From the hill, Rory could see over the fields to the farmhouse and parked there in the yard an unfamiliar car, a hunter green Morris Minor with a large black suitcase tied to its top. Mrs. Gillespie sometimes referred lodgers to the Deavitts whenever her guesthouse got full, and Rory mostly welcomed the occasional outsiders and the break they brought from the everyday, everyone aside from the mouthy Americans and the deadened married couples like his parents. But maybe here was someone closer to his age, he thought, from somewhere far beyond the monotony of Ballinshere. He cleared the distance between the fields and farmhouse in minutes, not even stopping to wash at the water pump.

Rory hesitated at the back door, hearing a rare excitement in his father’s talk and the voice of this new visitor, soft in tone and the accent posh, from some choice part of Dublin. She thanked Rory’s parents for agreeing to accommodate her, and Rory’s father passed off the gratitude with an exaggerated laugh. Perhaps he’d opened a bottle of Powers for the guest, someone special so.

Rory scraped the muck from his Wellingtons on the steel doormat and entered the kitchen, stopping still when he saw her. There, at their scarred kitchen table, sat the most striking woman he’d ever encountered in the flesh. She looked to be older, mid-thirties maybe, with long black hair and a creamy, soft-boned face. The woman stopped mid-sentence and smiled at him, to which Rory could only blush and sputter a half-intelligible greeting. His mother sat opposite the woman, her expression hardening as Rory’s cheeks filled with heat.

“Don’t just stand there, Rory, fetch Mrs. Moore’s things from her car.”

“Please,” she said, “call me Ashling.”

Her smile found him again.

Rory hauled the third and largest suitcase upstairs, conscious of Ashling climbing the steps behind him, the case heavy enough to hold all of his possessions put together. He tested her name silently, Ashling—the soft start of it and the little flick of the tongue at the end. The name meant ‘dream’ if he remembered his Gaeilge well enough. Not that he’d had much learning, his parents having pulled him from school two years ago so he could work the farm full-time. It was something he’d never minded much until now, when he wanted to draw out the words necessary to impress her.

Rory moved from the stairs and onto the landing, almost falling under the case’s weight. He thought he heard Ashling snicker as they entered the guest bedroom and his cheeks blazed again.

“I’m sorry the cases are so heavy,” she said, moving to the room’s only window and letting in the malicious breeze and the stink of the silage. “It’s really so beautiful here.”

“You think?” said Rory.

She glanced at him quizzically then returned to the view. Alone with her in the small room, Rory felt especially self-conscious—his pimples bigger and whiter, his cow’s lick ridiculous and stockinged feet too small. His big toe peeked through his threadbare sock, the nail yellowed. Worse, he smelled of hay, sweat, cigarettes and cow shite. No matter how hard he scrubbed, there would always be that stink of the farm on him. If she asked, he’d say he was eighteen.

“Thank you for your help,” she said, her attention already on unpacking. From her largest suitcase she removed a checkered wooden case finished with a shiny lacquer and held together with bright brass hinges. “Do you play chess?” she asked.

Rory swallowed a childish impulse to mention his skill at checkers. He shook his head.

“I can teach you if you like?”

“You must be planning on staying a while so.”

“I’m not in any hurry anywhere, no.”

She unlatched the case and removed an assortment of gleaming chess pieces sculpted from blond and black woods. Her work, she explained, hand-carved from ancient bog oak. She gave him a few to examine—a castle and horse, and the crowned king with a finial at the tip that reminded Rory of a beggar’s cupped hand. The horse, he noticed, even had teeth—tiny notches dividing each one. He fought the urge to pocket it.

“That’s the knight, an important piece,” she said. “You really should learn; it’s a fascinating game.”

He held the knight a moment longer in his large, dirty hand before dropping it to the bedspread.

“You don’t seem enticed,” she said. “What interests you then?”

“I dunno, really. I’m not one for making things, that’s for sure.”

She picked up a blond pawn. “Well, I don’t think of myself as making them. It’s as if they’re already there in the wood—when I carve, all I do is set them free.”

A waft of cow shite blew through the open window as she spoke. With eyes glazed she stared at the piece in her hands, a world away, thought Rory, even as she was right there in the room with him. Is this how he appeared to people—not at all? Rory felt the blood leave his face and like a fool checked the carpet at his feet, half-expecting to see a stain.

“Are you all right?” she asked, suddenly herself again.

“Why wouldn’t I be?”

He looked down again at the carpet, sorry for his sharp words. Ashling resumed unpacking and in the stretch of silence that followed Rory’s nerves got the better of him. At the doorway he reminded her his mother would have dinner ready shortly.

“She’s not one to be kept waiting,” he said.

In the shower Rory raked his fingernails over his body with especial vigor, digging into his armpits, groin, and the crack of his arse. He dressed in his best and hurried downstairs to the kitchen, where his mother looked him over with narrowed eyes and her lips pushed into a sour nub, an expression that scarcely cracked even as Ashling entered the room.

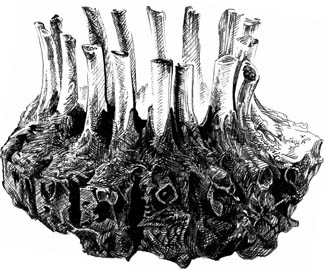

“We’re having lamb,” she said.