As the sun rises, the rays brush Mickey’s neck and reveal a raw impression left by the belt. A premature scar, fighting for life. The skin has the texture of used chewing gum stretched to the point of tearing. Bronson hopes it will fade soon, so he can stop looking at it, so Mickey will stop stupidly asking, “What?”

They are on 95 again, rolling towards Baltimore. This time, families and friends are walking against the traffic, towards Washington, even though the die-in has ended. It’s somewhere to go, something to do, a reason of sorts. Bronson considers he and Mickey’s trip, the value in it, the nature of its hum. He can smell everything today. The baseballs at his feet rattle and vibrate with the car. The dried clay, the sweat, the rain collected in a few of them; he can smell it all. When Mickey reaches for a beer, Bronson doesn’t bother to stop him. He can smell the alcohol in his sweat.

Bronson grabs one of the balls, tosses it in his fingers. He sets his middle finger along the U of the seams, flicks his wrist, spins the ball. He was never a pitcher, never had the temperament for it. Leave a fat one over the plate for one batter, drill the next one in the hip to make up for it. As a catcher, he only really knew how to throw the ball from his ear, a western quick draw. The good pitchers were as flexible as gymnasts, the greats would spread their wings on the mound. Bronson was always plagued with a perpetual tightness. A rigidity he couldn’t shake.

When Bronson stops spinning the ball, he spots a faded signature, almost removed with the peeling skin. He grabs another, spins it until he finds a name on that one, too.

“Are all these signed?”

“Mhm.”

“By who?”

“Old friends. Old enemies.”

Bronson can’t read the name on the ball in his hands, so he tosses it in the back and sifts through the rest at his feet. Few ball players have signatures that make sense. He has an old ball signed by Cal Ripken Jr. back in Savannah, something he paid too much for on the internet. When it arrived in the mail, he thought he’d been ripped off. The signature looked like it read Carl J.

About the tenth ball he checks, the signature is pretty clear. Full name, including the nickname in quotes: Frank “Cosmo” Jones. Bronson reads it too many times, waits for it to evolve into something else. His waving depth perception churns his stomach. The curve where his neck meets his shoulders turns hot. There’s a tickle in his throat.

“Patient Zero,” Mickey says.

“Don’t say that.”

“What difference does it make?”

Bronson presses the ball to his forehead, rolls the seams against his skin, his skull. How must it have felt to sign a ball that rookie year? He signed plenty his short stint in the minors, but those are nothing. They are all in somebody’s practice bucket or have fallen down a sewer grate. Someone should open a landfill for all the baseballs in the country. Something on a floating barge. An island the size of Camden Yards. Let it cruise until it sinks. Let it join the ghosts of the Titanic, of Atlantis, of other things forgotten.

“How’d you get this?”

“Kid’s father was in the Show with me. Was our fifth outfielder. That spring training, they spent a lot of time at my place.”

“You knew him?”

“Mhm.”

“Mickey’s driving faster now, foot heavy on the pedal. Bodies line the shoulders, but the rest of the road is open. Nobody else in their lane. The seat presses into Bronson’s back and he adjusts his posture. The engine sounds like the swell of chatter, which doesn’t make any sense to him, and Bronson believes it must be all the voices they are passing.

“He had a little thing for Rachel, too. Kept grabbing my pictures, asking me if she’d wear his jersey. But yous were hitched then.”

Faster now. Mickey is hovering near 100. Something unfamiliar is flapping in the sky, featherless wings, a slick pointed tail. It’s too far away for Bronson to make it out, too just on the periphery of the windshield. It moves between clouds with a fluidity that suggests it’s unmechanical.

Rachel’s absence lingers softly today. Could be Mickey’s neck. Could be his growing neglect of sleep. Bronson feels resigned to whatever may come next. As the car speeds up, as the passersby become one stretch of blur, he feels capable of letting go.

A green marker says Baltimore is another thirty miles. Bowie is only exits away.

“Slow down.”

“Fuck off.”

“Take me to Bowie, Mick.”

Bowie was before Rachel, before he stopped playing. Maybe there’s solace in his old stomping grounds. Maybe there’s a perspective he’s yet to chew on and swallow. He could use some nourishment.

Mick releases the pedal and the car rolls off the exit. At the light, two men dressed as Mark McGuire and Sammy Sosa hold signs that say The bats are dead and They belong in the ground.

