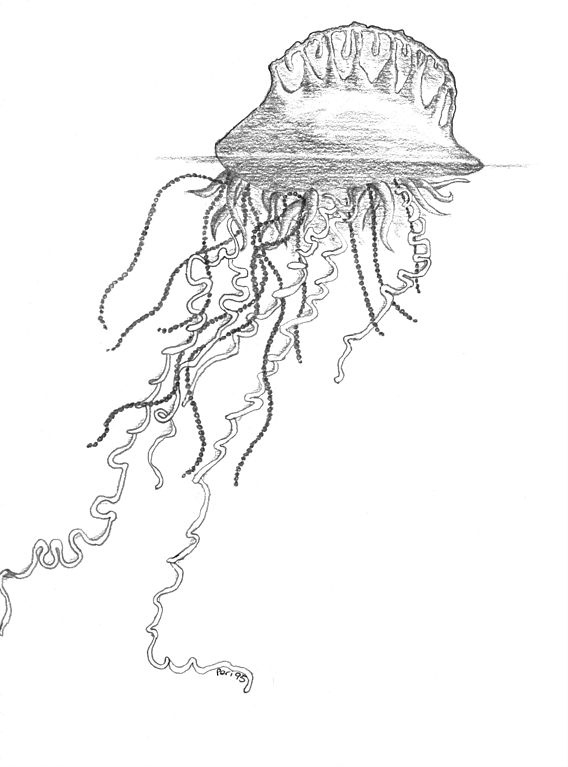

The Cane Palace brochure said nothing about swarms of Portuguese Man of War in the waters of their very expensive private beach. Yet there was the official sign, posted not ten feet from where Ray Ryan interrogated the towel boy. “Your sign says Portuguese Man of War hazard December through May,” he said. “So what are those people doing out there?”

The towel boy kept on folding, kept on setting out the bottles of Cane Palace water and the little paper cups of complimentary sunscreen. Ray thought he looked odd performing these fey activities because he was cut like a linebacker. He read the boy’s behavior as sullen, like he didn’t consider the question worth answering. “Your sign,” Ray said, pointing. “What does it mean? Is it correct?”

“The sign is correct,” the towel boy said, his native island face blank as the sand.

“Right now,” Ray said. “Are there jellyfish out there or not?”

The towel boy’s shrug was unreadable, and so was his answer: “I don’t know.”

Ray marched back to the beach after lunch and what he saw made him boil. So many guests dunking, dipping, dogpaddling, standing waist-high and chatting—the cove could have been a public bath in Tokyo. By now the towel boy had been joined by his buds, four fellow islanders. All of them were smartly turned out in crisp khaki shorts and cucumber green polos with the Cane Island logo, the ubiquitous stalks of sugarcane. Together they seemed like a clique of junior bodybuilders, or bodyguards for some Asian film star. Two of them had Tarzan manes. Their tattoos were cryptic in that South Pacific way, endlessly winding and tangling, like tentacles sent from the bottom of the sea to guard warrior muscles.

The next morning Ray strode up to the lobby desk, eager to find a hike with enough ups and downs to maybe keep the waistline from swelling into yet another belt-hole. Behind the desk the girl was attired in the female version of what the buff beach attendants wore: the crisp khaki and cucumber green, the same sugar cane graphic on everything from cocktail napkins to cabana umbrellas. She was an island girl who registered indifference, or diffidence, or whatever it was that hit Ray like dry ice, in the very act of smiling for him.

While she fished in her desk for a trail map Ray looked around at the murals all over the big room, centuries-old depictions of the early South Pacific war parties who’d fought their way onto Cane Island and populated it to this day. The murals showed how they’d paddled their outriggers an astounding distance, some twenty five hundred miles of ocean, coming from God knows where. Yet at journey’s end they still had the strength to spill onto the shore and hack the existing inhabitants to pieces. Fierce as these originals were, they fell like swatted flies at the onset of the nineteenth century, when the Western sugar tycoons rolled in. The natives were crushed and chained, and their machete skills turned—under the lash—to the usual Caucasian-glorifying pursuits, foremost of which was building the plantation manor house known as Cane Palace. Back then it was the domain of hard white-faced masters, now it was the domain of soft white-faced guests. Tippers extraordinaire. The present Cane Palace, touted in high roller magazines like The Robb Report, was a five-star resort owned by Swiss luxury hoteliers, but largely staffed with island folk. “Swiss-trained and efficient as a Swiss clock,” The Robb Report crooned.

The desk girl unfolded a piece of glossy paper and spread it on the counter, which was an enormous plank of hand-hewn jungle-wood, black as the lava that lined the seacoast. Before she said even a word Ray saw there were only three trails mapped out, each highlighted in cucumber green. One was hardly more than a walk beside the beach past the towel boy and the Man of War sign. Another followed the cart paths on and off the pristine golf course. A third snaked along the ocean on the side of the property that seemed to have no Cane Palace beaches, pools, bungalows or facilities of any kind.

“What about that one?” Ray said, emphatically pressing his finger on the map.

