“The beauty or ugliness of a character lay not only in its achievements, but in its aims and impulses; its true history lay, not among things done, but among things willed.”

-Thomas Hardy, Tess of the D’Urbervilles.

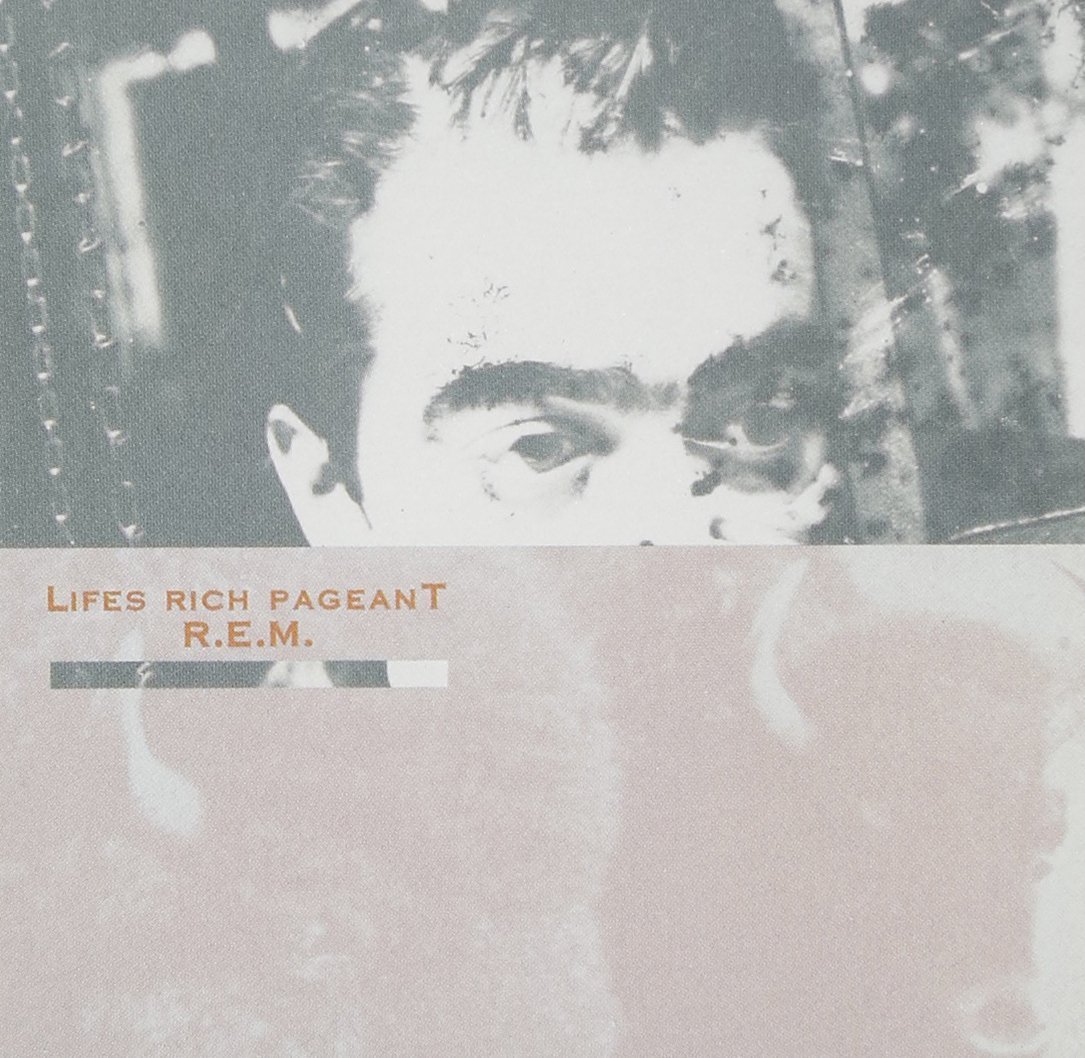

During my first semester in college at Northern Illinois University in 1987, everyone on my dorm floor—Chicagoans all, except me—owned a copy of R.E.M.’s Lifes Rich Pageant. I coveted this CD, wanted to know it, wanted to take it to my room and give it a private listen. There was something artistic, even weirdly classy, about its odd mixed-media cover, the band’s non sequitur name, but I couldn’t ask to borrow it. I didn’t want to admit I was all but clueless about the band, a fact my fragile eighteen-year-old psyche in this new environment couldn’t own up to. It was best to sit back, look cool, wait for my opportunity.