Prince George’s stadium is stained with vines and other vegetation. Splotches of green graze its exterior walls and blades of grass squeeze between sections of sidewalk, from underneath parking curbs. Life creeps and reaches and ignores the perpetual, shimmering ash of fading belief systems.

Mickey parks the car near the right field foul pole. What was once a golden beacon of authority now fades with the gray sky it occupies. The fence between the right field wall and the green lawn of general admission has been torn down. Further into the field, turned on its side, is an old Volkswagen Beetle. Something from the twentieth century, rusted and sunken in high reaching grass. The hood is smashed inward, the windows are broken open.

“Come here and carry this for me,” Mickey says. He’s filled a bucket with most of the baseballs from the car. He slings the wooden bat over his shoulder, slides a couple of mitts over the knob.

The grass is soaked in dew and it leaves damp stripes against the creases of Bronson’s jeans. The sun bears down on his neck, petting his exposed arms. It should be warmer than it is, but the sun’s burn can only do so much to a man with a blistered heart.

They reach where home plate should be and Mickey tosses Bronson a glove. “Got to warm up,” he says.

They stand only feet apart, tossing the ball without taking a step. Bronson’s shoulder moves fluidly, without a thought, but his elbow winces and resists. It’s been years, but throwing a ball is like riding a bike—except you were born to do it. With each throw, the tickle in his throat grows a little sharper. He holds in the cough as long as he can until he hacks something into the nearby clay. It settles like yolk in a cool pan.

Mickey takes a few steps back, begins going through the motions—lean back, step forward, carry the body all the way through—slings the ball with a little more snap. The squint of his eyes is pure baseball. The raw impression on his neck looks like a second mouth, the corners of its smile creeping closer to the crust of his ears with each pitch. With every toss, the less Bronson believes the night before.

“You ready?”

“Hm?”

“Grab the bat.”

Mickey saunters over to what’s left of the mound. He searches for the rubber, cleats himself a divot. He swings his arms in circles, spits on the grass.

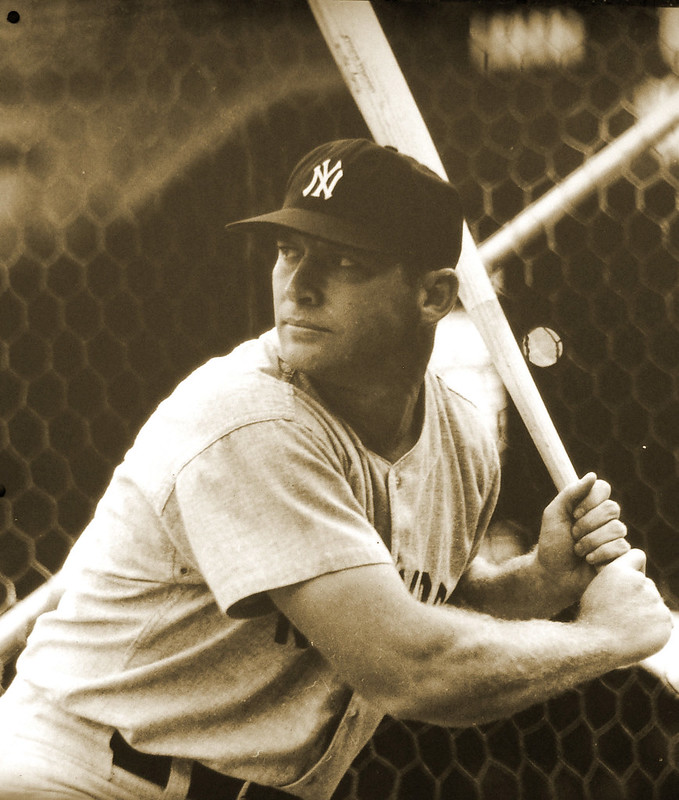

Bronson rests the bat on his left shoulder, twists his knuckles. He takes a couple cuts but knows everything is rust. Each fire of the hips induces premature soreness. Bronson looks to the outfield wall, wonders whether or not he could reach it, and considers refusing to bat.

“Mick.”

“Motherfucker, step to the plate.”

He steps in the left batter’s box, immediately uncomfortable with how level it all is. High grass, flat clay, empty seats. It’s all wrong. He reminds himself to keep his hands inside, to not let Mickey ride him off the plate.

“Hands off the shoulder, kid. There won’t be any walks today.” He pulls a beer from the pocket of his shorts, takes a big gulp then tosses it to the side. He kicks the clay in front of the rubber again, finds his footing, and gets set. He plays with the ball in his glove, twisting it before finding his grip, then delivers one from the hip with more whistle than Bronson expected. It sails past without a swing.

