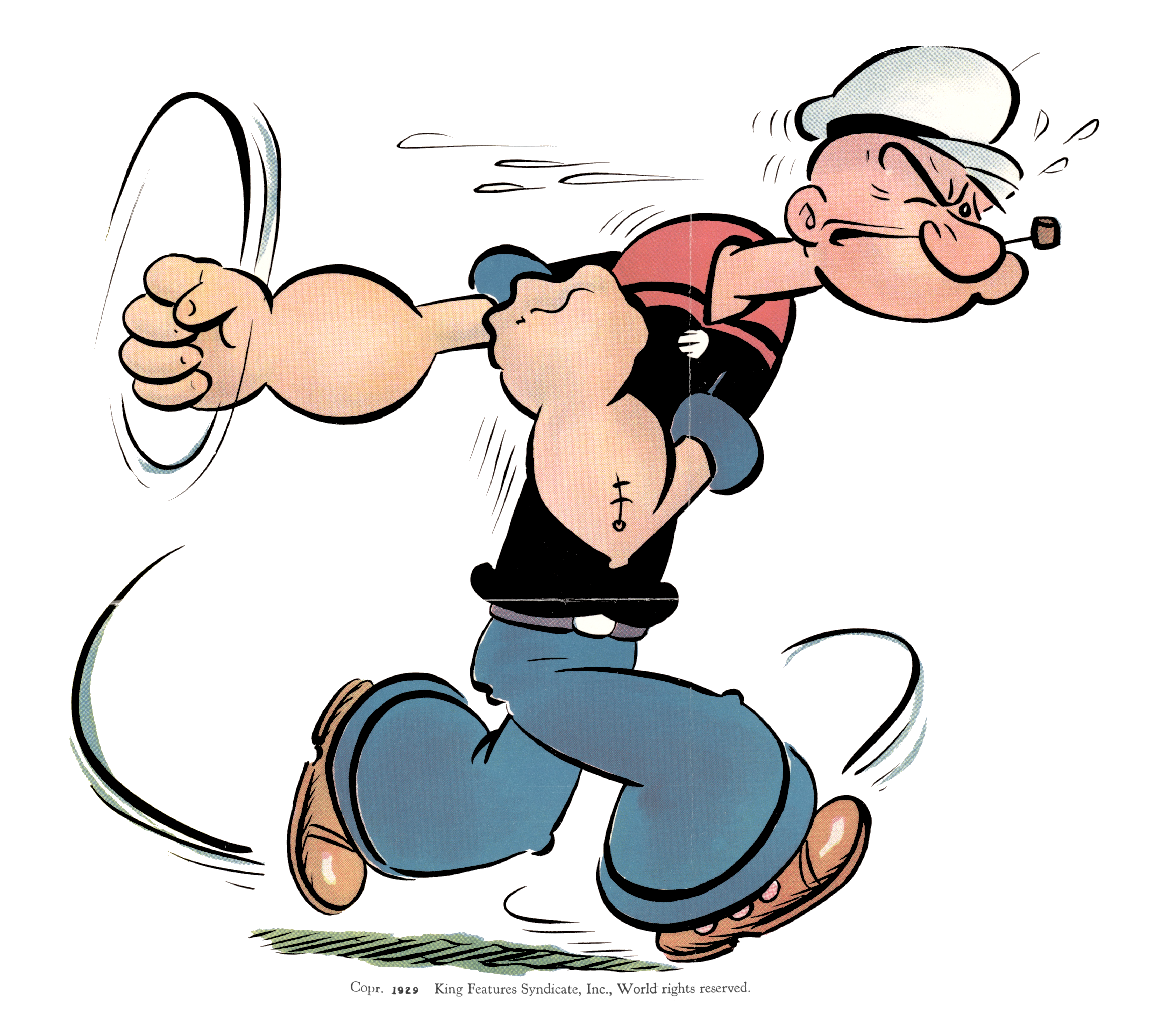

Another bomb threat at Christa McAuliffe Memorial High got the Ross children home from school way early. Just before noon, bright October, the four walked into the narrow kitchen and stopped short to see Mom in bathrobe, hair messed, butt against stove, fridge open, its light on her face. Entirely wrapped in the super muscular arms of a man. Not their father. Shirt off, belt undone, the orange mustachioed guy’s Popeye tattoo expanded across his chest with each deep breath.

Mom and man unclenched, overhead fluorescent coloring them both a little blue. His mouth opened, but wordless, the gap filled by Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here up way loud, same as Leila, eldest, seventeen, liked to play their Dad’s—the real Dad—scratchy old vinyl.

“Popeye likes Pink Floyd?” Leila muttered to Patrick, two years younger. “Ugh. I can’t wait to go to Stanford.”