The opportunity came in the form of a CD rental store on the bottom floor of a strip mall along N.I.U.’s main drag. At the time, CDs were just becoming vogue, mostly because they were “forever choice.” That is, if you bought the CD version of an album, “You’ll never have to replace it again.” What if you threw the CD to the floor? Stomped on it? Broke it in two? Didn’t matter. That was how wonderful these things were. We believed it because we wanted to believe it.

Apparently, the resilience fable of CDs was enough to make some poor sap open a CD rental store at N.I.U., and I’m glad he did, because I finally had an un-embarrassing way to explore the band. The rentals were cheap too. A dollar a night. For that price, I dropped a five on the counter and got every R.E.M. album to date. I took them back to my dorm room and spent the night listening and, of course, recording cassette versions. For five bucks, I’d procured the band’s entire oeuvre.

I look back on many moments in my personal and, for lack of a better term, artistic development with a knowing smile. There was the day I quit my baseball team the summer before ninth grade, knowing I needed something new to round out my identity with high school approaching a few months later. There was the moment I opened my first bass guitar’s case, which lay in the grass as my mom sat in her car, the driver’s side door open so she could see, the engine running. I’d asked her to pick me up from my summer paint job at the Frus’, which was the perfect opportunity to show her the bass guitar I wanted to buy from the oldest Frus brother with the money I’d make from the job. (That $100 wouldn’t even make it out of their house.) I flicked the case open, and the afternoon sun hit the instrument squarely, making its sunburst finish pop like I’d never seen it before. “It’s beautiful,” Mom said, and that junky Hondo II indeed was. As the sun shone down on it, I knew what obsession would replace baseball. Rock bass became my primary focus for the next fifteen years.

Until R.E.M. came around, I was largely in the shadow of that sunburst, playing along in my bedroom to Rush and Led Zeppelin records, jamming in cover bands, never doubting the infallibility of bass heroes Geddy Lee and John Paul Jones. My loud and heavy ethos faltered a bit in late high school when I found U2’s Under a Blood Red Sky, but even that band didn’t fall too far from the hard rock tree. Bono was at least as much of a ham as Robert Plant, and The Edge was being hailed as a new kind of guitar virtuoso, featured in Guitar for the Practicing Musician alongside more obvious wunderkinds like Eddie Van Halen and Randy Rhoads. I took weekly lessons at the local music store throughout high school, learned every song anyone would teach me or I could figure out on my own. I was well on my way to becoming the bass player of the best heavy metal cover band rural Illinois had ever seen.

Then I brought those five R.E.M. CDs back to my dorm room.

The facets of my life that were realigned that night were multiple. The albums provided a starting point for changes both musical and aesthetic, but perhaps most importantly, they were the first I’d listened to that I both loved and could vaguely imagine myself being a part of.

Until then, my rock heroes were seemingly ten feet tall (Gene Simmons), flamboyant (David Lee Roth), or possessing virtuosic musical talent bordering on the magical (Eddie Van Halen). I fantasized I might one day be like them the same way a comic book reader might fantasize about one day having x-ray vision. Fun thought, but in the back of my mind I knew I wasn’t cut from the same cloth.

The guys in R.E.M. weren’t powerful, flamboyant, or virtuosic in any traditional rock way. They sported thrift store clothes and donned more traditional haircuts than their heavy metal brethren. The bass player wore glasses, which outside of Elvis Costello was unheard of for a rock musician. Perhaps the biggest difference, R.E.M. seemed to go out of their way not to be photographed, greatly contradicting the “look at me” element most other bands of their day cultivated. It was a little hard to tell by scoping their CDs who the band was, what they were about. I suspected they were shy, awkward, a little ashamed for wanting the attention that comes with being in a national band, but at the same time oddly stylish. Experiencing these albums wasn’t escapism for me. It was to imagine what, with a little effort and luck, my own life might be like.

