“It’s never easy meeting a complete stranger, especially one as beautiful as you, without being properly introduced, but shall we try anyway?” (Eagan, 201)

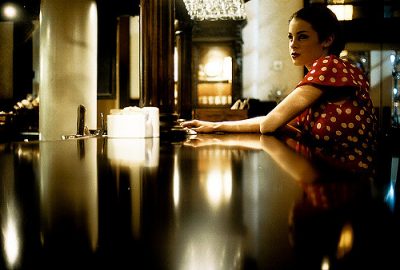

An emo band is blasting onstage and there’s this beautiful woman across the bar, wearing a cocktail dress and gold hoop earrings. Her hair is dark red, a different shade from my soon-to-be ex-wife’s.

I am an irresistible sex machine.

I go and feed her the line. She just blinks. The guilt and self-hate ball up in my stomach, but I keep it down, away from my face.

“What?” she says.

I say the line again, trimming some of the modifiers because the emo band is now caterwauling. She leans close to my ear.

“Um,” she says, rattling my eardrum, “I guess.”

I buy us vodka tonics even though she’s not quite done with hers.

“Do you like this band?” I scream.

“No!” she shrieks back.

The place is popular, new, and people keep bumping into me. I can smell everyone’s shampoo and cologne.

I say, “After these drinks let’s get out of here.”

She nods, finishes her first drink, and starts the one I bought for her. Big freckles line her arms and she has fine, soft hairs—nothing like my ex-wife. Patty grows no hair on her arms, is so afraid of the sun and more freckles that she cakes herself with sunblock every day. When I did the laundry her shirts always smelled like the beach.

The beautiful woman and I sit on stools, not really saying anything, not just because of the noise but also because speech might make us think more darkly of ourselves. She looks down, touches the screen of her smartphone. I have a dumb phone. Her phone makes me feel empty and inadequate inside. When she goes to the bathroom, I realize I haven’t even asked her name.

The band crashes and bashes through their loudest songs for the finale. The strobes flash and people up front lose themselves in the spectacle, but back here we are missing the point of it all.

The beautiful no-name woman doesn’t return. The band throws guitar picks and drumsticks at the crowd. I finish our drinks.

“Hi, a beautiful woman like you should have a great evening, give me a chance to let that happen. May I join you in a drink?” (Ibid.)

In a drink, I think. Why in a drink? I sit at the bar and can’t get it out of my skull. It’s as if I’m asking the beautiful woman to step with me into a Jacuzzi-sized martini glass. I think about how John Eagan, author of How to Pick Up Beautiful Women, puts B.A. after his name on the cover of his book. I have an M.A. and teach composition at Southeastern State Community College. The grammar in Eagan’s pickup line is wrong, wrong like my life.

After a few vodka tonics, two blonds and a brunette walk in and take a booth. I look around and a couple guys, one in a plaid sportcoat and the other swaying drunkenly on a stool, instantly bird-dog these girls. I decide to act. According to Harville Hendrix, Ph.D., author of Keeping the Love You Find, I must work on my action. I’ve got thought and feeling down. It’s sensing and action I need to work on, so I’m across that room like a spider monkey on angel dust.

According to Eagan, when there are several women, you must buy them all drinks. It costs, but so does life. You’ll lose more money than drink money in your life, especially on something like a divorce.

I deliver the first sentence of the line. Then I say, “May I join you for a drink?”

They look at each other and laugh. I’ve got a new black dress shirt tucked into my jeans. Chest poked out, shined leather shoes. I know I look good. I am a sex machine.

“Are you buying?” asks the one I want, her lips shiny with gloss, her pushup bra displaying gravity-defying cleavage. Like the bras Patty bought from Victoria Secret, the ones that could not help her.

“Of course,” I say.

They giggle in unison.

“Sit,” she says, and offers her hand. Her name is Marley. “My mom liked reggae,” she says. “A lot.”

Marley’s hair springs from her scalp in long, tight braids. She’s a nurse at the children’s hospital but wants to be an actress. In fact, she’s acting in a few plays across town. She aims her body at me when she speaks. It’s a good night to be alive, in the company of beautiful women.

Her blond friends, Sidney and Keeley, go sit at the bar where other men buy them drinks.

“You have great friends,” I say. “That says a lot about you.”

“So where are your friends?”

