One afternoon, the summer before I started junior high, I left my younger brother to die frozen and alone in the English countryside. I’m speaking metaphorically, of course. The nature of this metaphor will become clear to you very soon.

Not metaphorically, my younger brother and I rode our bikes to the local Aldi grocery store. I say our bikes, but they were really just a couple beat-ups my dad had bought cheap at a police auction. The ride to Aldi, not a trip we took frequently, was about an hour long ride up and down shady hills and cracked sidewalks right alongside the Ohio River.

The town we grew up in was humid and mundane. It started as a pioneer frontier riverboat town, and had become now a generic Anywhere, USA with a Walmart and McDonald’s and a rampant meth problem. We had to get either creative or stupid to entertain ourselves. On this day, we decided to be stupid, and the setting for that stupidity would be the Aldi grocery store. While we rode, I followed my younger brother, Isaac, and tried to hit his back tire with my front tire so that his bike would become unbalanced and he would fall down.

He asked me to stop, and I didn’t stop.

The wide Ohio River ran slow and brown and ugly beside us.

Isaac, one year my junior, shouted to me something about an airsoft gun he wanted buy, and I said something like “That’s cool” or “Whatever.”

Isaac’s hair was jet black. Not naturally. He dyed it. It was all black except for a little strip in the front that he had dyed red, but which had turned pink after a single wash. Me and the rest of my siblings had laughed about it both behind his back and in front of his face.

But then one time after we laughed at him, he cried and locked himself in his room and taped a note to his door listing the few people in the world who were allowed inside. None of us made the list.

After that, we only laughed about it behind his back.

It was hot and humid and sticky out, as most summer days in a town by a river are. By the time we reached the grocery store a smear of muggy sweat had accumulated between my butt cheeks, leaving a long, dark streak on the back of my pants as I got off the bicycle. We always referred to this condition as ‘Swamp Butt.’ A difficult medical condition at any time, but especially irritating while committing misdemeanors.

My brother and I had a plan for our trip to Aldie, as far as twelve and eleven year old boys are capable of planning anything.

The Swamp Butt hadn’t been part of the plan.

But as according to our plan, my brother went in first.

I waited a while before going in after him, so staff wouldn’t know we were together. Two separate sweaty boys are less suspicious than two sweaty boys together.

As I stepped inside, blissfully cool conditioned air swept over my dripping forehead.

Isaac always tried very hard to put me down. He’d dig at weird little faults and embarrassments, usually things I’d never before considered the need to be insecure over. But like all things in his life, he could never focus his attention on one insecurity for very long. He constantly bounced between different wannabe-insecurities.

Once, it was handwriting. Isaac had better handwriting than I did, and he never missed an opportunity to flaunt the disparity. Unfortunately for him, not many opportunities to flaunt your handwriting really occur in the day-to-day of things. So he made his opportunities, usually by asking me to write something for him, and then laughing about how my V’s and the R’s looked the same.

One day, while we rode in the backseat as my dad drove us to the grocery store, Isaac harped on his handwriting spiel. He asked, “Brett, who in the world has worse handwriting than you?”

I shrugged and said, “A blind person?”

To which he cried, at the end of his wits, livid, “You are blind!”

He was a weird kid.

Another time, it was about penis size. Isaac claimed to have a bigger penis than me. I claimed not to care.

His argument was that he had once snuck up on me while I was in my room (an incredible claim, as Isaac still stomps so loud everywhere he goes it sounds like he’s wearing twenty-pound iron galoshes at all times), found me inexplicably butt naked standing in the middle of my room, boyhood proudly on display. I stayed gloriously erect and fantastically oblivious long enough for him to secretly complete all the proper measurements. He came to a swift, damning conclusion—his was bigger.

He made sure to tell this story to everyone he knew, both friends and family.

Again, he was a weird kid.

Nowadays, I suspect these attempted-pissing contests must have been the product of a cripplingly low self-esteem. He needed to put others down so he could better handle his feelings of inferiority. But at the time, they were bewildering and irritating.

To his credit, though, my Vs and Rs don’t look the same anymore. Through conscious effort, my handwriting has improved by leaps and bounds since that day in the car.

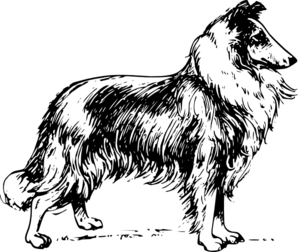

Now let me tell you something about Lassie. You know, the dog. Because Lassie is everything I’m not.

The beloved mascot of ideal canine-human romance known as Lassie first appeared in a short story titled “Lassie Come Home” written by Eric Knight and published on December 17, 1938. In 1940, Knight published a novel of the same name, and in 1943, MGM adapted the novel into a feature film. The novel and film attained enormous financial success, while Eric Knight is credited for creating a permanent icon of American culture.

Lassie was also a plagiarized lie.

In Lassie Come Home, the movie, set during the Great Depression, a down-on-his-luck father is forced to sell his son’s collie, Lassie, to a rich duke.