Image aside, the music on these CDs most separated the band from my hard rock past. Their songs harkened back as much to American Top Forty as to anything on a Led Zeppelin album. I’d listened to American Top Forty religiously every Sunday as a kid but abandoned it during my too-cool metal years. R.E.M.’s albums suggested both radio pop and hard rock, and yet they were neither. The vocal melodies were simple like pop music, but good luck understanding any of the words. The music was by and large guitar driven, but more jangly than distorted. No one seemed interested in soloing, least of all the guitarist. All this mumble and jangle left lots of room for the bassist to create tasty backdrops, which often drew me in as much as anything. Most striking, when the singer sang, he didn’t sound like he was at the front of the stage in some coliseum. I pictured him in the corner of a recording studio, not facing anyone, microphone to his lips, like the position offered the only way he could get the words out. Somehow this made him, made everything, more appealing. Being out of my mom’s house for the first time, surrounded by more cosmopolitan people I couldn’t relate to, deeply unsure of myself, I bonded with these albums. They told me there was a world out there not just for me to revere but emulate.

R.E.M. was one of the biggest commercial surprises during the fall of 1987. While their new album Document featured the hit single “The One I Love” and eventually surpassed a million units sold, I was jealous of the folks who’d gotten to the band a train stop before with Lifes Rich Pageant. The first song on Pageant, “Begin the Begin,” had a propulsive drum beat combined with esoteric lyrics that hinted at the new beginning I’d hoped for by going to college. Lines like “Miles Standish proud” and “Let’s begin again / Like Martin Luther’s end” sent me scurrying to reference books. The album’s single “Fall on Me” was no less gorgeous for its obscurity, with lyrics that hinted at environmental concerns that were just beginning to gain traction with the college set. The first Earth Day would come three years after the album’s release. “I Believe” seemed an energetic if vague manifesto of the purpose of our generation. “Superman,” the last song on the album, a cover sung by bassist Mike Mills, seemed, through the bravado of a pipsqueak lover, to perfectly empower a generation not just lost but “concerned,” as the chorus claims in “These Days.” I was teenage male; of course I wanted to have sex and look cool in my clothes, but I also wanted some sense of how to move forward in a world I sensed was expanding unchecked, that didn’t acknowledge an end to anything. Pop rock culture at the time—hair metal bands, holdover seventies heroes, pop balladeers—was largely oblivious to anything but its own navel (or the navel of its sexy lover), but now I had my own Supermen, who looked an awful lot like ideally tailored ragamuffin versions of me. We had cassette tapes, Pell Grants, Camel Lights, the newly-thriving MTV. We could do anything.

I saw the band in concert that Halloween, enduring a trip home to the Quad Cities to catch them at Palmer Auditorium in Davenport, Iowa. My high school friend Nick and I sported our coolest trench coats and took our reserved-yet-not-together tickets to the show. The venue was sold out, so in order to stay a pair we had to go all the way up to one side of the bleachers, in the very back corner, as far away from the stage as anyone. The band played for well over two hours, touching on each record liberally. I couldn’t hear very well, but I recognized the songs I knew, and was dismayed to hear ones I didn’t. Most memorably, Michael Stipe started the show in a long coat, and as the night progressed, he took items off, at one point winding up in what appeared to be a skirt ensemble. By the encore, he wore nothing but a T-shirt and pants. It was like someone shedding skin until he wound up with nothing but his most essential self. If I took everything away from myself—all the pretense and insecurity and false notions—what would be left? Back in Dekalb, I listened to each R.E.M. album over and over, searching for an answer.

My journey with R.E.M. was threatened, after my first semester, by my abrupt departure from N.I.U. Among other things, I’d screwed up my financial aid, making the shift back to Moline and local community college a necessary evil. As desperately as I’d wanted to leave my hometown, the truth was I hated Dekalb almost as much. My sad, drunk, lonely semester at N.I.U. brought many embarrassments, but at least I’d found a rock band from Athens, Georgia that seemed to perfectly encapsulate what I wanted out of life. I could’ve left behind everything from those four months but those cassette tapes, and it would’ve been a boon.

While trying to unravel the mystery of those tunes I’d heard at the concert but didn’t recognize, I found Dead Letter Office, a collection of B-sides and cover songs I.R.S. had released in 1986 shortly after Pageant. These were tracks the band on some level had rejected during their first few years of recording: cover songs that didn’t merit inclusion, originals that weren’t good enough, or songs they simply “got tired of,” as Peter Buck wrote a couple of times in the liner notes.

