Something about the redneck pecking order turns the hallways of Rupshire High into a fist fest each spring. It begins as the school busses arrive. Redwings clomp across the blacktop, squishing chewed Copenhagen, cans of which ring back pockets. Left arms chokehold girlfriends’ necks and noses nuzzle into hairspray-hardened bangs. They push. They shove. They sit backwards on benches in the cafeteria, joking about the skateboard fags, band fags, and all the other acid-washed homosexuals who dare walk past before the homeroom bell rings. They pick one from the crowd, decide—“That fucker’s gonna pay for hitting on my cousin on Saturday night.” Word spreads like jock itch and by lunchtime rock hard fists hit faces with the dull thud of potatoes pounding sacks of flour. A squadron of coaches—Phys. Ed. and history teachers—mask their obvious joy at breaking up a fight. Today was no different, only the target was me, Nelson Hayes, friendless weakling.

I wasn’t even aware of the threat. I was so used to trudging through the hallways, hands thrust deep into my pockets, eyes glued to the floor keeping a running tab on the tiles beneath my feet. My problems began when I pushed up to the Coke machine and made accidental eye contact with Stacey Sedgewicke. She wore stonewashed jeans that hugged curves so tight I had to tap the brakes.

“Excuse me,” I said, looking down at her Reeboks.

She glanced at me, exhaled a loud sigh—the sort of sigh I’m used to hearing from real girls at school, not the sigh I imagine they would make as they tremble under my touch in the back of the Cavalier, the sigh that would follow the first time we make love and she tells me she’s sorry she never got to know me. No, it was that usual weary sigh, and after waiting another moment Stacey simply stepped from the machine and giggled away with her friends.

I thought nothing of this exchange until third period when Candy Williams advised me to evacuate via the fire escape since Randy Boyles, tight end for the Rupshire Crusaders and Stacey’s current boyfriend, planned to annihilate me. I wish I’d heeded her advice instead of shrugging it off, as I wrote we’re just…a Minor Threat along the white rubber toecaps of my Chuck Taylors.

No more than a minute after the bell rang did I feel the straps on my backpack pull tight as Randy yanked me into his fist. I was lying in a heap against the lockers, with a trickle of blood dribbling from my nose.

“New school rule,” Randy said. “No faggot nerds can walk around without an escort.” He squeezed his rough fingers around my collar and lifted me to my feet. A crowd had formed around us. “Another rule. No hitting on another man’s girl.”

“I didn’t hit on Stacey.”

“You don’t even get to say her name.” He held me close to his mouth. Each word stunk like wet tobacco. “Are you gonna apologize?”

“I’m sorry.”

“I thought you didn’t hit on Stacey.”

“I didn’t.”

“Then why’d you apologize, you chickenshit liar?”

Randy cocked his fist behind his right ear. I squeezed my eyes tight.

“Boyles.” Finally, the voice of authority.

Randy released me into the lockers and I wiped the blood from my nose. Coach Bryant appeared behind Randy. His hulking shoulders held the rest of his overstuffed body to its tense, athletic form. As always, he was sweating. Salty droplets dripped from his mustache like rain from a busted gutter.

“What’s going on here, Boyles?” Coach asked.

“Nothing, sir.”

“Why was Hayes lying on the ground there?”

“He didn’t get enough sleep last night, sir.”

“Cut the crap,” Coach said. “Hayes, you okay?”

“Yeah.” I hoped nobody could see the tears (of anger, I swear) that welled up in my eyes.

“Was Boyles bothering you?”

“No.”

Coach turned to Randy. “Mess up like this during the season and you’ll be running double time. Got me?”

“Yes, sir,” Randy said.

“Boyles,” Coach Bryant said, “if brains were dynamite, you wouldn’t have enough to blow your nose.”

I hadn’t seen Jonas since Christmas break, and when he sauntered into Hardee’s the next day dressed in khakis and a ripped Misfits t-shirt, I knew it was not out of some newfound fashion failure but just another example of his unnerving ability to cross-pollinate styles, never falling into a clique, always staying camouflaged. To the preppies, he was a rebellious loner. To the stoners he was a wannabe whose uncanny capacity to find primo weed made up for his trendiness. To me he was just a friend, my best and only friend unless you counted the freaks who worked with me at Hardee’s, which I did not. I didn’t care how Jonas dressed. I looked forward to hanging out with him whenever he came back from prep school.