Either the girl didn’t hear his question or she ignored it, responding in a kind of teleprompter voice that seemed flat and faraway, the kind of apathy heard from the other end of some vast fiber-optic sprawl. The only difference was that her inscrutable face was right here, two feet in front of his. In her tech-support voice she droned on, like some robot-concierge, trying to get him to choose the beach or golf course trails because they had shade trees and were prettier walks. “That’s the problem,” he snapped back. “They’re walks, and I don’t want a walk. I’m fat. I want a hike.”

“The trail is all overgrown,” she said. “No one goes there much.”

“Sounds perfect,” Ray said.

A half hour later that was the trail he was on, scaling the wave-battered lava chunks in his new hiking sandals, a bottle of Cane Palace water stuffed in the cargo pocket of his baggy shorts. The more the desk girl had discouraged it, the more he hankered to spite her and go. Based on the beach experience, the first thing he had expected to find was a herd of other hikers, but as Ray approached the top of the first rise he felt a rush of solitude, the sense that he was as alone as a man on the moon – and the crazy shapes of the lava made him feel like he was on some moon.

Decidely un-lunar, however, was the gathering heat. The morning sun was on the move along with him, and it rose faster than his fat hiker’s feet. But it was good, he told himself. Double action on the blubber roll: If the trail couldn’t walk it off, the sky would broil it off. Ray sucked from his water bottle and was in the middle of a foot-hand rock scramble when he found a monster root humped across the trail. He palmed the spur jutting out of a black crag and hoisted himself. But the spur bit his palm like pins and needles – a far cry from familiar New Hampshire granite, this spiky lava – and he let go fast and swung his thigh over the root instead.

The effort was worth it. He stood on a promontory that gave him a jeweler’s view of the rocky inlet below, shimmering pure turquoise. According to the map, this was one of several such formations on the lava trail: steep ascent followed by steep descent, each sequence ending in a bauble of surf and shore. Now that he was at the top he picked his way towards the bottom, the heat travelling right along with him. Half-way down he stopped and mopped his face, taking a long look at the crescent of rock-beach below. All the stones were white or off-white, all except one that was bigger than the rest, and greenish. He looked up at the lava cliffsides next, and saw some of those same beach stones, the whitest ones, arrayed in a spooky design, like a Halloween thing. It was a giant stick figure with the jitters, arms and legs flying every whichway. How they ever got the white stones to stick there against the sheer black walls baffled him, but there they were, bright against the dark rock and gravity-defying – a bunch of crazy bones in a dance for the sea.

Ray slugged more water and resumed his descent. He kept going until he was off the cinders of the path and onto the glinting beach, wondering whether his toes would fry if the sandals slipped off. He recalled a story he’d heard in the Arizona desert about vultures, how they vomit on their feet to cool themselves off. He got a good look at the large greenish stone and saw it was no stone at all.

It was something out of the pages of National Geographic, a honker of a sea turtle, green and horned and still as a boulder. And for a sea turtle it was quite some ways from the sea, well above the ragged edge of dried gunk that Ray reckoned was the high tide mark. The last time he had been so close to a turtle this size was in the Boston Aquarium, ages ago, when he pressed his face to the glass and stared at it floating his way, beak to beak. By Ray’s estimation these were rare creatures, ancient and endangered, and to him the lunker at his feet was either dead or dying in the sun, by now as hopeless as a roast in an oven. He gave it a wake-up shove with his foot, then a rap with the plastic water bottle. No response, not a flicker, and suddenly he had a new plan for the morning. He seriously wondered where his surge of resolve came from—maybe from the heat broiling his brain, soaking through all the sarcastic crud to strike some buried lobe that governed empathy and pity. He turned on his heels and took off with newfound zeal. He clambered up the side of the lava, re-entered the resort grounds and stormed into the lobby.

“What are you going to do about it?” he demanded of the desk girl, the same one he had locked horns with over the map. “Maybe the thing isn’t dead. But it sure can’t get back to the water by itself, not from where it’s stuck now.”

For a response, she gave him even colder treatment than the turtle had. The voice as flat as a scripted courtesy speech on loop. “That location is off property. I’ll report it to the maintenance people, but they aren’t allowed to interfere off resort grounds.”

Ray set his two rotund forearms on the thick black plank and pushed his face at her, bull-like. “That thing is probably a hundred and fifty years old,” he said, “and you’re going to let it just cook there?”

Finally she allowed him a burst of eye contact, but hardly the happy kind. “If the sea turtle is as old as you say, it didn’t get there by being stupid. It’s probably napping.”

Ray could hear his voice swelling, and he could see other heads start to turn. “I kicked it,” he said. “If you were napping and I kicked you what would you…”

She broke eye contact and lowered her head, so he was aiming his words at nothing but the jet black crown of her head. When her island face came up it was different, flashing something he had never seen from a concierge type. There was a warning in it, and a silence so venomous he considered backing off. But by then the big door had opened and the man with the look that said European-in-charge pushed himself into the fray.