I consider this. “I’m losing most of them in the divorce.”

Then I have to do a lot of talking. I talk about the separation and Patty sleeping with her boss. I don’t talk about the heartbreak and the loneliness. That pain belongs to me alone and, besides, I want to have a good time. Marley’s body language never closes up. She listens. I think maybe there’s hope out here in the world. Maybe there’s life after losing so much.

Pretty soon her friends want to go. It’s late. They work early in the morning. There’s a long drive home. There are a million reasons to say goodbye to the night.

“Give me your number.”

“No,” she says. “Give me yours.” As she puts my number in her phone, I ask her why. “I don’t date married men,” she says. “But we can be friends.”

The wind gushes out of my lungs. I hang in there, though, smile on face, showing the teeth.

We shake hands goodnight. In that dress, from behind, honest to god, she looks like a violin, a Stradivarius, a work of art. Another beautiful woman walks out of my life.

“I’m not trying to be rude or impolite, or invade your space in any way. I just wanted to know if a lovely girl like you can use some pleasant company?” (Ibid.)

I have fifteen-minute conferences with students about their personal narratives. The author of the narrative about a highway patrolman carrying nunchuks walks in. She has curves I’ve never seen in class because, until now, they’ve been hidden beneath ballooning t-shirts. She’s made up her face and is wearing a low-cut top.

I smell a setup.

But wait!

Maybe she’s my Imago, Dr. Harville Hendrix’s word for my romantic match. Maybe she can help me resolve conflicts with my parents and how they fell apart. Maybe it’s only incidental that she’s my student and I’m her instructor. More mysterious things have happened in the world, have they not?

I look at her paper and ask about the nunchuks. She giggles and flushes red. “I have to be honest,” she says. “I made that up.” She leans forward so I can look at the goods. I don’t. Or at least I’m not obvious about it.

“Well,” I say, “it’s good writing, but I don’t believe it.”

“You don’t think the nunchuks add tension?” She pulls out her notebook, licks her fingers and starts turning pages, red nails on white paper. “Because, Mr. Little, you told us last week that every narrative needs tension.”

I go into my lecture voice and tell her it is the right detail in the right place, blah, blah, blah, that makes a good narrative. While I talk, she unsheathes a lollipop and wraps her lips around it, pushes and turns it against her tongue. In this moment, I realize I have been visiting too many porn sites and my sex drive is off the charts. Those images burn into the crevices of your brain, by the way. At the end of my screed I’m almost babbling, but she isn’t listening anyway.

“And that’s why nunchuks has to go,” I say.

She replies, “I’ll do whatever you want, Mr. Little.” She crunches down on the red lollipop.

I realize she has said my line to me with her eyes and body and I am the one being picked up. This beautiful woman knows a sex machine when she sees one. She understands that I am worthy of love.

“Hi, I just wanted to tell you that what you are wearing looks stunning on you. May I join you?” (Ibid.)

This beautiful girl is at the coffee shop, wearing a tank top and jeans, nothing I would call stunning. She’s got big green eyes, nothing like Patty’s brown ones. At this crucial moment, Patty calls me. We’re trying to be friends, but I no longer like her.

“Will, we need to talk,” she says.

“About what?”

“Everything.”

“I don’t want to talk about everything,” I say. “Life is short.”

“Connie says you’re out every night going to bars. Do you have any idea how sad that is?”

Constance is Patty’s best friend who also lurks at the law firm. Phil Grill’s law firm. Grill and Sprinkle, Attorneys at Law. Those are action names. My last name is Little, an overused adjective. I wrack my brain but don’t remember seeing Constance anywhere. Perhaps it’s because she’s not a beautiful woman.

I say to Patty, “Do you know how sad it is for a forty-year-old born-again virgin to go to bars and be up in my business?”

“Don’t make fun of Connie,” she says. “She’s only looking out for you.”

Blood rushes to my face. I think of Patty sprawled on Phil Grill’s desk, white garters on her thighs, though, to my knowledge, she’s never worn such undergarments.

“Was she looking out for me when I would call for you? Was she looking out for me when she would lie and say you were in a meeting?”

Silence.

“You’re changing the subject,” she says.

I hang up. She calls back. I press reject and erase the voicemail without listening to it.

