Dan and Ken were proud of the lives they had built in the South. They were brothers, both married, had designed their own homes, and worked for large corporations. Whenever their school was on television they threw a party. They and the men they invited would stand outside, get drunk, and deconstruct the game. Their wives and the wives the men brought would stay indoors, drinking, talking loudly and excitedly.

My wife Kitty would be among the women and I among the men. She worked with one of the brothers, I don’t remember which. I always got them mixed up, their names at least, though as men they were as different as a hot dog from a hamburger. One of them was older but had all his hair, and it was the younger one who had gone bald. One of them laughed like a horse, though I couldn’t tell you which, while the other kept quiet and lived in the shadow of his brother.

We had been to maybe four of their parties, but this was the last, something like the fifth. It could have been the thousandth. The boredom was instant and prolonged despite all efforts to eat or drink it away. Kitty told me that the women had also started to complain about the monotony, that maybe there should be a gap, parties once a month instead of every weekend. I’m sure we all felt very guilty about this because the brothers went all out: the food was plentiful, as was the beer, and bottles of hard liquor were arranged as if waiting for a glass. If a couple got terribly drunk the brothers always made sure they had a room or a whole wing of the house to sleep it off.

I couldn’t help it—I found the brothers’ affability cloying and repellent. Whenever they entered my space I moved as when a magnet forces another magnet to move. My bottle would suddenly become empty or my bladder full. I was ashamed to feel this way. I admit this to you now but never then confessed it to anyone, including Kitty. Because it was not just the two brothers I found tiresome but also most of the men. They giggled like girls or complained about trivial things, they took pleasure in the most puerile jokes, the most childish fashions. Grown men in cockeyed ballcaps. Worn indoors, even. One man whose name I cannot remember was an unabashed fan of not only children’s cartoons but also their pop music. I gave him the sort of berth that a ship would give to rocks.

The men were drunk and boisterous, as always. The wives were inside talking. Whenever the cooler looked as though it might be emptied Dan or Ken went inside and returned with more beer. Each time the door sucked open I could hear the wives talking loudly and excitedly. We all stood in the back garden. The game was over. The penury of my childhood has always been a sore that seemed to attract the salt. It was a subject that I avoided with great care. It was painful, profoundly upsetting, and so incongruous among such a group of people that when I introduced the subject it seemed not myself who began removing their coats with good cheer, laughing, joking, so genuinely excited I was not only forthcoming about the penury I had endured but also, without a hint of compunction, exaggerating. The men just looked at each other, mute with surprise and no doubt amused at my performance, wondering, I’m sure, if I was kidding them or not.

But they all agreed my idea would be great fun.

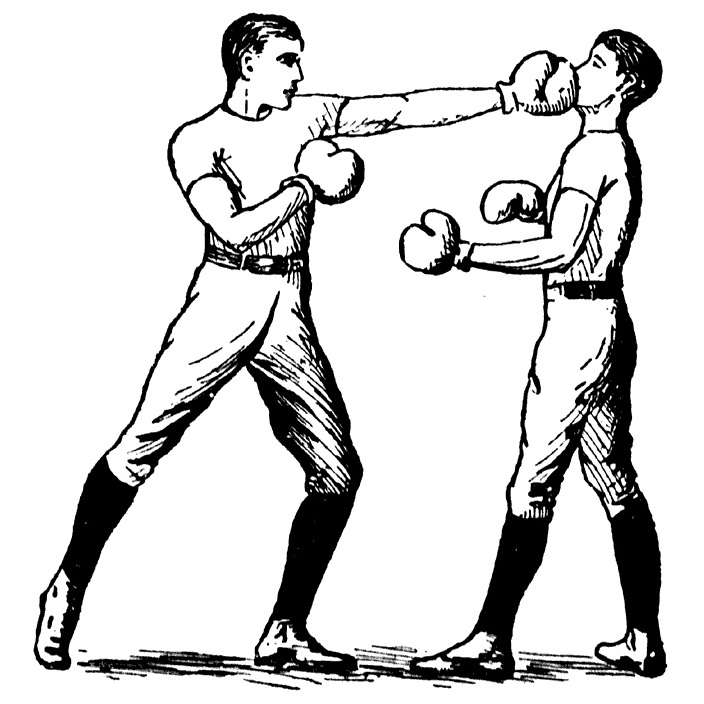

Dan and Ken both disappeared to gather the items I said would be needed. I placed a jacket down upon the grass. With the door left open I could hear their excitement carry onto the wives. I placed a second jacket down. The wives started to spill out onto the lawn. I placed down a third jacket. The lawn was humming with anticipation. Dan and Ken returned carrying handfuls of towels and plastic bags and shouting with the glee of schoolboys. I put down the fourth jacket and walked to the center of the square I had made and declared that I was now standing in the middle of a boxing ring.

Penury in many ways is similar to magic. It is amazing what one can conjure up out of nothing. I could not produce a rabbit from a tall hat, but as a youth I could, and often did, make boxing gloves out of towels and plastic bags. We all agreed that Ken and Dan should be the initial match seeing that they were the hosts. The brothers were also very keen to be the first to enter the ring. For a moment I thought they may have had some training, but their shadowboxing and swagger only betrayed a lack of understanding. I showed one of the brother’s wives how to wrap the towel around her husband’s hand. Next I showed her how to keep the towel in place using the plastic bags. I dressed the other brother myself then checked on the wife’s job. It was excellent. When I congratulated her we clinked bottle to glass.

To loud cheers the brothers entered the ring. Seeing that it was my idea I was to be the referee. I introduced the brothers using old appellations so filled with cliché nobody seemed to care. The brothers grandstanded and pantomimed in their corners as if playing to a great crowd. I couldn’t help but laugh at their antics. Someone had a thought and brought back a kitchen timer. I forgot to lay down the law before sounding the bell, and the brothers advanced from their corners.

For the first thirty seconds, although it seemed like half an hour, the brothers held a good deal of acumen, keeping their distance and not yet swinging wildly. But once the jokes turned sour they closed in. As it is with successful men, neither brother was concerned with defense, it was all attack, attack, attack.

Violence can be a funny thing. It makes some people laugh. Violence can be funnier than any joke. There was a time when the knock-knock joke was funny, but a man falling from a ladder can get a laugh that no joke could ever hope to inspire. Caught up in the moment, I neglected to tell you that what the brothers really had upon their hands were not boxing gloves but bricks.