Mickey reaches into the bucket and grabs a new ball, delivers another. This time Bronson swings and misses everything. The bat slides and the knob beats into his bottom hand. He can feel his hunger in the movement. The momentum of the whiff sends Bronson twirling on his front heel, his eyes down the right field line. His dreams have returned. They’re pulling on his cheeks.

“Why you looking that way? Ball’s behind you.”

A few more cuts, a few more misses, and Bronson slings the bat against the backstop, pulls at this hair. The blisters have spread to his hands.

“I see why you quit.”

Growing up, hitting a baseball was the most natural thing. Load up, watch the ball get fat, and send it somewhere far, far away. Instinct, desire, feed. By the time Bronson got to Bowie, something changed. Each plate appearance became a battle with his own expectations, a newly developed anxiety. No amount of clay could absorb the sweat of his palms, and batting gloves only made it worse. The yips—a flu of its own kind. A disease with no known cure.

What was once second nature had turned into treading water—drowning beneath the Mendoza line. The further along into the season, the more frequently he was chasing garbage outside the zone. Above the letters. In the dirt. Half-hearted swings at pitches far outside. Once, with two strikes against him, Bronson swung at a slider that cut so far inside it struck him in the chest. He returned to the dugout having left two men on and a new bruise above the sternum.

Bronson picks up the bat, returns to the box. On the next pitch, he swings with a sense of urgency, just enough to send the ball down the left field line. The contact surprises both of them—the echo of the wood, the slice as the ball rips through the outfield grass. They watch it briefly, stunned he kept it between the lines, that he caught up to the pitch at all.

“Good,” Mickey says and grabs another ball.

This time the rotation is too tight to detect. The pitch dives into the dirt and Bronson swings anyway. His cough returns and something fills his mouth. Mickey throws one more, but when the bottom falls out. Bronson leaves it alone and spits phlegm on the mark in front of the plate.

Mickey proceeds to keep them in the zone, and after a few, Bronson rediscovers a rhythm. He’s no longer stiff in the box, he finds a real load in his swing. After sending one deep into the right-center gap, Bronson rocks back and forth at the plate. He sways with confidence. He shakes his shoulders loose. Mickey throws another, flat and down the middle, meant to blow right by, and Bronson sends it to centerfield, into the side of the Volkswagen. Another familiar pop.

His father-in-law buries his face in his glove, takes a few deep breaths.

“Low and in,” Bronson says. “I dare you.”

Mickey’s mustache perks up and he runs his hand through his hair, massages the grease between his fingers. He sends another slider but keeps it just off the ground. Bronson follows the break, drops the bat head below his knees, and sends the ball into right field, higher and higher, and over the wall. Bronson can feel his dreams attached, a dancing leash behind it. It disappears between some trees, slicing twigs, and scares a few birds away.

“Let me know when that one lands.”

Mickey kicks the bucket over. “Fuck.” He stomps the grass flat, marches a lap around the mound.

Before Bronson steps in the box again, he realizes he’s smiling. Eyes open, lungs full smiling. He balks at the passing happiness, and while there’s an itch to suppress it, to spit on it as he did the slider, he holds onto it. Then he returns to the plate.

When he looks to the mound, he sees Mickey struggling with the ball in his mitt. He rotates it, removes it, puts it back in the glove. Mickey can’t decide what to throw and Bronson feels himself sinking into the clay. He’s comfortable, ready for whatever Mickey sends his way.

If Rachel were here, she’d tell him not to get cocky. Stay focused. Ride the moment but don’t let it carry you away.

Mickey chooses a pitch and gets set. The trees behind lean a bit with the wind, blowing away from the field. Good. This next one will really carry. As Mickey delivers, the creature in the sky returns. It appears from behind the trees, flapping its wings, closer than before. Its tail is perfectly still behind it. Bronson hears a baby cry from the Volkswagen in center field.

Mickey delivers. Another pop. Bronson is on the ground. He doesn’t feel a thing.

His dreams are back, and he can see the creature in the sky is a stingray, graceful as it casts a shadow over all of Prince George’s Stadium. It swims into a cloud, taking a bite as it passes through. The crying continues, has a rhythm to it, and soon it fades into the trees.

“Get up,” Mickey says, but Bronson’s eyes are shut.