Their choices of covers were revelatory. The band opted to include three Velvet Underground-written cuts on Office, not to mention the opening track “Crazy” by Athens heroes Pylon. These tracks revealed bands I barely knew, each validated with R.E.M.’s stamp of approval. I’d try on these acts like the dress shirts I found while combing Quad City thrift stores, each a little older and stranger than what you might find at the mall, but all the more interesting for that.

Besides acting as curator, Office was evidence of the band simply rocking out. Many of the tracks—“Burning Down,” “Windout,” and the Aerosmith cover “Toys in the Attic”—revealed more than any of their albums a group of guys getting together and turning up the amps. Gone were the “concerned” enviro-rockers of Pageant, replaced by something more akin to an American bar band. As someone who liked to drink beer and play loud, it was significant that R.E.M. on some level liked the same thing. At the end of Office, the band drunkenly banters about whether their previous attempt at the American standard “King of the Road” had been recorded or not. You have to turn the volume all the way up to hear the back-and-forth, but you can bet I did. Every almost discarded utterance could’ve been another clue to them, which could’ve been a clue to me.

Despite not wanting to go back, Moline provided the perfect-sized pond to experiment with this R.E.M.-tinted worldview. At Black Hawk Junior College, I quickly found I was a hot commodity as a bass player, and within weeks I was in Damion’s basement trying out for his band. Damion, a drummer famous around Moline for having been the first person in town to get a mohawk, approached me in the common area of Black Hawk Community College.

“What covers do you guys play?” I asked.

“We play all original music,” he said.

That was hard to believe. Damion seemed to lack a vital ingredient to write original music, but I couldn’t have said what it was. I accepted the invite. Maybe I’d talk them into some R.E.M. covers once I got there.

That Saturday I set up in one corner of Damion’s basement as Bobby warmed up on guitar. I knew Bobby as a high school Ozzy Osbourne fanatic, and the pointy headstock of his Jackson guitar screamed metal. Neither Damion nor Bobby struck me as ideal players to be in a band with, but I could hang for one practice. Once I was ready to go, Bobby said, “Here’s the first song.”

“What’s it called?”

“‘Sensimillia Bud.’” Bobby broke into a hesitant rhythm that sounded cool as it bounced off the walls. Damion started in on drums, a reggae beat.

My stomach curled. Reggae, reggae, reggae. I had no idea what to do. Suddenly I remembered a lick called “Reggae” from a Mel Bay book I’d been forced to go through during my lesson years. The lick seemed stupid, but it was the only idea I had. I figured out the key and played the line. It was like I was stealing something I didn’t want in the first place, but the notes blended seamlessly with the rest. We were writing music. I remember thinking, That’s all there is to it.

We ran through other Bobby songs that day—“Natas,” which is “Satan” spelled backwards; “The Big C,” which was Bobby-slang for cocaine; and “NYNot,” which was about nothing as far as I could tell—and I came up with a bass line for each. I didn’t want the jam to end. I agreed to join the band only on the promise that we never, ever play a cover song.

I’d like to think I would’ve eventually found my way to original music, but R.E.M. no doubt helped grease the path that got me into that basement with those guys. Songwriting became an obsession that would last a decade and was only usurped when writing took its place.

Each of those R.E.M. records was my favorite at some point during the two years I went to Black Hawk Junior College and planned my next escape, but the band’s second album Reckoning probably meant the most to me. Central to the album’s appeal are the contributions of bassist/backing vocalist Mike Mills, my counterpart in the band. Mills was bookish-looking for a rock musician—skinny frame, youthful face, Joyce Carol Oates glasses—but his parts were the highlights of the album. His main weapon was his voice—higher pitched than the rest, which is perfect for backing vocals—but Mills seemed resistant to singing anything resembling a traditional backing part. In fact, on Reckoning he’s most notable when singing not backing vocals but entirely different lead lines, ones that barely acknowledge Stipe’s main vocal but are also weirdly complementary. The two main singers—along with the less frequent vocal contributions of Berry—create beautiful, often nonverbal pastiches that are all the more powerful for their seeming lack of relation. The verses of the first song “Harborcoat” utilize something of a call-and-response technique, where Stipe starts to sing and Mills follows closely behind, but the lines are so different it’s almost like they’re not listening to one other. When Berry joins in on the chorus, the three voices explode into a chaos of singing. It’s hard to keep track of who’s doing what, and it doesn’t matter. The overall majesty of “Harborcoat” transcends any member’s specific contribution, but with Mills’s daring lines in the verse, it’s hard somehow not to see him as the instigator. He struck me as brave; this geeky-looking guy wasn’t afraid to take make himself known. You can bet I took note.