“Take a break,” he said.

I yelled to my manager on the back line. “Jojo! I’m taking my break now.”

“Just clock out this time.” Jojo had near lifetime service to Hardee’s; born with a plastic straw in her mouth, she had been sucking at a peach milkshake ever since. She hauled her greasy-skinned carcass from the back room to cover me, her bleached blond-ossified bangs sprouting out over her navy blue visor. I whisked my visor around backwards and Jonas and I parked ourselves on the foul curb out back beside the dumpsters.

“I heard about you at school yesterday,” he said, holding a vial of bluish-green liquid. “Three guesses.”

“Colored water.”

“No.”

“LSD?”

“No, but I can find some Purple Jesus.”

“I give up.”

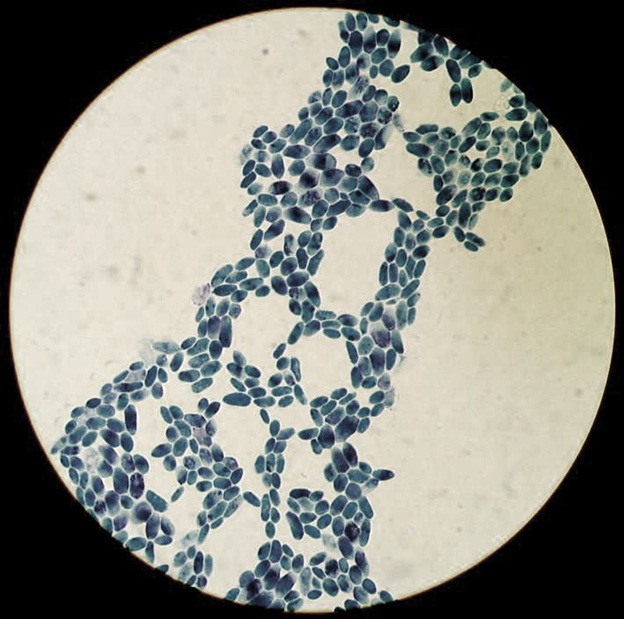

“Methylene blue mixed with phenolphthalein.”

“In English?”

“In English, the methylene blue will make you piss blue for a week and the phenolphthalein will give you the trots.”

“Why would I want to piss blue?”

“Not you, dilrod.” Jonas smiled. “This is your liquid ticket to revenge against Randy Boyles. Your football player claims to bleed blue and gold, right? You think he’d be so proud to piss the school colors, too?”

I grabbed the vial and held it to the sunlight. “How do we get him to take it?”

“They still rally at Hardee’s for the Saturday night parties, don’t they? When he pulls up, put a couple drops of this into his Coke and the rest writes itself.”

“Where’d you get it, anyway?”

“It pays to have a dad who’s head of the chemistry department,” Jonas said. “Come by tonight and tell me how it goes. I’m only here for the weekend, gotta ship back to Andover tomorrow.”

“I’ll see if I can get the car.” My mom had appropriated my Honda hatchback after her car crapped out for the final time. Ever since then we’d arranged an elaborate system of drop-offs and pick-ups—me from school and Hardee’s, her to and from the college. She was the administrative assistant in the chemistry department. She’s the one who delivered updates on Jonas that she received from his proud father.

“Do what you gotta do,” Jonas said. “And don’t forget, just a couple drops’ll do ya.” He left in his parents’ new white Subaru. I tossed the vial in the air and caught it, then slid it into my pocket, where it jangled against some change. Back behind the counter, I adjusted the drive-thru headset like the pro that I was and counted the hours before the town’s Most Valuable Teenagers would arrive.

Every weekend was a rerun of the last. Deep fryers and the amber bubbles rolling up from processed potato sticks, Jojo cracking the whip. As usual we got bombed by seven o’clock. No party began without a gathering in the Hardee’s parking lot. Monster Trucks and Ford Rustangs lined the parking lot, revving their engines and pealing out, squeezing off air horns that played Dixie, the drivers unaware that West Virginia fought for the Union. Kids I saw every school day acted like they didn’t know me, staring across that gulf between their car and the order window.

