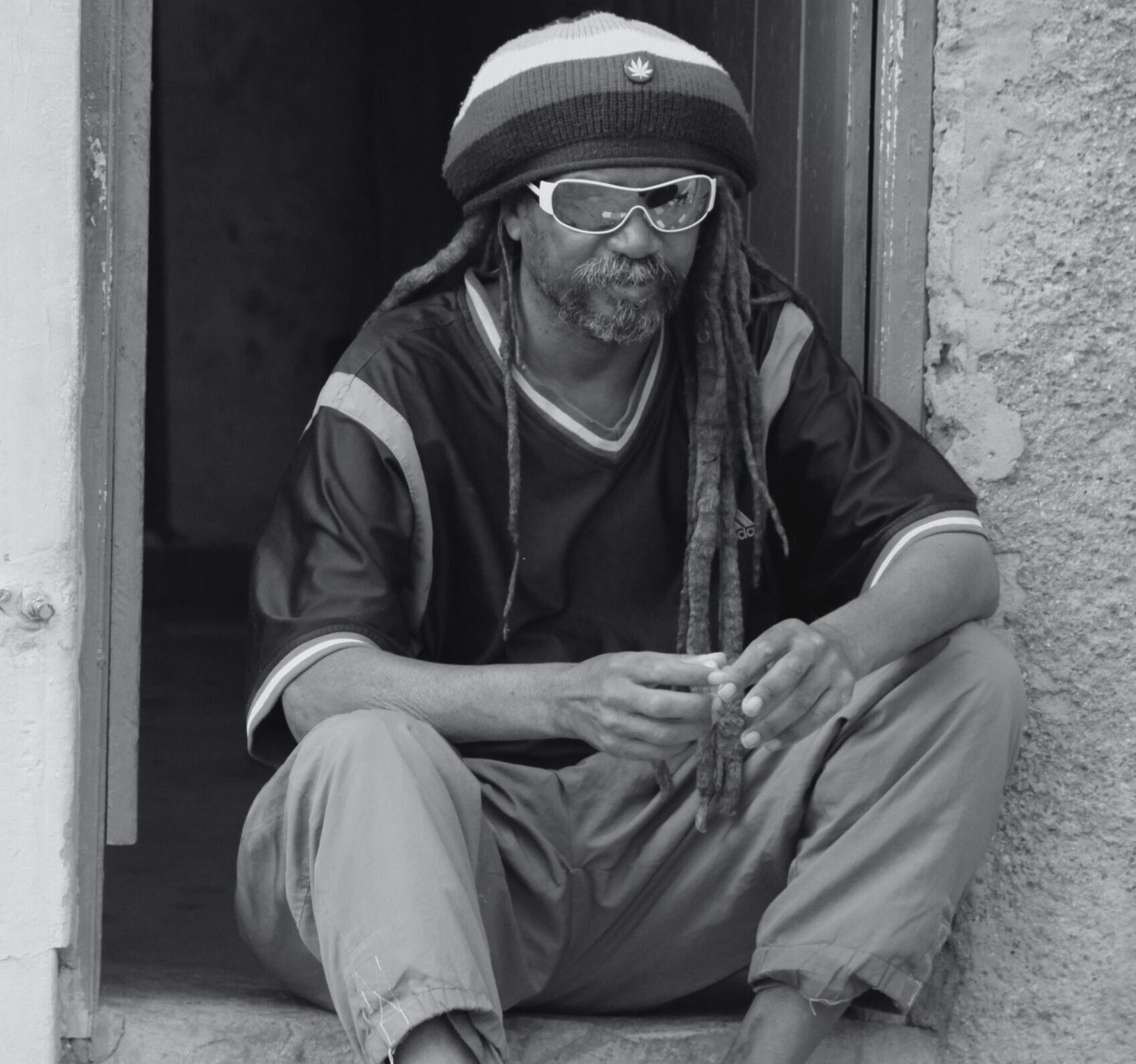

Pierre Freeman was an artist, raconteur and dancer, destitute and a drunk. He tatted his hair to thick dreadlocks that flattened into the shape of oak leaves. He smoked weed, but never paid for it. He spoke with a Jamaican accent even though he had never been out of Minnesota. In Pierre’s opinion it was better to be broke because then he didn’t spend money on drink. Skin as dark as black coffee, muscled as a field hand, Pierre at onetime danced Modern African Ballet with the Minnesota Dance Company. The art director fired Pierre when he showed up for a performance at the Walker Art Museum stage too drunk to do anything but pee on himself as he lay on the stage, his well-muscled ass in the air.

He hung out in the Bohemian Flats Neighborhood in Minneapolis, the punk-beatnik mecca on the west side of the Mississippi River. The University of Minnesota studio arts building stood a few blocks away. Pierre modeled for the life drawing class where he met Ester, a progressive Jewish girl, and took her drinking at the River Rat tavern. She carried a 35-millimeter camera, took black and white photos, sometimes had a show, and printed art postcards of her work. Ester always shelled out for the drinks. Even drunk, Pierre sustained his Jamaican accent.

