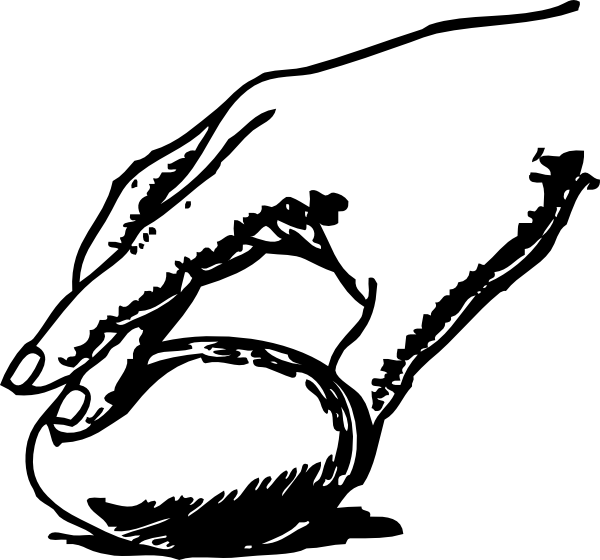

I cracked the eggs one-handed. I was whipping them with a fork when I saw her in the doorway, rubbing her eyes, dragging her stuffed rabbit.

“What you doing?”

“Making scrambled chicken abortion.” Her mom hated it when I said things like that.

“What’s chicken potion?”

“Scrambled eggs, kiddo.”

She looked at me, her hand still held up next to her face where she’d forgotten it. Four must be a wonderful age. I wish I could remember it. She looked down at her rabbit.

“Are you hungry, honey?”

“No.”

“Is Mr. Toots hungry?”

She shook her head and gave me a patronizing look she’d inherited from her mom. She had that same impossibly blonde hair. I finished scrambling the eggs in the bowl and stuck it in the microwave. I pushed some buttons until it said three minutes and hit start. The clock flashed 3:00 PM. Only Kasey knew how to use the thing. I tried again.

“I’m sleepy.”

“Go back to bed then. It’s too late for you to be up anyway.” The microwave had been about twelve hours wrong.

“I want mommy.”

“She’s still at work, kiddo. She’ll be here in the morning when you wake up.”

“I wanna go see her. Eat at her restaurant.” The word came out west-want.

We’d told her that Kasey waitressed. We talked about it a lot, trying to figure something out. I wanted to be honest with her. Kasey said she was too young to understand. I said that was why honesty wouldn’t hurt anything. Kasey said what about later. I said it wouldn’t matter. We decided to say mommy was a waitress, for a place that was only open at night. Four, for all its sweetness, is an awfully gullible age.

“We can’t honey, they only allow grownups.”

“Why?”

“It’s a grownup thing, sweetie. Don’t worry about it. Go back to bed.”

“I want eggs.”

The microwave went off. I took the eggs out, broke them up and gave her the small portion. We sat across the little table from one another. She didn’t finish. Head nodding, eyes lidded, she dropped her fork. I put Mr. Toots under my arm and picked her up. She opened her eyes partway as I walked to her room. I told her to go back to sleep.

“Can I stay up till mommy comes home?”

I thought about saying yes. Letting her try, because Kasey would be home soon. It was a bad idea. Four year olds, even I knew, need their sleep.

“No, sweetie. You need to sleep.”

“Please, daddy.”

“Not tonight, little lady.”

“Fine,” she tried to look pouty, but her eyes were closing again.

I tucked her and her rabbit into bed and pulled the covers up to her chin. I wished she hadn’t called me daddy. I loved her, but that still felt wrong. I looked at myself in the hall mirror as I walked back to the kitchen. I wasn’t a daddy.

I poured myself another cup of coffee. In the living room I flicked on the TV and immediately had to crank the volume down. There was a cable news show on talking about how god-awful everything had gotten. I looked at the pile of bills on the coffee table. News was never new. It just ground on like breakfast-diner conversation.

My mother had called a few days before. She’d seen me on the evening news. Me at fifty, she said, just laid off from a job making cabinets after eighteen years. The guy had said he hadn’t really liked the job, but it had paid the bills so he did it. He sounded so defeated, she said, and he looked just like me, only grayer and more tired. She was scared I’d do that, take some time-server job and end up like that guy. I tried to reassure her that if I was going to do that I already would have, and we wouldn’t have had to borrow that money.

I could only take so much of the news. I already knew about the economy. I looked at the clock; Kasey would be home soon and we could go to bed. I liked to wait up for her because I didn’t sleep much anyway. But this time I was actually tired for once. I fought it some—flipping through the channels only half-watching. My eyelids drifted and somewhere the gray-blue haze of television and sleep blended into each other. I saw myself reflected in a window, hard lines around my eyes. The gray edges of my hair framed a smiling face more worn than I remembered it. My hands moved cleanly across a piece of wood, the warm, finished grain smooth beneath my fingers. Kasey’s hand reached out and laid on top mine. I looked up to her face, the laugh lines around her mouth I didn’t remember. We stood, surrounded by construction mess, in a half-finished kitchen. Hammering from behind, and I turned and saw the man my mom had talked about. As I’d imagined he looked nothing like me. His eyes met mine and looked away to Kasey. His mouth soured, like he was working out a bad taste. Her hand tight on mine, I felt Kasey against my back and we watched the man return to the cabinet installation. Even inside the dream I could tell the rhythmic fall of his hammer was a desperate wall between himself and our joy.

The pounding woke me, alone in the living room. There was no hammer, only someone pounding on the front door. The TV was still on and flickering, filling the room with blue and quiet noise. I found my glasses and the door pounded again. It was late. Early. Almost time for the sun to be up. Maybe Kasey had come home already and hadn’t bothered to invite me to bed. I wondered what I’d done this time. More pounding as I stumbled to the door. Whoever was out there pounding at this hour was really going to get it. Waking the kiddo, waking Kasey, didn’t fly.

I opened the door and the cold rushed in. I drew the air into my lungs to ream this prick, but the prick wasn’t alone. There were two of them. Not pricks. These men looked at me flatly and with pity. The younger one looked a little scared. They took off their hats; their badges reflected what little light there was. My legs turned to rubber. Four years old isn’t old enough for this, was all I could think. They asked if they could come in.