He had one of those walrus mustaches reminiscent of Von Bismarck and a cracker suit to boot, linen white as coconut meat. He seemed twice as large as the girl he loomed over, as though he were capable of biting off half her head. Instead he crisply sent her to the office he had emerged from, his raised arm sharp as a Rolex hour-hand striking nine o’clock.

He addressed Ray in the manner of a general in the Swiss civilian army. “We are all servants here, including me. She should not have talked to you that way.”

“How could you hear how she talked to me? Your door was shut.”

The look he gave Ray said don’t ask and don’t think. And don’t try to do my job for me. It was a look so dictatorial Ray actually felt, of all things, a flutter of concern for the girl. In it was an unpleasant image called up from days gone by: the shod foot of the planter crunching the native’s neck.

“I hope she still has a job here,” he said. “People do have disagreements.”

But when all was said and done this was a polite lie, and Ray knew it. The truth was, having the girl fired was appealing—he couldn’t lie to himself—and, in the best of all possible worlds, maybe towel boy could get the gate right along with her.

But his comment about the girl’s job evoked no more than a cool managerial nod, neutral as Switzerland. “Nobody on their vacation should be fretting about the life and death of giant turtles. Why don’t you leave that to us, Mr. Ryan. And meanwhile…”

He reached into the white suit jacket, pulled out a gold pen and scribbled a note on stationery embossed with the sugar plant logo. He slid it into an envelope and pushed it across the black plank to Ray. “Drinks all day are with our compliments. Enjoy.”

Ray carried the envelope to lunch, where he devoured a shrimp salad, washed it down with two Long Island Teas, canceled a 3:18 tee time and marched back for another bout with the lava trail. Ray was too curious not to—the cynic in him said the beached turtle would be no better off than before and he figured the beast was likely fouling the air like any dead fish left out in the sun.

The high afternoon sun was on fire, and the dancing bone-stones looked even more bleached against the dark cliff-side. Down below the beach rocks were wall-to-wall as before but the turtle was missing. Ray searched up and down, scouring both the beach and the shallows of the surf, but nothing resembling a greenish hump remained. He felt a rush of self-importance. Based on the evidence, he had gotten Cane Palace off its ass—they had either pushed the turtle back in the ocean if it was alive, or carted it off if it was dead. At any rate, one thing was clear: he could resume his fat-melting regimen. Which he did, huffing in the sun as he soon reached the top of the next black and jagged rise.

He looked down to the new cove below, expecting to find another crescent of white beach rocks. Instead he saw green, green, green—humps everywhere—fifteen, twenty of them. Out of the water, burning in the sun. He double-timed it down the thin, spiky trail, nearly stumbling twice, furious at himself for making yahoo assumptions, for being such a tourist. Turtles! For all he knew they could fly or disappear into the earth, they could squirt on SPF50 every day and waddle onto the shore to sunbathe, just like any other Cane Palace guest.

Ray approached the closest behemoth and, just like before, was about to knock on its shell with his plastic water bottle. But a human voice interrupted him, female and spear-sharp, yelling something so primal it seemed beyond language. He turned and saw mid-way up the cliffs, the desk girl, descending fast, as if the lava offered her all kinds of footholds he hadn’t even noticed. Gone was the decorous khaki and green career apparel she wore in the lobby, gone was the polite arrangement of her long black hair. She had on one of those sequined surf tops and frayed jean shorts and everywhere, even in her flyaway hair, she flashed pieces of shiny stuff that could have been razor blades or bone shards. From her tone and the way she moved his way, Ray concluded two things: yes, she had been fired. And two, she had it out for him.

He took the measure of her—a girl, for Christ’s sake—and resolved to confront her with the best stuff he had, words from the heart, or at least from the heart he felt now in his throat. He was on the workers’ side always, all his life, no doubt about it; he came up working in the underbelly of old factories, peeling asbestos from the pipes. Never in his life would he try to get an island girl canned, and he had specifically asked the Swiss boss…

The words bubbled up, his apology and defense, and Ray lurched over the rocks and around the boulder-backs of the turtles to get within earshot. He shoved a hand in his shorts to check for the wad of bills—he would peel off half of them it that’s what it took, to show her that she mattered, that he gave a shit about her life and her future.

Then he saw from another part of the cliff what he hoped he wouldn’t but knew he would—two of the beach attendants, the Polynesian Tarzans with the towels and the jellyfish, scrambling down too. What they both looked like, the raging hair, the tattooed chests that seemed war-painted—to Ray they leaped straight out of the warrior art he had seen in the lobby. Both of them loping towards him, making that same unearthly whoop as the girl, made him change course and swivel into reverse, only he lost his footing and fell hard on the hot white stones.

The way Ray landed his face came up inches from the head of one of the turtles, so close to the side of its beak he could smell the salt on it. As he tried to get to his feet he saw a big wrinkled eyelid move, saw it open and shut just once. It was like the world’s oldest man winking at him, giving him the one-eyed chuckle, thinking about the wild old days when the beaches were red with blood.