“Welcome to Hardee’s, please wait.” My mantra.

“May I take your order?”

“Gimme two double cheeseburgers, Frisco burger, large fries, large Coke, and—What do you want, baby?” There was a pause. “A burger and iced tea, unsweet.”

“Thank you,” I said. “Please pull around.”

I opened the window on the moment I was waiting for. Randy Boyles all over again, his baseball cap backwards so you could see all the zits congregated on his forehead. His lips pulled away from his teeth as he spoke. “Hook me up with an extra fries, Pussy.”

“Your total comes to eleven forty-eight.”

“Gimme an extra fries or I’ll beat your ass.”

“Eleven forty-eight,” I said.

“Fries, faggot,” he said, pressing eleven dollars into my hand.

“And forty-eight cents.”

He tossed two quarters at the window. They bounced on the asphalt outside. “Keep the change.”

I shut the window, pulled out the methowhatever blue, uncapped the vial and dribbled some of the mixture into the cup. A couple more drops, just in case. The chemicals disappeared under the fountain. Against my better judgment, I put an extra order of fries in the bag. I didn’t want him coming back. Besides, my mind was swimming in visions of that Cro-Magnon fuck split down the middle. Even after the runs would pass, Boyles would have the Ti-D-Bowl in his bladder for a week.

I opened the window and handed over the drink. Randy attached his lips immediately and took a long slug. I waited for a response.

“You put in those extra fries, fairy?”

I nodded.

“If brains was dynamite,” Randy said, “you wouldn’t have shit for dynamite.”

Randy peeled off and after that the vial of chemicals burned a hole in my pocket for the rest of the rush, begging to go to good use. As the party crowds lapped at the Hardee’s window every football player, redneck, and bubble-brained buttwipe who complained about the service got a dollop of justice. At 9:47 the final drop drained from the vial, and I was only thirteen minutes from finishing the most satisfying shift of my life.

Jonas’s family lived in the middle of Bum-Fuck-Egypt, West Virginia. To get there you drive through a dried-up hamlet of abandoned coal company shacks, and hang a left at the scattering of aluminum-sided mobile homes. This sliver of heaven was where Jonas spent his vacations and the rare weekend, away from the cut lawns and brick buildings of Andover, Massachusetts. When I got there the lights in the main house were already out. Jonas’s parents had turned the family house into a love shack in his absence, so they let him stay in the guesthouse, a hobbit-hole carved into the hillside next to Locust Pond. I tromped through a couple hundred yards of fresh-cut grass, soaking through the duct tape on my Chucks and staining the rubber a wet, dirty green.

“Take off your shoes, man,” Jonas said. “This ain’t your house.”

My socks left moist ovals on the cold tile.

“Socks, too.”

I sat on a knobby wooden stool at a long counter he called the breakfast nook. From the refrigerator he took a glass pitcher filled with an electric blue liquid.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Romulan Ale.”

“The shit Worf drinks?”

“Worf’s a Klingon, idiot.”

“Whatever.”

He poured the Romulan Ale into two highball glasses and plunked tiny spheres of ice into each. He slammed the glass and licked the blue bubbles from his lip. I sniffed the drink and tried not to recoil from the quick bite of alcohol. Slowly I tipped the glass until the sweet nip of Romulan Ale touched my tongue.

“Come on, poseur, take a real swig.”

I swallowed. Iceburn.

“Tickles, doesn’t it?”

“What’s in that shit?”

“Blue Curacao, Bacardi, and Everclear.”

“Everclear?”

“Grain fucking alcohol,” Jonas said. “Drink enough and you’ll go blind.”

“To going blind.” I raised my glass.

“Set up the chess board,” he said.

We chatted and played chess, and by the second game the conversation turned inevitably to ritualized schoolboy pageants of sex and violence.

“You still play soccer?”

“Don’t like team sports,” I said.

“It builds character,” Jonas said, moving his rooks along the same file. “I’m captain of the lacrosse team and the top scoring attackman in Phillips Academy history.”

“There’s a career builder.”

“So you get laid yet?” Jonas asked.

“You haven’t.”

“Course I have.”

“Bullshit.”

