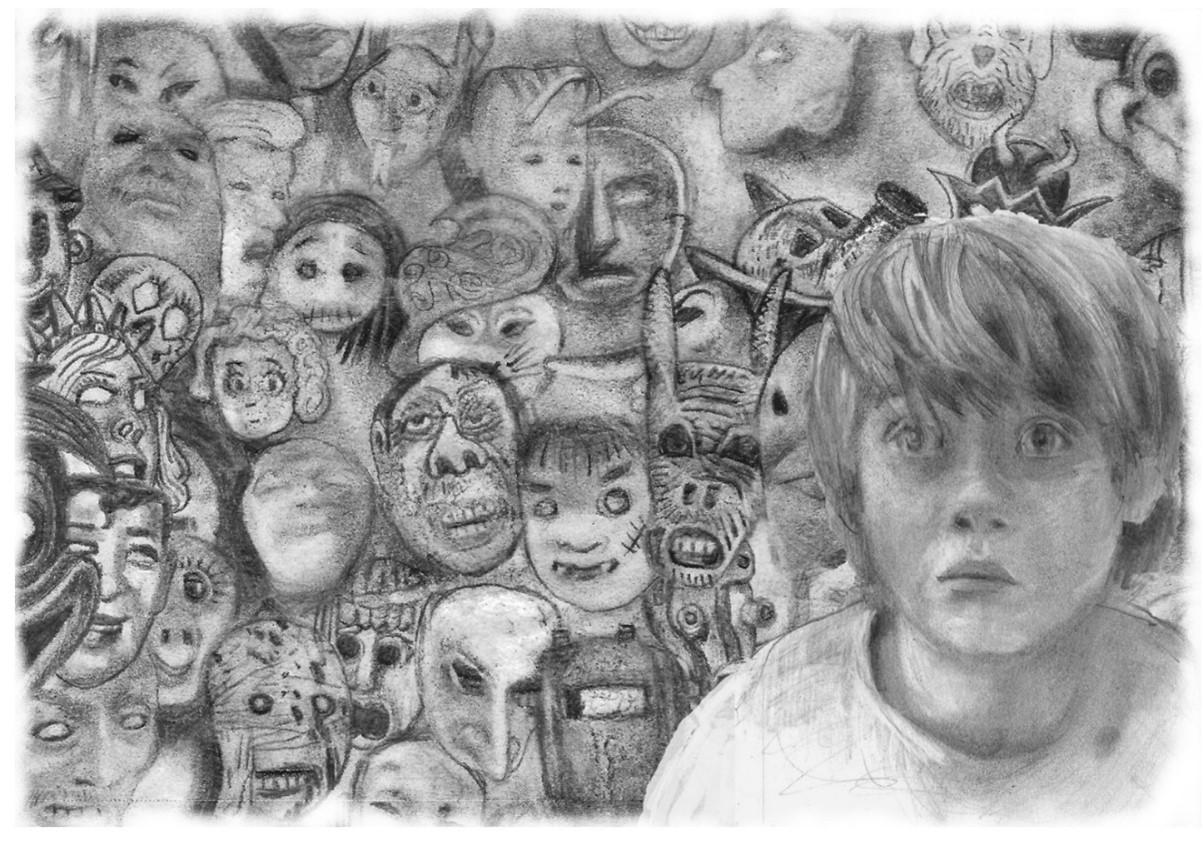

Carlton Biff could see through my masks. His eyes were almost yellow, set in a feral, near-albino face aflame with acne. We goan fuck you up boy he hissed. I had hundreds of masks in my collection, but Biff saw through all of them and hated what was underneath. It seemed to me that there was an imprint of a lost me on the inside of a certain, special mask. A me that wasn’t lost and afraid. Could I find the right mask? Maybe it didn’t exist, and maybe there was no me to find at all.

There were many places to search out masks: toy stores, variety stores, party supply stores, gift shops, candy stores and stationery stores. But the most important source was McCarthy’s Drug Store. To find the masks you passed racks of comics and shelves of hair dye and laxatives to the back, where the window to the prescriptions department was cut into the wall. The red mortar and pestle symbol promised some old magic within– alchemy, elixirs and potions to cure all evils, or summon them. A sharp turn to the left led to the soda fountain and four booths lit by a large picture window facing the sidewalk, where men and women in hats sent loping shadows across the floor. Easy to miss in the turn was a small, dark area just before the soda fountain. Here was the mask area, with all variety of gods and monsters, heroes and villains, the new in the ancient, the ancient in the new waiting for the next wearer to claim a new (or maybe original) face for the bright world.