The girl with the big green eyes is still waiting. I hold the words of the pickup line in my mouth, tapping them against my teeth. When I begin to move, a man in overalls slips into her booth and grabs her hand.

Stunning, I think.

“I was intrigued by your beauty and grace, and I just couldn’t keep myself from coming over. May I join you in a drink?” (Eagan, 202)

Nunchuks and I schedule a special midnight study session, with drinks. She gets dressed and we shake hands like it’s business. She opens my office door to go.

“Listen,” she says, “I’m going to be out of town for the rest of the semester. Do you think you could use your knack for detail and specificity to imagine my future papers into existence? I’d appreciate it.”

I look out the window. Not even the stars can watch this.

“Oh,” she says, smacking the back pocket of her jeans for emphasis, “and it’s A for ass.”

Her heels snap down the long empty hallway.

“Hi, I’ve seen that king [sic] of dress on other women, but none of them looked as great as you do in it. Do you mind if I join you?” (Ibid.)

A typo? Are you kidding me? These are the most important words of a three-hundred-page book, and he decides to misspell one of them. I begin to wonder if I’ve taught Eagan, if he’s been in one of my composition classes, writing it’s for its, then for than, effect for affect, accept for except, lose for loose, quite for quiet, and there for their and they’re.

I go to the club in search of the king of dress. She is nowhere. My imagination is too blank to conjure her. My hand picks a bottle of Wild Turkey from behind the bar. I stand in the alley with it before great darkness descends and wipes my memory for a few hours.

Next thing I know, cars line the curbs along both sides of the street. In the blinding porch light, silhouettes hold solo cups. People talk loudly in drunken deafness and stare at me as I stumble up the sidewalk. I don’t recognize any of the shadowed faces but keep moving toward the front door as if I have some purpose in this world.

A clutch of drunks on soiled couches in the living room, tapestries on the walls and sheets over the windows, CDs and DVDs spread on the floor beneath the TV like humdrum offerings. I find the keg in the kitchen where a tall drunk kid in a baseball cap offers me a yellow cup from a stack. He pumps the tap and ice water rattles in the garbage can as I aim the spout.

I kick aside some trash and go out onto the back porch where a bare bulb illuminates gray decking and a few feet of grass beyond it. There is nothing out here but squirrels and birds huddling in the live oaks. The back door opens and out comes a powerfully built kid with another bottle of whiskey. He has on a tight undershirt and jeans, no shoes. Someone has smeared lipstick on his face. He passes me the bottle without speaking. I take it, unscrew, drink, re-screw, and pass it back.

He nods. “What’s your name?”

I’ve been reading Shakespeare. “Falstaff,” I say.

He laughs and passes me the bottle again. “Whatever.”

When I pass it back he sets it on the rail and pulls a smartphone from his pocket. A pale, blue light shines on his face. It’s an expensive one, with internet and everything the world has to offer. He can use it to check out of life whenever it bores him. I think of Patty scrolling through sexts and emails from Phil Grill, big smile on her face. Scrolling and smiling, treacherous and banal.

In the light, his jawline is illuminated distinctly. My first instinct was thinking, but I’m sure this is the time for action. He is too preoccupied to see me rear back and take aim. I miss his face completely, fall and bang my head down the steps into the yard, my feet catching at the top, soles skyward. I remain conscious long enough to hear the entire house party come to the rail and laugh.

“As I was standing there, I noticed how beautiful you were. I thought perhaps we could spend our time more agreeable together. May I join you?” (Ibid.)

Were instead of are, as if beauty fades with time, which is not what you want a beautiful woman to think about when you are trying to enter her life. You don’t want her thinking about death the way you do. That’s no way to find your Imago.

Ice in a ziplock bag against my swollen head. My skull isn’t broken, but an enormous broken-blood-vessel bruise at the temple lopsides my face. The pain of it almost makes me forget my hangover. As it loops in my head, Eagan’s our time more agreeable sounds like poetry.

The house smells like last night’s chicken bucket. I click an email from the chair of my department. It seems Nunchuks has been arrested for drug-running in El Paso. Her parents are furious. The chair would like me to come in immediately to explain how Nunchuks has maintained her stellar average from such geographical distance.

I get dressed and make myself presentable if presentable means looking less like a corpse. I smile in the mirror. Somehow all teeth are still present.