“Gretchen Forsythe.” Jonas pushed his king-side pawn. “We studied calculus together. If you could even call it studying. I basically did her homework for her. Night before the final she wanted some extra help, so I snuck her into my room.”

“Go on, liar,” I said. “What happened?”

Jonas made a giant production out of preparing his next move. He wobbled the queen on her axis before sliding her to take my second bishop. He continued as if it was an afterthought. “One thing led to another. Next thing I know her clothes are off, and we’re doing it. Right there on my bed. I was praying the whole time my roommate wouldn’t come home early.”

Fuck him, I thought. But even if it was a fantasy, I couldn’t help but imagine it was me and not Jonas starring in it. Beneath a bookshelf lined in leather-bound volumes I unbutton Gretchen’s blouse. Her blue eyes blink, shy, but not reluctant. She turns off the reading lamp, knocks the calculus textbook to the floor, takes quick breaths as she lays back, placing my hand over her beating heart, over the gold locket she wears round her neck, the full moon’s light over Andover glimmering through a dusting of snowflakes.

Fuck, I thought, maybe it was true.

“Checkmate. Loser sets up.” Jonas drained his drink.

What seemed like hours later I found myself alone on the carpet, the chess pieces scattered around me and the carpet dotted with blue spots. Lying there I started thinking for some reason about the first time Jonas and I ever hung out. I am ten and Jonas eleven; he’s still living in that forest green Victorian on College Avenue. His parents are watching The Crucible at the college, so we have the run of the house and get a little rowdy. Following a couple games of hallway soccer we make Lego fortresses and play Blockade. Simple rules: taking turns, you launch a golf ball at the other’s Legos. Last fortress left standing wins. I have a lucky throw, blowing Jonas’s fortress apart. He gets me in a headlock and then, pinning me on the ground, puts his feet on my shoulders and pulls my wrists with all his might. Only the key turning in the front door saves my shoulders from dislocation.

When I finally stood, I found a glass full of Romulan Ale on the table amidst the rest of the chess pieces. I gulped at the drink, and I threw open the creaking screen door. The air outside was damp and chilly; the moon shone like a flashlight bulb. Jonas stood by the pond tossing rocks, each splash turning the moon’s reflection into wider rings of rippling blueblack.

“Are you okay now?” Jonas said.

“What do you mean?”

“You don’t even remember, do you? You were going nuts. You were punching walls and yelling at Randy Boyles. You took a swing at me, you maniac. I had to take you down. I had to, you know.”

“At you?” I asked. “I don’t even…”

“Don’t worry about it,” Jonas said. “I know you got it rough these days. By the way, I’ll need that vial back.”

I dug in my pocket and pressed it into his hand.

“Empty?” He managed a sly smile. “How much did you give him?”

“About fifteen drops.”

“Fifteen? That’s enough to kill a wooly mammoth.” Jonas squinted. “There must’ve been two hundred drops in there. What happened to the rest?”

“Dosed every jock, hoop, redneck, and douchebag dumb enough to hit the drive-thru.”

“Score.” He slapped me a high five. “The sewers’ll be blue tonight.”

“Imagine the line for the bathroom,” I said. “I bet they’re all crapping their pants right now, staining those tighty-whities a royal blue.”

“Glad you showed some backbone,” Jonas said. “What are you going to do when I’m no longer around to rescue you?”

“Rescue me?”

“You learned a valuable lesson tonight, you gloopy bastard. It’s just like Alex told the Droogs—some get knifed and others do the knifing. You either stand at the top of the stack or you sink to the bottom.” He looked past me up the lawn, to the main house with the lights out in all the windows. “Take my dad,” he said. “He worked hard and now he runs the whole department. Nobody tells him what to do, no one hassles him, and he’s the one calling the shots.”

“What about my mom?” I asked. “She keeps the place running. Without her the chemistry department would fall apart.”

Jonas hurled a rock into the middle of the pond. “So, she’s like duct tape. Is that what you’re saying?”

Tiny waves lapped back on the shore. There were some crickets chirping and the cattails stood still.

“Look,” Jonas said. “No insult, but secretaries are expendable. I’m just saying it’s the boss that has to take action and get the job done. And if I hadn’t have given you that vial, you’d still be cowering from Randy Boyles, and he’d still be punching you instead of you punching the walls.”