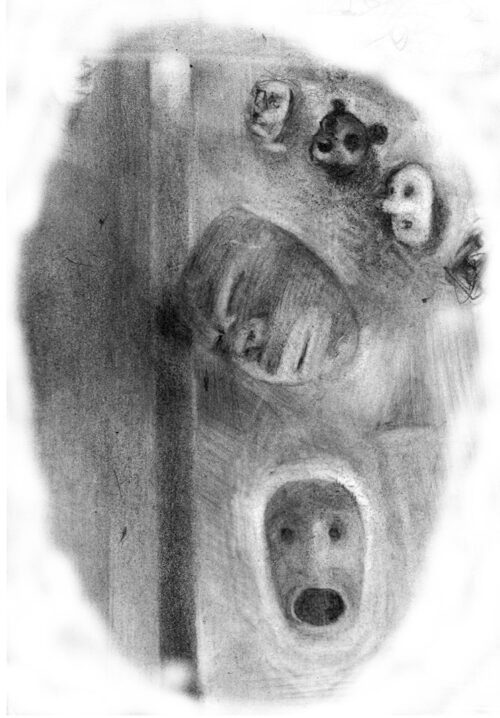

One day while I was on my knees looking at a mummy mask in the toy nook Carlton Biff grabbed me from behind and pushed my face into the mask. The mummy face had a strip of bandage unraveling like a dangling tongue. The eye holes weren’t slit, but poked. The dark inside beckoned. The touch of Carlton Biff began as a shoulder pat, almost friendly. I didn’t bristle, and it was easy to be pushed to the floor crumpling the mummy mask with my face, like bowing down to something greater than any pharaoh or fane.

The moment was like a kiln, firing the experience into a hardened vessel of ceramic RIGHT NOW, maybe a mask to hang on the wall of masks I had in our basement recreation room. In that moment Carlton Biff pushed my face harder into the mummy mask, so hard I couldn’t breathe or move. I heard the mask crumple and crinkle, and I was more afraid for it than my own face.

When he let go and left I was relieved to find the mask, with some manipulation, pop back into shape, and I was able to put it on to cover the blood and bruising I felt on my face, and to buy the mask from Mr. McCarthy while wearing it to cover my wounds. I looked through the eyeholes of the mummy mask down at my empty hands. My eyeballs flicked the sharp edge of the eyeholes. The mummy mask was an old-style vacuum mold, thin and rigid as an insect carapace. I teared up a little in the eyes and would have taken the mask off if it were not for the bruise and blood on my face, which was so sore and numb that speaking much to Mr. McCarthy was difficult. I tried to leave. Mr. McCarthy instructed his assistant to take over the cash register and took me aside. He tipped my head back with a thick finger under my chin and lifted the mask. We went to the back door into the pharmacy section. There were many bottles on shelves and smells from the bottles. I told him I had fallen. He murmured, “re—al—ly?”

He dabbed gauze on the bruise and on the cut. Gauze came away red. He applied hydrogen peroxide and I felt fizz. He told me it would be ok and asked me again what had happened. I told him I believed I had tripped. His face darkened.

I think Mr. McCarthy could smell a little bit of the smoke and burned skin. He applied very cold water to the burns, and then petroleum jelly, little squares of gauze, and soft bandages. thought of the mummy mask.

“What happened here? It looks like cigarette burns.” I told him that was not possible. That I must have fallen outside, fallen on something. Something that was ground into me. Burning things. Perhaps still lit candles on a birthday cake that fell out of the hands of a birthday child. Or the still burning twigs of a boy scout who had just been practicing the Indian technique of rubbing two sticks together to start a campfire and given up just as the wood sparked alive. Or perhaps three upright live electrical wires that had fallen from a downed powerline. Or perhaps the sting of three fire ants, angered that I had stumbled upon their hill of a colony.

But I should back up and tell about what happened a few days before coming home from school. Somehow, I ended up in a garage tied to the chair and was burned by Carlton Biff and some others I couldn’t see. I was able to persuade Mr. McCarthy that the three burn spots on my chest had been made by one of the things I told him had happened: that I had fallen on a birthday cake with three lit candles; or that I had fallen on a burning stick that had broken into three pieces with three flames; or that I had fallen on a downed power line with three frayed wires spurting electricity; or that I had fallen on an ant hill colony of three large fire ants. Falling on something was the key. Mr. McCarthy seemed satisfied by the idea of falling on something as the explanation.