The boy is heartbroken.

Lassie later escapes from the duke and returns to the son.

Neither Lassie nor the money paid for her are ever returned to the duke, a passive and socially acceptable form of theft.

But it’s a story about loyalty, not morality.

What most people don’t know is that the character of Lassie already existed before Eric Knight’s story. English author Elizabeth Gaskell published a short story in 1859 titled “The Half-brother” featuring a collie named Lassie who behaves identically to Eric Knight’s Lassie.

Gaskell was long dead and forgotten by the time of Eric Knight’s success, and of course he never credited her. Why would he?

In one of the grocery store aisles, I made sure no one was watching and then picked a couple packs of gummy candies off the shelf and shoved them down into my wet underpants.

In my pockets, they would have produced a noticeable bulge, but the groin is the part of the body where a young man desires to possess a bit of bulge.

Across the way, I flashed Isaac a thumbs up. He had been acting as lookout for me, looking out for me.

He nodded and the ridiculous pink stripe of his hair fell into his eyes. He swept it away, his hand shaky. He turned and moved into the next aisle over, and I went to aisle entrance to act as lookout for him, to look out for him.

“The Half-brothers” by Elizabeth Gaskell is a story about two brothers who journey far from their home one winter night on a vague errand from their father. On the return journey, they get lost in the snow.

When it becomes obvious that the situation is hopeless and they will not reach home before freezing to death, they send their collie, Lassie, ahead to fetch a rescue party.

Then they lie down and wait in the dark and the snow and the ice.

I became bored waiting for Isaac and went back to the other aisle to see if I could fit an extra box of moon pies in my underpants.

“You!” I heard a loud masculine voice shout on the other side of the aisle.

The voice wasn’t directed towards me.

I went around the aisle and saw my younger brother, his shoulder in the firm grip of a tall angry store manager.

My brother looked at me and I looked at him.

His eyes were scared and desperate.

None of Isaac’s putdowns ever bothered me much, except for one. It was the only one he ever stuck with for any sustained amount of time.

As we entered middle school, we both hit puberty, and our hormones informed us both of how vitally important it was to be accepted by our peers, to bend to social norms, and to have friends.

And there Isaac found his greatest weapon.

His latest and greatest put down became the belittling and heartbreaking declaration that he had many more friends than me, was more popular than me, and was better with girls than me.

All of these things were true, and we both knew it. It hurt when he pointed it out, and we both knew it.

One night, after another bout of sibling bickering, Isaac said, “If it bothers you so much that you don’t have any friends, why don’t you just make some friends?”

In the grocery store aisle, Isaac looked at me, and I looked at him.

The store manager dragged him towards the store’s office, and Isaac still looked at me. The manager said, “You’re in big trouble. You’re going to wait right here until the police come.”

I walked out of the grocery store. With the distraction, I got out without any trouble.

I left him behind.

But what could I have done for him in that moment? Why should I feel guilty?

In “The Half-brothers,” by the time Lassie returns, the brothers have both collapsed and been buried halfway in the snow.

The younger brother passes out. The older brother remains awake.

Lassie can rescue one of the brothers by digging him out and dragging him towards the coming rescue party, but only one. The brother who gets left behind will be condemned to hypothermia and death.

Back outside the grocery store, I picked up my bike and rode down the street a block. I waited and watched the store entrance. I still sweated, now around a groin full of crinkly gummy candy wrappers and a blocky box of moon pies.

Eventually, a police car pulled into the parking lot.

The officer went into the store.

He came out a while later with Isaac. Isaac wasn’t handcuffed, but walking alongside the officer.

The officer directed Isaac into the back seat of the cruiser. I was too far away to see his face.

The officer went back into his car and drove away.

I didn’t know then what the consequences for Isaac would be. I didn’t know if he would be arrested, if charges would be filed, what the punishments could be. I imagined the worst.

In “The Half-brothers,” the older brother commands Lassie to rescue his unconscious and dying younger brother.

He sacrifices himself for his brother, and then dies.

It is a beautifully optimistic story.

They were looking out for each other.

I have five brothers and sisters, but it was only with Isaac who I spent hours and hours building ship-shod towns and convoluted stories out of lego blocks.

It was only with Isaac that I spent a month playing a game of the Sims in which we roleplayed as a married couple recently-moved to a new town.

It was only with Isaac that I snuck out of youth service on Sundays to go play in the creek behind the church.

It was only with Isaac that I spent winter evenings lighting plastic army soldiers on fire in the backyard.

It was only with Isaac that I once broke into a Myrtle Beach pier after midnight to steal beer and ice cream.

It was only Isaac that I held as he cried after getting jumped by a group of pot dealers and promised to never tell our parents.

And it was only Isaac that I let be arrested as I watched, as I didn’t join him, as I didn’t do anything to comfort him, not even a mouthed, ‘It’ll be okay.’

Only Isaac that I let freeze to death in the snowy English countryside, while I roasted sweets by the fire.

But Lassie is a lie, and I don’t have to feel guilty for this.