Patrick heard nothing, only thinking, “Maybe now’s a good time to use the knife,” and eyed the longest of the super sharp set the kids were prohibited from using/touching. He could easily plunge the terrifically dangerous blade right into the Popeye tattoo’s eye, jack it out and then, for good measure, back into the orange-haired man’s actual eye. Yes, he could.

Young Max, who wasn’t sure they wanted to be a boy any longer and had taken to wearing rouge since the start of the school year, pushed a drooping hairlock off their forehead and wondered if the gun their father supposedly had somewhere in the house really existed and if they, Max, could find it fast enough and have the balls, or whatever, to shoot Popeye. They didn’t move.

“Two point three months more and I’m gone.” Leila sighed, early admission to Stanford approved, though a just-delivered letter from that very university sat on the dusty La-Z-Boy in the sun porch, a letter that might not be good news.

Rosa, Max’s twin, smacked her lips and tried a smile. “Good for Mom,” Rosa thought. ‘Stupid Dad’s always away with the FBI or whatever his bogus job is. Away for weeks. And when he’s home he’s got like a literal ton of paperwork. Forever busy up in the crummy attic.’ She thought about Dad playing his records up there, too. Really ancient albums, like Led Zeppelin or The Who, but mostly prehistoric 45s, one song per side on his cranky record player, changing them every three minutes because the dumb thing won’t play a stack automatically anymore, not since Mom kicked it. Rosa also thought Mom was actually right to kick it, when Dad had told them this summer he’d miss their vacation ‘cause he had to go out of town again. But, Rosa wrote her diary, I don’t believe one bit Dad’s at freaking government meetings all the time!! I just know he has a whole second family, (truth!!) with other kids, too, living on the other side of the river, in New York eff-ing City, where he goes like every Saturday, alone, even though we all—except smartass Leila, of course!—have literally begged him for years to let us come.

“I’ll take you next time,” Dad usually said. But next time still hadn’t arrived.

That, dear diary, Rosa wrote, is proof of family numero dos, who get to live in the hugest lux-o apartment where they probably can literally see our crap house from their penthouse window, and where the doorman calls taxis for them when they’re on their way to some fancy-ass restaurant and a play! “No wonder Mom’s in the arms of Popeye,” Rosa thought. “Good for Mom… Empowerment! But this guy? Popeye?”

Mom closed the fridge door, rattling the catsup bottle while Max wondered if they took the plunge and became a girl and grew into a woman, would they want a lot of lovers calling, a lot of men, say, and if so, would there ever be any man with a Popeye tattoo across his chest, or any tattoos at all, or a mustache – an orange one, at that. They looked the man over with care, noting he was way younger than Dad, probably twenty years, for all Max could tell, the guy’s curly orange hair so opposite Dad’s slicked back gray, tinged with some leftover black, receding farther from his forehead each time he looked. Popeye worked out, for sure, barely any chest hair, too, though his arm hair was way thick, and that led Max to think the man shaved his chest for effect. Max supposed they’d have to shave a lot to keep hair off, if/when the transition happened, though probably hormone shots took care of that and they’d have no worries about shaving. Who wanted to shave? All those nicks Dad came out of the bathroom with, little pieces of toilet paper and a dot of blood keeping the torn paper bits stuck on his neck. Patrick had been shaving two years already and could have a full beard in a week if he let it go, which he didn’t, except that one time when he got busted.

Mom cinched her bathrobe top with her hand. She had her damn diamond ring on, Patrick saw. He rubbed his palm across his stubbly cheek. He’d only done a quickie shave that morning, cream left over on his earlobe, before he grabbed two slices of toast, held in a paper towel, margarine smearing his finger, a small container of OJ from the three dozen Mom bought each week, running after Leila, Rosa, and Max, none of them ever rushing like him. Then Patrick focused right back on the knife, thinking, ‘what if I took it and killed or seriously hurt Popeye? Could I get the sibs to say I’d done it in self-defense? Would Mom contradict them, betray me, too? Look at her, purple bathrobe all frayed at the bottom.’ Patrick never knew how anyone would treat him, never truly felt part of the Ross family like the others. He was pissed, too, that he needed the shave because if he did grab the knife and jam it into tattoo Popeye’s eye and Orange Hair’s eye and the cops came, arrested him, then by the time they booked and photographed him he’d definitely look like the derelict Dad kept telling him he was, and no judge would ever buy his story, no matter how good he made it, or if the fam – like they might ever – concurred. Same as with the bust, when he barely hit possession limit. Three joints. Or was it four? No matter. What was wrong with smoking weed and an occasional snort of smack? Weed’s already legal in like twenty states, for crying out loud. Patrick could only name five, though. He passed his palm over the other cheek. Rough, too.