One evening in October when the wind skipped brown, red, and yellow maple leaves up the sidewalks, he arrived inebriated to the studio arts building. Pierre managed to disrobe and then piss and projectile vomit on the nice students and their sketchpads. He then fell asleep on the small stage, his well-muscled ass in the air. The art professor fired him.

Pierre’s best friend was Arty O’Brien. A white dude of Irish ancestry, Arty had known Pierre from before the Jamaican accent. Arty lived in a storefront studio next to the Veterans of Foreign Wars bingo hall by the Bandbox greasy spoon off Chicago Avenue.

One morning just past midnight, Ester drove Pierre to Arty’s storefront, dumped him on the sidewalk, pounded on the door and left Pierre forever. Arty, hoping to run into Ester, came out barefooted and bare-chested but wearing tight jeans. He kicked through the autumn leaves, and helped Pierre inside to sleep it off on the couch. Within the next two days, Pierre found new employment at Cash Paid Daily labor pool a few blocks away. He kept his accent.

Pierre never rented an apartment. When he crashed at Arty’s storefront studio, pallet wood burning in the woodstove with a wire mesh fence around it, he spoke plain Midwestern English with a Swedish accent and not a trace of southern Ebonics. Arty O’Brien, born and raised on Stoney Island in Chicago, talked blacker than Pierre did.

“I have my story down,” said Pierre. “There’s a village in Jamaica on the northeast coast called Orange Bay. That’s where Cairo’s family keeps a farm. It has a view of the Caribbean from the foothills of the Blue Mountains, and Swift River flows from those mountains. Caiman alligators inhabit the lower waters to the sea. I haven’t been there yet but know from Cairo’s stories every path, every river, and every stone and conch shell along the beach.”

Cairo was a real Jamaican whose skin matched the color of unsweetened chocolate. Cairo dealt weed and drove tractor-trailer over the road. He was a natural aristocrat. Pierre would be if he quit drinking.

Pierre rolled a cigarette from a package of Bugler and lit it on the stove. “I grew up in the jungle, lived on breadfruit and mangoes and fish. My gran’fatah escaped slavery and went to the mountains to join the rebellion. When I tell that story I always get pussy.”

Arty knew the last woman to sleep with Pierre was Ester. Arty loved her even though he never slept with her. He’d visit her tiny Bohemian Flats apartment and sip hot tea that smelled of

orange peel. Three masonite panels stood floor to ceiling to cordon off an area for a dark room. Her living space walls displayed a series of framed black and white photographs of Pierre in various ballet and African dance poses, stark naked, muscled striations gleaming.

Sometimes, Ariel from the room down the hall would visit. She looked Arty over, her eyes dilating like she had smoked Datura, and licked the blue line edging dark red lips like a ripened plum. Arty knew better than to get with Ariel. She seemed ageless. A Rip Van Winkle story circulated in the taverns and coffeehouses that when men emerge from Ariel’s apartment, decades have passed.

“Don’t you think,” said Arty to Pierre, “you aren’t being for real with this Jamaican accent?”

“I enjoy acting,” said Pierre. “It’s part of storytelling in the tradition of the African trickster.”

“What if I started speaking in Irish brogue?”

“I’d respect you,” said Pierre. “You’d be honoring your heritage. You should go to Ireland and live among your people for a while.”

“And I suppose you should go to Jamaica?”

Pierre folded his arms across his chest and leaned back. “Why not? I’m going even if I gotta swim through alligators and sharks.”

“You know there were more Irish penal slaves transported to the Caribbean and the colonies than Africans? Thus the Gaelic accent of Jamaican patois.”

Pierre nodded in agreement. “Exactly, perfessor. Living with you, I become Black Irish, like a real Jamaican.”

Cash Paid Daily moved Pierre from restaurant to restaurant. He washed dishes or cleaned ovens or mopped up after closing. Pierre never knew which restaurant he would work at, except it would be on University Avenue.

Winter in Minneapolis began on Halloween with a blizzard resulting in three feet of snow. By Thanksgiving, the temperature dropped to zero degrees Fahrenheit. The Mississippi River froze solid. Two weeks before Christmas, the temperature dropped to twenty below zero. Pierre could risk a shortcut to his labor pool job by trotting across the Mississippi.

Arty O’Brien let Pierre move in since he was working, could split the rent and help scrounge pallets to cut into firewood. Arty was an addict too, but went to meetings. His worst addiction was taking care of drunks because his dad had been a drunk and he had taken care of his dad.

Pierre often showed up hammered, reciting to Arty from the street, “You are the best-goddamned Irishman who ever lived, and I love you more than any brother.”

Arty would get him inside and to bed.

