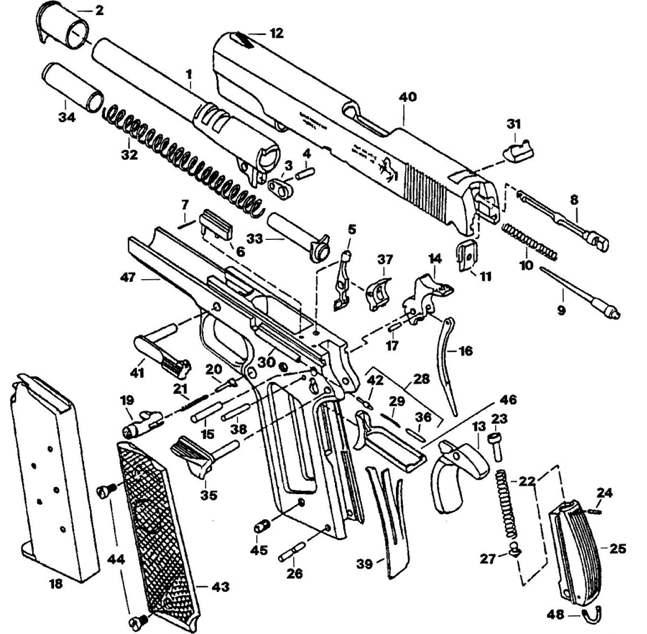

My father always had me clean and fieldstrip his combat .45 whenever he came back from the firing range. He’d hold his diver’s watch with the Navy crest to my ear and spit out orders behind me. I would clean the .45, working the pieces from a small tin of gun oil. My hands slick with oil, working old flannel patches through cleaning rods, I would clean it, I would work that .45 into life. His watch would tick tick tick as I worked cylinder to steel, worked the chamber, heard it click, my small hands fumbling to make it whole. My eyes watered. When I scratched my head he’d smack my hands hard, so I wouldn’t rob any seconds from the steel. I’d push the recoil spring into the slide chamber, forge the marriage between the barrel bore, chamber and action. Faster, he would say, when I ran the slide. I smacked the magazine, pulled the slide back, squeezed the trigger and heard the hammer click forward. The sound would take my breath. The only sound left was that tick, tick, tick. When I was done I could see him, Marlboro in one hand, his watch in the other, his eyes red, he’d tell me this was more important than school—his combat .45.

Because of him, my hands are fine instruments.

My own boy visited me here once and brought a game where you stack little blocks of wood to build a tower. You add to the top by taking from the bottom; it’ll fall if you take the wrong piece. I told him it’s like building the present from the past. He left me the game, and on good mornings I can take almost any piece and somehow make it work.

Last year, the doctor prescribed me to forget the past by keeping the present close. I started by throwing things out. Christmas ornaments, LPs, my father’s uniform all went first. Then there was the furniture. Books and clothes, the sweaters especially. When they began to wear, when I noticed on them those small pills of wool—they marked their age, marked my own age. These were the days and weeks before I fell apart.

At night, I can still hear his voice barking out the time. My hands move over the white sheet, working those pieces. I still smell the dirty oil and my father’s .45—larger than me, still incomplete in front of me. My hands bigger than my whole body keep working, but they can’t fit the pieces and I hear the watch inside my ear. Faster, he says, until I wake to the sound of that POP! and the room smells like gunpowder. My eyes red and sore. I hear that tick, tick, tick, and I know that he’s behind me and he always will be.