The pit bull gives birth to seven but two come weak, some ill luck that marked them inside their mother. They are too feeble to latch, and even if they could, the warm bodies of their brothers and sisters would refuse them. The bitch does nothing but lie on her side and leave her milk exposed. Her eyes stay open as her pups suckle, what ones that can. Those open eyes hardly blink. It seems strange to the woman, she who found the pit bull a dirty creature coming on feral in a ditch outside Mill Road, who gave the dog some semblance of ownership against the outrage of her husband, him who watches from the long distance of the open door, a cold wind trickling in around him. The bitch gave birth in the tool shed, on the bare dirt between a tarped lawn mower and a white bin of rakes, shovels and hoes. The woman knows why her husband stands with the door open, all of winter behind him. He does it to remind her to stand herself, to stretch her legs and walk with him back to the house. She ignores him and stays kneeling before the pups.

There is electricity in the shed. A light bulb gives yellow light from the rafters and a small space heater blows hot air. With the natural barrier of a closed door and four walls, it keeps warm enough for the pit bull and her pups, and so there is no need to worry and every need to stand and walk out so her husband may shut the door behind them. Yet she strokes the heads of the runts a moment longer. She has tried every trick she remembers or suspects, but nothing can coax them into strength or their mother into compassion.

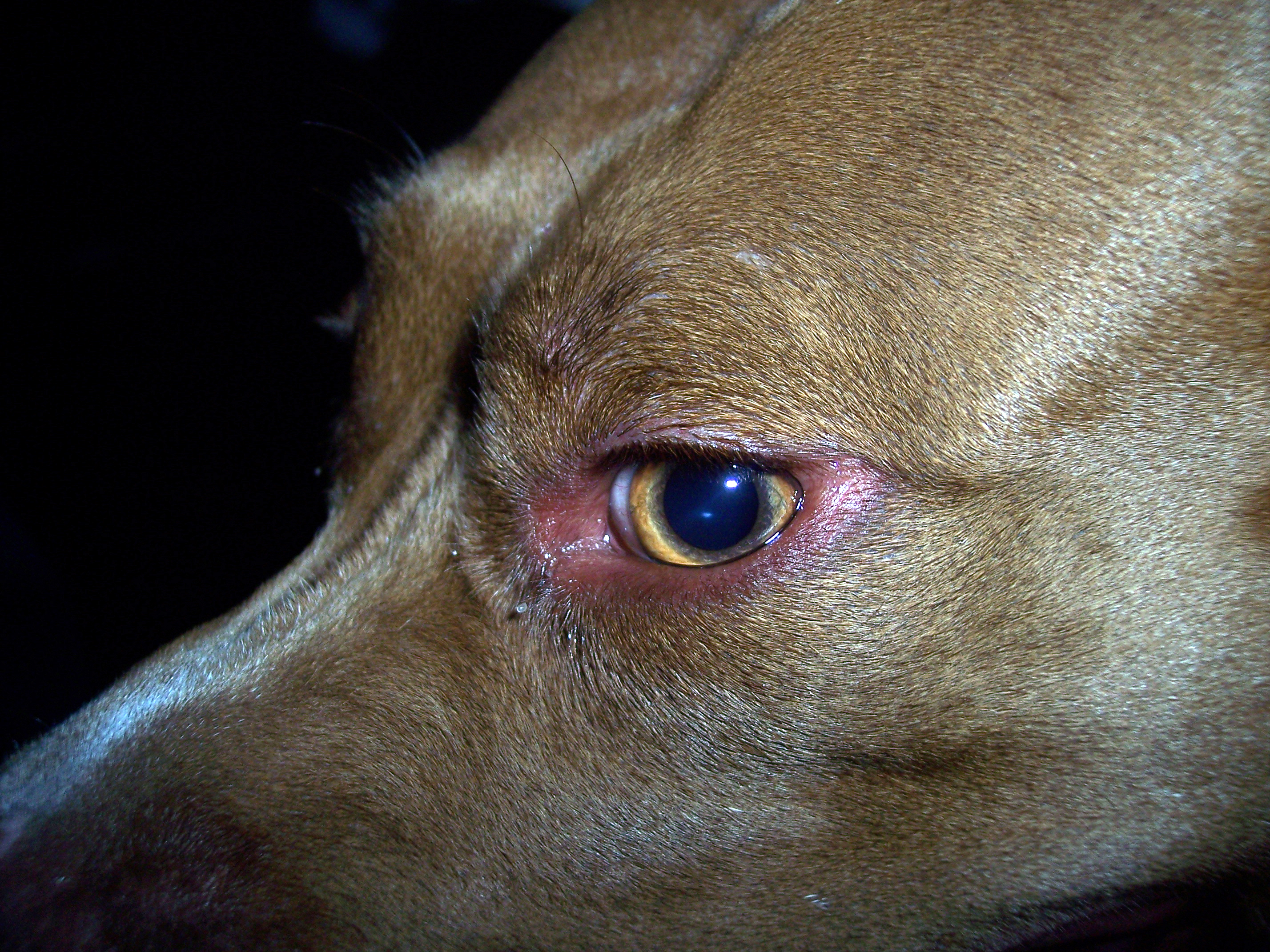

Her husband is waiting for her to give up and she knows why. They have too little money to spare to call any sort of animal doctor, especially for something as hopeless as this. Very soon these runts will die. They will die hungry and pathetic, suckling the dirt. She will find them with their mouths open, the stillness of their bodies of no concern to the other pups or the bitch mother with her horrible open and unblinking eyes. The woman has never known a beast could be so vacant. So emptied. She thought this expression belonged to people alone. It shakes her faith. Her husband, she knows, senses this and wishes to spare her of it, this knowledge and that ultimate sight. Her husband and his large hands, holding the runts, cradling them into his palms, each into the soft vise of his touch, until their breath is undone. And then he will bury them or else throw them in the ravine a half a mile down the road. She will not acknowledge this. Maybe, when she was younger, when life was open before her, she might have had the strength to forget these ill-fated creatures. But now, her own body hollowed by years and surgery, the runts have become too precious to leave. So she ignores her husband and his voice and the winter air and stays in the dirt, placating this new mother to spare the pups her husband’s gentle hands. But those open eyes don’t see, and the earth has gone cold beneath her.