“Listen, kids,” Mom said, hand grasping bathrobe, other hand pushing the fridge door when it started to buzz, loud. Rosa watched the second hand of the kitchen clock’s smooth sweep, saw it pass over some very calm stream in woods, where not a sound was heard from the clear, gold water, thousands of squishy minnows, tiny fish mouths open, closed, open, water flowing, flowing, as the clock’s hand slid, like literally, away.

“Kids,” Mom started again, scrunching her fingers into the scratched kitchen table while Leila also checked the clock, feeling every damn elongated second, each one getting her closer to leaving, closer to flying out of JFK—definitely JFK, not slummy Newark – to the West Coast, to magic Stanford. Maybe she’d never come back, not even for holidays. Why should she? To hope she’d see Dad who’d not be home? Or find Popeye had moved in, Patrick strung out, Max growing breasts, and Rosa, who knew, maybe knocked up, just like that? No. Forget it. She’d join the Marines or move to Mexico or marry someone—though not at all like Dad or Popeye. “I’ll never come back,” Leila mumbled, deciding right then enough was enough, she absolutely wouldn’t return unless one of them died and then she’d just come for the day, a quick first class ticket in, show up at the cemetery, leave before the person – the body – got buried, and out. Definitely.

Mom cleared her throat, like they weren’t all paying absolute attention. “Kids. This is ______,” Mom said a name, but as if a spell had been cast or a cosmic interruption occurred—well, not as if, because some weird, meta interruption had occurred, and not Leila or Patrick, not Max or Rose heard the same name for the guy. A different one registered with each kid, none right, none memorable, and none replacing what they later all agreed was and must always be Popeye.

“Why would a guy named Rod have a Popeye tattoo on his chest,” Rosa wondered. “Connection, please?” she wondered equally, as had twin Max, if she’d ever have a boyfriend with such a weird tattoo, but more so, in fact, wondered about the question that she tried to deny, the one too scary to voice but which shook her insides, made her squirm, squeezed her heart, stomach, and soul: “Would she ever have any boyfriend at all?” As much as she tried to squelch it, that was the question attached as a clause to too many thoughts bubbling up in her always-bubbling consciousness.

“This will be good,” Max thought, waiting for the guy’s name to be something cool, but hearing a blah Sam, a totally non-revealing name, though kind of like Max, one that goes either way, gender-wise. Cool? No. Not really. Un-cool, in fact. Max thought: at least I won’t have to change my name. “No nickname, either, just Max,” and decided they’d never take a lover with a nickname. That would be a credo and a qualifying test. The more they thought about it, the more they felt maybe no lover at all. But wait. F that. They wanted a lover. Lovers! Scores of them. Maybe lovers who didn’t declare gender, like they soon might. Maybe! There’d be so many permutations and possibilities. How many? Max never did well at computation. They’d ask math wiz-o Leila, after this stupid stuff with Mom and Sam—or whoever—finished.

Leila figured the age differential between this Tim guy and her. “Eight and a quarter years, exactly,” she said to no one, a numerical assumption, for one of the few times in her brilliant life.

After the fridge settled, no bottles rattling, Mom said, “Kids. Listen,” and despite their disdain and sarcasm, Leila, Patrick, Rosa and Max sucked in their collective breaths, a simultaneous inhalation held, waiting for what was too clearly a prelude to the announcement of the end of the Ross family. “We want to tell you…”

The sun porch door’s creak open stopped Mom. It slammed closed, and a shout broke through the still pulsing Pink Floyd.

“Hel-lo. Anyone home?” Dad, newspaper under his arm, pushed his head in the kitchen, wheelie luggage rolling over the dining room rug’s frayed end, luggage handle tight in his hand, thick stack of folders spilling from his leather shoulder bag. “I got an early flight home. Thought I’d surprise you all and…”

In that frozen moment Mr. Ross saw his own duplicity doubled back at him. He read the entire bleak scenario in an instant, no need to get the facts, government training kicking in on cue. He blinked once, twice, muttered, “holy hell,” and by Dad’s third blink Patrick leapt, grabbed the off-limits knife, yelled, “No fucking our mother, Dave,” and thrust at Popeye’s chest. The man shifted his huge orange-haired forearm an inch, two, deflected the blade. A pencil-point line opened on his thick arm. Blood appeared. Four drops hit the white, crumb-covered vinyl tile. Mom screamed, the knife dropped, and the man they all would forever call Popeye planted his heavy booted foot on it.

Utter stillness followed. The quiet sat on top of the Ross family, plus Popeye. No one breathed. Their hearts didn’t beat, no blood pulsed. Yet each of their plans, their dreams of future and not-yet-but soon-to-be murky past, their hopes and fantasies unreeled, with hundreds more scenarios added, possibilities filled to bursting with absolute terror, others with ecstatic release, revealing the truth of not only their own life, but of each person who shared the small, still, kitchen that October day.

The clock struck twelve noon, precisely. Dad turned, and walked backwards, out the door.