It’s raining like a movie, and Stevenage bus station has no buses, just me and Salvation Army Bloke in his raincoat and wet hat with red ribbon, probably waiting for a bus to heaven, which he won’t get from the SB2 stop, ‘cos that goes to Oaks Cross Crematorium, which is kind of the opposite. I should tell him that, but instead I’m thinking about my parents being dead and what it’s like to be a teenage orphan—a quarter bottle o’ whisky, endless rain, and a long road ahead. Salvation Army Bloke approaches, I’m jealous of his red ribboned hat. I tell him about both my parents being dead, he tells me the good news, that Jesus was an orphan too… sort of. I quiz him about God being Jesus’s dad, and he says the good news, is that’s a metaphor, I don’t know what a metaphor is, I nod like I’m picking up on the affinity with Jesus thing and ask to try on his hat and he says I can’t. Then, confusing for Salvation Army Bloke, Mum pulls up in the car because no buses are running in this rain. As we drive off, Mum asks why I called her Auntie Mavis, I tell her I was thinking on my feet.

At school, the caretaker’s left his ladder out so I climb up it and wander around the roof, planning to chuck tiles off at the headmaster, get photographed for the Stevenage Gazette then get sent to a remand home. But no one sees me and I can’t find any roof tiles. Instead, I contemplate my burning love for Sharon O’Shaughnessy, she thinks my poems are weird and I’m a weirdo, but you can’t turn your back on love. My poems were weird—I rhymed Sharon with baron. These were the challenges for an imaginative fourteen-year-old, undead parents, unrequited love, and finding rhymes for Sharon. That and how to get down off the roof now the caretaker’s taken the ladder away so Mum has to come to school and have a “chat” with Miss Wilson about me. “It’s becoming a habit,” Mum says mysteriously. Looking back, maybe it wasn’t so mysterious.