The sun beats through my sunglasses. I manage to get out of the car, through the parking lot, and into the building without vomiting. The chair’s office door is wide open. Her assistant waves me in like an air-traffic controller.

“William,” the chair says, getting up, her face clouding with concern. “Are you under the weather?”

She’s wearing a cream-colored blouse and rouge on her cheeks. For a split second, I think about my Imago and how perhaps I’ve been looking at this meeting all wrong. Maybe this is the time for pickup lines. I try my own.

“I’m just fine, Ruth. You’re looking lovely today.”

She nods and sits, so I do the same.

“I know you’ve been going through some trouble lately. Of course, I heard about Patty. But this is something else altogether.”

She tells me Nunchuks’ father is a big donor and that the provost has spoken and now is the time is for decisive action. My contract won’t be renewed. I’ll be relieved of my classes and have to adjunct elsewhere. Everyone is very sorry for these unfortunate circumstances.

I start zoning out, thinking about life and my place in it. There’s a pause and I realize she’s expecting me to respond.

I say, “I thought we might spend our time more agreeable.”

“I’ve never really said this to anyone before, but I just felt I had to tell you—you’re the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen.” (Ibid.)

I should stay home, but there’s this voice inside saying whatever will fix my life is not at my house. The fix isn’t inside me, either. It’s out there, running through magical fields with the beautiful women.

Down by the beach there’s an old bar where tourists flock for the holiest of Gulf Coast holidays, Spring Break. Luckily it’s the offseason and there’s time and space to think. I go out looking for the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen. I don’t want to lie, so she at least has to be in the ballpark of the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen. Maybe just in the same zip code.

The place serves crab. There’s a constant fishy odor and the reek of beer-soaked floorboards. The one woman in the bar is wearing a strapless linen dress with turquoise bikini straps on her browned shoulders. I sit down next to her and see that her face is lined from decades spent sunning. But, yes, it is quite possible that twenty years ago she would’ve been the most beautiful woman I have ever seen.

For a moment, I don’t think I can go through with this but I snap out of it. This is what single people do: they deliver the lines. I give it to her and she smiles, she absolutely beams at me. I’m instantly sorry that I have stolen the line from Casanova, B.A. and that I couldn’t make her smile by my own wit.

Turns out she is a good person, with ideas, a heart, and a mind of her own. On her smartphone, she shows me pictures of her children and it doesn’t make me feel inadequate. They are in college, smiling, happy. She tells me that their father is no longer with us. I don’t pry. Death is not the path to sex.

I tell her about my ex and how she wronged me. I tell her I’m still doing the job I lost. I talk about how I’ve been going to the gym to stay sane and get my body together. I’m not fit, just gaunt with stringy muscles, but I offer my knobby biceps to feel, my budding, angular pecs.

“Wow!” she says, genuinely impressed. “So strong! So full of life!”

After laying hands on me, she doesn’t take them off again. She squeezes my knee when she’s telling a story. She touches my shoulder when she laughs. It almost creeps me out, but I understand she’s taking action.

When we leave the crab place we are hot for each other in the alley. Our hands are wandering, searching for the parts that will stave off the loneliness. Her place is close, on the beach, but we drive my car to get there faster. I think maybe all this work, this devotion to and study of beautiful women will finally pay off. Someone will appreciate and validate who and what I am. I am more than an ex-composition instructor. I am a sex machine.

Inside her condo the first thing I notice is the mechanical hiss. She tries to kiss and moan over it. She is telling me how incredible I am, how special and kind. She won’t flip on lights and is trying to pull me down the hall. But I feel the switch digging into my shoulder blade and flick it. There, in the dining room, is her husband, a husk of a man hooked to tubes, tanks, and a breathing machine. He is preserved by the respirator, yet lifeless as a dining room table.

She sees the look of horror on my face. Her mouth starts shaping words a few seconds before anything comes out.

“Don’t go,” she says.

“I really should,” I say.

“No, you shouldn’t.” Her eyes are wide and electric with longing. “It’s okay. Stay here with me.”

The hissing fills the space between us. We try to hold our breaths but the machine breathes for both of us. There are people lonelier than we are. There are lives more ragged and actions more desperate than anything Harville Hendrix could imagine. There’s no pick-up line for this.

She places my hand over her heart. She holds it there, almost trembling.

Lonesome is a world.