Mill’s second major weapon on Reckoning is his bass playing, which also seems reluctant to link up in any traditional way with the band. With Buck uninterested to the solo/fill role of the rock guitarist, Mills has ample room to fill space with his instrument, especially on the heartbreaking “South Central Rain,” where his puckish bass work offers the perfect answer to Stipe’s vocal lament. To someone like me, who to the point of discovering R.E.M. understood the bassist’s role as primarily a support position, Mills was the most audible guy on Reckoning, and he offered hope I might someday be heard amongst the crash and boom of the rock world.

Mills’s prominence on Reckoning reveals R.E.M.’s most revolutionary element: its egalitarianism. In the beginning, rock music was dominated by stars. Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison. It wasn’t until the Beatles came around that folks started acknowledging band members other than the lead singer. Ringo may not have mattered as much as Paul and John, but we all knew his name. Name one member of Elvis’s band.

The point that no member of a rock band was insignificant carried into the seventies with rock supergroups like Led Zeppelin, Rush, and Cream, who prospered with large contributions from everyone, including bass players and drummers. Still, the members of these bands were all rock stars in the traditional, larger-than-life sense. Jack Bruce, John Bonham, Neil Peart. R.E.M. was the next logical step in the transformation from rock as a platform for individuals to one for a unified band, and the group embraced this all-for-one philosophy with a seamless camaraderie. Each member was a contributing songwriter, and a good one. No one bludgeoned their way to the front of the sonic or visual landscape with over-the-top musicianship or theatrics. A famous story has the boys in the studio making their first album Murmur. While listening to playbacks of the songs, producer Mitch Easter was struck by how often the members asked him to turn their respective parts down. Rock musicians were famous for asking to have their parts turned up in the studio, to the point it had become a cliché of the genre. R.E.M. was a kind of band machine that brought nothing to their music other than pride in the overall product. This appealed to my sense of how a band ought to be—a collectivist ethos, people who defended each other, brothers.

This all-for-one aura was punctured, as I attended junior college in Moline and searched for my way in the world, when R.E.M. signed a five-album record deal with Warner Brothers.

Let’s put this fact into context. Amongst everything else, R.E.M. had been an independent darling for the better part of a decade, signed to the small-ish I.R.S. Records, and much of their appeal stemmed from this association. For their last two albums, Stipe and co. had been fond of dissing corporate America both in song and in the press. They were active for causes like Amnesty International and Greenpeace. It was hard to rectify the band’s decision to leave I.R.S. and go with some huge conglomerate, the same label as Van Halen! Wasn’t this exactly what they weren’t supposed to be? I felt like the kid who’d just lost my best friend to the popular crowd. I needed an explanation.

In fairness to the band, there was really nothing left for R.E.M. to conquer on an indie label, and on one level it seems strangely defeatist not to want them to go pro. Wasn’t replacing acts like Warrant, Winger, and Van Hagar on the charts a sign of pop music progress? Part of me couldn’t stand the idea of R.E.M. songs mixed in with the hits of the day. Another part wanted them to slay.

Amongst these questions I bought Green, the band’s first album on Warner Bros., the day it came out in the fall of 1998.

The pop elements of the record were undeniable. The first track “Pop Song 89” seemed to suggest the band was ready to appeal to a broader, less discerning audience, while also seeming to poke fun at said audience. The lyrics were clear and up front; Stipe by then had completely abandoned the mumbling. Most riveting to me were two ballads: “You Are The Everything,” with lyrics that allude to the anxiety of the budding eco-generation for a planet that might not hold out; and “Hairshirt,” which returns briefly to the inscrutable yet provocative Stipe lyrics over a mandolin-infused accompaniment. “Hairshirt”’s closing repeated line “It’s a beautiful life” gave hope to late teenagers still stuck in a bedroom of their Mom’s house, wanting the sentiment to be true.

Still, Green was easily my least favorite R.E.M. record to date. The uptempo songs didn’t compare well with past rockers, and the singles from the album couldn’t hold a candle to “Fall on Me” or “South Central Rain.” Perhaps most striking, Green was the first R.E.M. effort with songs I regularly skipped (“The Wrong Child,” “I Remember California”). It was clear the band wouldn’t mean the same to me as it had in the past.

