the restaurant on the beach for tomorrow night, knew the minute he told her he’d arranged everything and all she had to do was go along. She had waffled at first: sun sounded fun, an escape. But now she knew the correct response.

“No,” Eleanor said again.

She walked the carpeted corridor. She passed an attendant heading Toby’s way. She paused, spoke to the uniformed woman, and kept going. Maybe Toby tried to guess what she’d said: Excuse me or Watch out for him or Seems I won’t be flying after all or, again, to everyone this time, I’m sorry. Or none of those at all. Maybe he finally came up blank and he couldn’t imagine what she had to say to some stranger, maybe he couldn’t explain the situation or offer an answer, his take. Maybe he was, finally, silent.

Eleanor sensed but didn’t need to turn around to know: he was still sitting, staring at the puzzle in his lap, a man accustomed to supplying all the answers, but now with half the boxes empty, half of them complete.

One Hour Drug Tests While U Wait

And there the man sits in the Chevy’s driver’s seat reading a month’s old Rolling Stone and scowling at the four-starred review of Nicki Minaj or an auto-tuned teen-age blonde he’s never heard of but wouldn’t mind screwing if she just promised not to sing or dance or say his name, not once, not aloud. But this is unlikely.

Maybe he scowls over his application to the chicken “processing plant”—oh, hell, call it what it is—a slaughterhouse, please, for chrissakes—a place for killing—and it disgusts him, and yet, and yet he needs the work, the dollar more than minimum wage hardly a wage at all, his last gig three states west of Nacogdoches, this college town which once seemed a logical place to crash, so many guys he knew here in school, but suddenly, they’re all gone.

They’re gone, graduated, married, maybe they’re in other cars, not like his, better, mini-vans and SUVs, plush seats higher off the ground, and they are waiting for little boys in baseball and littler girls at ballet, not reading about pop bilge and wondering about THC levels, the unwise burning of that joint two nights ago, even then fully aware of this requirement, this urine hurdle he ignored, or pretended wasn’t there.

Now, his window down, its scratched glass possibly stuck for good under the lip of rubber like an eyelid on the sill, he missed the days of cranks. Uh-oh, they broke but it didn’t cost three hundred dollars to fix a freaking door motor dedicated to doing one stupid thing which it then failed to do it.

He missed cranks. He missed his buddies, he missed Bud, and he missed bud in brownies and he missed the warm cup of piss he rested on the magic window ledge of the little bathroom in that clinic right there, the clinic across this short parking lot, that window with the lazy susan for the nurse to spin and take that cup of him and test it. Of course, he didn’t want to work drunk or stoned, though killing that much for eight hours a day has got to be easier done high, easier than sober, it’s gotta be, but he knows there might be sharp blades involved, or maybe he’ll just work the hose, washing out the stuff nobody wants, a steady shower over all those pale corpses, and he wants a shower, yes, a shower. The car stinks with heavy Texas heat and car exhaust and his poor attitude, that’s what everyone who was anyone in his life has called it, has always called it, poor attitude, and this music sucks, and radio everywhere sucks, and this magazine sucks.

He pulls on his cigarette and, oh, that’s good, so good and thank God or Whatever’s there, there’s still one thing in his world that isn’t messed up.