Jonas walked back to the house, to start cleaning up my mess, he said. I was still shoeless and waded into the water up to my shins. I plucked a cattail at the base of its stem and whacked at the other reeds until they toppled into the pond. Most lessons are ones you already know: if you’re not the hammer, you’re a nail.

That morning the sunlight raked my eyelashes back. One bewildered moment later I realized I was laying on a futon in the sunroom, under a wall of windows. Jonas frowned as he vacuumed. Then he got down with a rag and worked at the blue stain on the carpet.

“You sure did a number last night,” he said. “Commander of the Grain, that’s what you called yourself. You probably had six shots before you went and wrecked the place Rambo-style.”

I rubbed my right hand. A yellow-rimmed bruise had come up and red cracks cut through the skin on my knuckles.

“What time is it?” I asked.

“Nine.”

“Shit. I gotta get the car back to my mom, so she can get to work.”

“Chill. It’s Sunday; and its spring break at the college.”

“She’s got to work during breaks. She said she has to catch up on things.”

“Well, take your pants then.” Jonas threw a soaked pair of Levi’s onto my chest. “You puked on yourself, you retard. And I’m gonna want those khakis when I come back this summer.”

“I gotta take a piss first,” I said.

Jonas chuckled. “It’ll be blue for a week.”

The mood at school that Monday was more dejected than normal. It felt like the day after a big loss: defeated sighs and a shared humiliation. All the popular kids seemed worn out, as if the pipe-cleaning effects of the methylene blue and phenolphthalein had done to their youthful metabolism what weekends of binge drinking could not. Jonas had left town by then but I’m not sure where he went. I’d found a folded up letter in the pocket of his pants and read it again at the urinal between fifth and sixth period.

Jonas,

Hey you coal-mining hick! Life here fucking sucks as usual. These jet-setting snobs and now I got no down-to-earth motherfucker to laugh at ’em with. I can’t wait to graduate and get out. One more year of this shit, then Brown here I come.

So I’m keeping tabs on Gretchen like you asked and yeah, she’s telling everybody she never went to your room, never even talked to you. She’s saying you copied off her calc exam too. Everyone thinks that’s why you were 86’d. But don’t worry about that lying broad. At least you don’t have to see her trunkass again.

By the way, the new Lacrosse manager we got is some pussy named—get this—Erving. Erv the Perv. No doubt he gets off washing those jock straps. But I guess that’s just another thing you should be happy you don’t have to do anymore.

How’s that comp I made you? Whenever I feel like shit (like every day in this hellhole) I throw on Dinosaur Jr.’s “Freak Scene” and totally rock out. Bradley can’t stand it, I turn it up so loud.

Let me know where you end up going next.–Trevor

p.s. When am I gonna get that C-note I lent you?

I unzipped, stood at the urinal, and wondered who was getting knifed and who was doing the knifing up at Andover. My mom later told me that the office gossip held that Jonas had been sent on to some Prep School down south. Jonas never said another word about his education until he gloated about getting accepted to Columbia.

Randy Boyles walked into the restroom and took the urinal beside me. I crumpled the letter and put it in my pocket. My muscles tightened so I couldn’t pee.

“Goddamn Nattie Lite,” Boyles said over the rush of urine. “Goddamn Nattie Lite, man. We all drank that tainted brew.” He flushed and zipped. “Hayes,” he said, “if you ever fucking grow a pair, you better drink Budweiser.”

Boyles left and I sighed. He had moved on. Never again would I be his target. It could’ve been the peace offering of French fries at Hardee’s, or maybe a less fortunate kid came between him and his girlfriend. Maybe the bout of blue piss knocked some vinegar out of him. Whatever the reason, I never found out why the attention waned, why one minute I was archenemy number one and the next minute I was nothing, not even a blip on the Nerdar, not even important enough for the random noogie or locker cross-check. I felt a tinge of regret that I was a nobody again. But at least I hadn’t been nothing. In my revenge I’d become the source of a rumor that hardened into Rupshire High School myth—the cause of slack sales for Natural Lite that eventually drove the beer off the market in the town of Rupshire—the firmly held belief that “Nattie Lite ain’t worth the fight. Makes ya poo, turns piss blue.”

I unclenched my kegel muscles and let slip a triumphant blue piss.