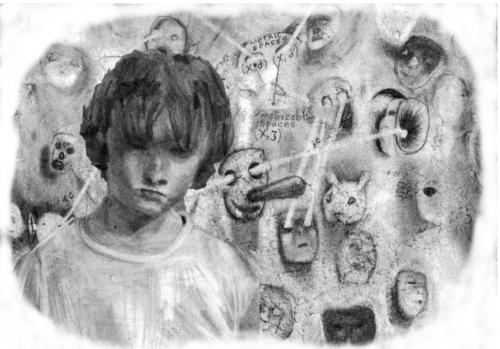

Later in the mask room I hung the bloody mummy mask in area that included a brown, fur covered rubber Wookie mask, a silver and red, globular-eyed Ultraman mask, a beak-nosed, Commedia dell’arte Scaramouche mask, a plastic, black and green vintage Creature from the Black Lagoon mask, a plastic Mickey Mouse Mask mask, a white, red-lipped Noh Theater mask, a Greek Theater Comedy mask, a plastic black-haired witch/hag mask, a Guy Fawkes mask, an orange and purple Dios de los Muertos mask, a leather and cloth plague mask, a Congolese Kuba leather and wood ritual mask, and a gold plastic Ironman mask. My eyes kept going back to the Greek Tragedy mask. This one was had the bloody eyes of Oedipus Rex. I was sure I was hearing something coming out of the mouth, a hollow moan. It was no message that could be written down or understood to be made part of the system or help build all the systems into the system even though the Greeks had the essential frame for anything. It was not something from my mother’s cassette tapes of The Wide World of Knowledge or the radio university on the air, but something that not only rearranged or remade or reoriented the system or systems of sets in my head, but opened up an emptying, a whistling blank in the center.

For a time I was too scared to go out, but finally I returned to McCarthy’s drug store and looked at the comics and masks. Mr. McCarthy was in the cramped pharmacy window between the big red RX and the mortar and pestle sign. He was wearing that old-fashioned white jacket with buttons across his shoulder, like an old movie mad scientist, Lionel Atwill or Boris Karloff or Albert Decker or J. Carroll Nash. Mr. McCarthy asked me if I’d like to help him with “some liquids.” The back room was lined by buckets and glass jars. They were filled with milky white stuff and individually lit in pale red, orange, purple, green and blue. Were there shapes inside, slowly sinking and rising again? I helped pour liquids as Mr. McCarthy instructed but got scared again and said I had to go home. When I returned the next day I stayed hidden behind the mask racks and watched Mr. McCarthy. He was talking to customers from the prescription window. I stood and he waved me over and said he could explain about the liquids. He walked me out the front door and pointed at the window display. Under the white lettering of PRESCRIPTIONS was the row of big glass jugs holding colored liquids. As I’d seen in the back of the pharmacy, small colored lights hidden at the bottom made the color glow. At the end was a cone-shaped beaker, hanging from a curling black metal stand. This beaker’s liquid was colorless. We came back inside and he said the liquid was not medicine, but colors closely associated with potions, elixirs, alchemy.

“You can help me change out the liquids every week,” he explained, “so no cloudy residue compromises their power. These tonalities play on vibratory planes. I light them from below with imperceptible colored Christmas lights. They produce a radiance that builds confidence in my product.” Later I saw new colors in the window display, odd combinations of off-whites like freezer-burned skin. The largest jar was lit with the same acid yellow I’d seen in Biff’s eyes. It wasn’t long before he was prowling through McCarthy’s. I cowered in the mask and toy nook, waiting for his approach. Biff stopped by the display rack of masks and turned it slow, gazing down at me as the faces wobbled by. Behind him Mr. McCarthy in the narrow pharmacy window called over to Biff and invited him to enter the pharmacy door. The door closed and the light in the pharmacy window dimmed. The inexplicable betrayal overwhelmed me with nausea, vertigo and terror. Exhaustion and despair pushed me into something like sleep. When I woke it was dusk. I crawled out of the cubby and ran into Mr. McCarthy. “You’re still here? You should be home. Your mother will be worried.”

I stared past him at the mortar and pestle symbol, and the RX. The wall between them that had been the prescription window was blank. I asked him what happened, but he didn’t answer. “What about Biff?” He looked at me blankly.

I said, “The boy.”

“We won’t be seeing him again.” I couldn’t move. Then when I did, it was to throw my arms around Mr. McCarthy. I pulled away without a word and fled. As I ran down my street I tried to forget the last thing I had seen in the mask rack: a new mask, the color of acne on albino, with cigarette butts ground into both yellow eyes.