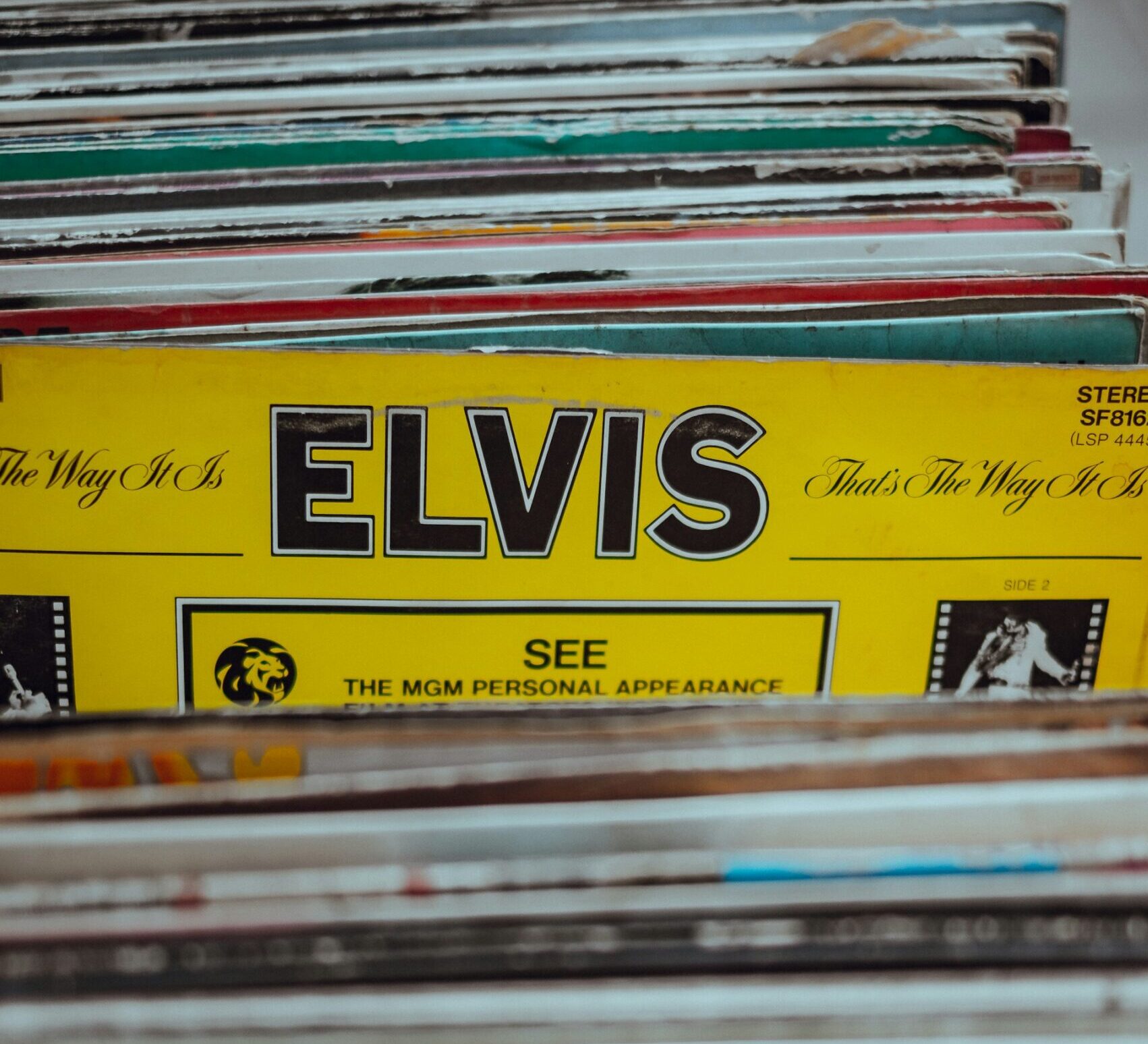

I record every song from every Elvis film on TV, and my shoe box cassette recorder is ready for more. No one is allowed into the sitting-room when my Elvis recording is in progress, my sister tried once, and her thumb is still a bit wonky from where I slammed it in the door. I press Play and Record. Elvis sings. He’s singing to me. Straight into my soul. He knows all about Sharon, how shit school is, how tough it is being a weirdo, with a brain exploding with new ideas, like burying pennies in the vegetable garden and digging them up a year later when they’re worth thousands of pounds as treasure. Elvis knows, and I know, that our friendship is our destiny. When Mr Freeman rails at me for having my tie on wrong, I think, “What would Elvis say?”

“Ain’t the tie that’s wrong sir, it’s the world out there.” Another detention.

I linger in the woods by the school gate, Sharon’s gate. She’s approaching with Angie Evans, Elvis gives me a friendly shove forward.

“Hi Sharon.” I’m casual and well-rehearsed. “You wanna take in a movie, go for a cruise, on the bike?” Elvis gives a thumbs up from the woods.

”What bike?” says Sharon, not going with the flow. Good job love is blind.

“It’s a motorbike. A BSA.” I don’t have a motorbike, but fake it to make it.

“BSA—like Bull Shit Again,” says Angie, which is sharp for a girl in the C stream for English. They giggle. “Weirdo,” says Angie as they walk away. Then… Sharon turns, looking back in slow motion. She sees me astride my BSA, leather jacket and revving engine. Elvis says, “Ain’t no mistaking that look, son.” We roar off on our bikes, Elvis with his guitar slung over a shoulder, we’ll end up in some Vegas bar, have a few whiskeys do a few songs together, Sharon’ll be there, with a look that says, I always loved you, you know that right?

I never told my dad that Elvis was my real dad, it would be too upsetting for him. He’ll find out when Elvis comes to Stevenage, to haul me out this no-hope-town and take me home to Graceland. No more Lego houses and yellow buses and stupid fountain in the town centre, that we poured washing-up liquid into, bubbles overflowing everywhere, so they closed the town centre until they “ascertained the issue,” and the old newsagent where Sharon had a Saturday job, and the freezer centre, four shops down, where I had my Saturday job, and the industrial centre where we all got apprenticeships a few years later, and the bank where Sharon eventually got a job until she married Phil Richards of all people, and had babies and got leukemia and died at forty.

That summer, early Tuesday morning, my parents come into my room. Unusual—Martians in the town centre, meteorite’s trashed the school, tsunami disaster in the boating lake? They don’t speak. They leave the morning paper beside my bed. It sits there with its headline—“Elvis Is Dead.”

I think about tidying my room. I look at the life size poster on my door.

“Is this true,” I ask Elvis, in his gold suit.

“Sorry kid,” he says sympathetically.

“You’ve really let me down Elvis.”

The good news—it’s not true. Because years later when me and Angie get married at the Little White Chapel in Vegas, we book Elvis for the wedding, and he sings Viva Las Vegas wearing that same gold suit. Thanks Elvis. Thanks for everything.