The real Jamaican, Cairo, would sometimes park his pickup in front of the storefront and come in for a cup of black coffee. He looked around at the books, piles of lumber and parts of musical instruments. Too cold for cockroaches. At least the dishes were done. Not a woman’s crib.

“Bunk you guys in tat same bed?” he asked.

Pierre and Arty threw their shoulders back and looked at Cairo like he was crazy.

Cairo shook his head. “You misunderstand. Slept I and my brother in te same bed.”

“There are two lofts here,” said Pierre, indicating the salvage scrap 2 by 4 and Plywood structures along the walls.

“You got te Yellow Pages?” said Cairo. “Need I to look up a heater fan for my pickup.”

Arty returned from the bathroom with the phonebook.

Cairo opened to the section and found the pages gone. Torn edges remained at the glued binding.

Arty gave a sheepish shrug. “Ran out of toilet paper.”

“Mon, never buy toilet paypah. Steal I tem yella napkins from Subway.” He handed the phone book back, and Arty returned it to the bathroom.

“Anuttah ting about Orange Bay, Jamaica,” said Cairo. “When my gran’fatah murtaht his wife and ran to te Blue Mountains, police tracked him wit’ bloodhoun’s. He hole up far a long time. Escaped he te hounds by wai’ting in Priestman River. Hole up he in te caves of John Crow Mountain, runs nawt-ease to sout-west on te ease-side o’ te mountain. Te police shot him, but not befah gran’fatah killed two o’ tem. Admire I, my gran’fatah.”

They stood around the woodstove and drank coffee. Arty lifted the lid off the stove and stacked a bundle of pallet wood on the coals. The storefront smelled of wood smoke. The stovepipe entered the chimney where a gas heater used to vent.

After Cairo left, Pierre practiced the accent. “A NUTah TING te CAVES of JOHN Crow MOUNTtain nawt EASE to SOUT wes on te EASE side O’ te MOUNTain, follow UP PRIESTman RIVah, AHTy o’BRIen.”

Before Christmas, Cash Paid Daily sent Pierre and several Mexicans to a different dishwashing job. Arty, running out of firewood, needed Pierre to help scrounge pallets, But Pierre didn’t make it home that week. By New Year some folks at River Rat tavern speculated he had walked drunk across the Mississippi and fell through the ice. The old weed dealer claimed he saw Pierre staggering up the street on Ariel’s arm, and may have disappeared within her one-room at the Bohemian Flats Apartments.

Arty stood by the woodstove, drank coffee and contemplated the fractals of frost layering storefront windows. He had checked in with Ester regarding Ariel. Ester said Pierre wasn’t there.

When the phone rang, he picked it up. A woman’s voice yelled over the phone. It was Pierre’s mother. She was a Minneapolis public schoolteacher, so mean that Arty pitied the children she taught.

“He didn’t show up for Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year,” she said. “He’s not at the morgue and not in jail. He hasn’t stayed in touch since we quit speaking until he quits drinking.”

“Did you call Cash Paid Daily labor pool?”

“They claim Pierre was deported. Why would they do that? He was born when I shit him out at the County Hospital.”

Arty held the phone away from his ear. “He’s been talking about going to Jamaica for a

long time. He sounds like a real Jamaican.”

“My son always lied. Did he pack anything?”

“Just the clothes on his back.”

“Pierre likely called Immigration and Customs and reported himself. He’ll get drunk and the Jamaican police will see through his phony-assed baloney and deport him right back.”

“Winter in Minnesota will be over by then.”

“You’d think he’d send a postcard. He didn’t even send a Christmas card.”

“Goodbye Mrs. Freeman.”

Arty hung up and poured another mug of coffee from the pot on the woodstove. The mail slot clacked, and a single postcard fell among the junk mail in the wastebasket screwed to the inside of the door.

He retrieved the postcard. Blue and yellow painted skiffs pulled up on a white sand beach. On the back a stamp with a portrait of Bob Marley smoking a spliff, postmarked Orange

Bay.

Dear Arty,

U.S. Immigration and Customs raided the Mandarin Wok where I was busting suds with no identity card. They arrested and deported me to Kingston. I’m living on the beach, smoking ganja and worshipping Ras Teferi. Go to Ireland! Your friend, Pierre Africa.”

Within a week, Arty O’Brien practiced an Irish brogue and made love with Ester. From her mattress he reviewed the new line of postcards tacked to the sheetrock, including a black and white photo of Pierre’s glistening and muscular buttocks suspended against the sky full of stars.

He rolled out of bed, pulled on his jeans, tucked in his shirt, buckled his belt, put on socks and boots. “Mind me identity card, Ester. I’m heading out to Cash Paid Daily FAR a dishwashin’ job.”

She rolled onto her side, one arm bent to hold her head up. “Don’t roll your R’s too much honey. You sound Scots. Send for me when you get to Dublin?”

“Aye,” said Arty.