Which seemed to be part of the plan. With Green, R.E.M. had an implicit message: “We’re a big band now. Go find someone else’s cassette to cuddle with at night.” At the time of Document’s release, you almost couldn’t read a profile of the band that didn’t mention the Replacements—a drunk, Midwestern R.E.M.—Hüsker Dü—a louder, more overtly damaged R.E.M.—and Ten Thousand Maniacs—R.E.M. with an eco-cute female lead singer. Through these articles I came to know a whole genre of contemporary music that appealed to the part of me that not only wanted to be an artist, but also wanted to get drunk onstage, unleash my fury through song, and be charmed by eco-cute female lead singers. R.E.M. wasn’t just my favorite band, they were the head of a musical movement, one that wouldn’t take final shape until Kurt Cobain’s screamed “Here we are now/Entertain us,” and an entire generation was validated in its anger, ennui, and confusion.

Still, none of these new acts spoke as directly to me as that little band from Athens, and I searched their past work for reconnection. Their third album Fables of the Reconstruction seemed to offer the best shot, as it was the only one I hadn’t worn out by then. Fables was notorious among R.E.M. fans for being the worst record of their original five. It was rumored the band itself didn’t like it. While recording it in Europe, Stipe commented that the album sounded like “two oranges being nailed together.” This bit of nonsense was enough of a judgment for many fans to declare it worthless, but I’d always loved Fables. The first single “Driver 8” remains one of the band’s greatest, and the second “Can’t Get There From Here” was the silliest track the band had ever recorded. Most notably for me, two songs deep on side two were particularly arresting. The first, “Kahoutek,” featured Stipe lyrics so elusive they were almost non-existent. The one line I could pick out was the repeated “You were gone like Kahoutek.” (Kahoutek, I learned, was a comet that passed briefly through the earth’s solar system in the 1960s.) Still, the beautiful, haunting pulse of the tune suggests a narrator missing something that had passed by briefly and left, like my failed escape from Moline. The second song, “Good Advices,” taunted me with its big questions, “What are you going to call for?/What do you have to say?” Yes, I wanted a creative life, but what kind? A writer? A musician? And by the way, what did I have to say? Wasn’t that part of the deal?

I don’t know why I was so intent on nailing myself down when the band on those early albums clearly wasn’t concerned with the same, as evinced by Stipe’s often incoherent lyrics, the oblique elements of their album art, and their unwillingness to offer up something as simple as a clear band photo. All this vagueness was strangely appealing. It meant mystery, which meant possibility. Maybe somewhere in those cracks and crevices lay reason to believe I’d someday have a life like theirs. If that wasn’t in the cards, I’m not sure I wanted to know.

Exploring crack and crevices was what this period in my hometown held for me. I was 19, and for the first time I felt like I had I fighting chance with the ladies. While I’d been at N.I.U., I was an obviously horny incoming freshmen from some podunk town, dorming with the more sophisticated folk from Chicago and striking out left and right. In the Quad Cities, I was the guy who’d been away for a while, played music in a band, wore a biker jacket. I moved into the basement of a rundown house and would go out on Friday nights looking for interested parties. There were plenty of drunken parties and random flings, and I behaved in ways I’m not proud of now. I realize my morals were as murky as R.E.M.’s when they signed with Warner Bros. In the end, they were a rock band like any other, and I was a male teenager.

How far we’d both come from the perfect innocence of that first album Murmur. Much of the album’s lyrics have the pureness of being unintelligible, and when they’re distinct, they’re nonsensical. As one mess of a couplet from the album’s first song “Radio Free Europe” goes (at least as far as I can tell): “Keep me out of country in the word / Disappointed into us observe.” It wasn’t that you couldn’t pull anything from them. Rock fans had been deciphering mumbly vagueness since at least “Louie, Louie.” Rather, Stipe had a penchant for carefully mispronouncing words, especially at the ends of lines, seeming to make doubly sure no one could make any sense of the songs. Considering the above couplet, the first line seems to want to be “Keep me out of country in the world;” the second, “Disappointment is to us observed.” Not exactly transparent, but both lines suggest an us-versus-them stance, maybe a kid lashing out at feeling ostracized by disappointed parents. It’s a common sentiment for rock music, but Stipe deliberately avoids this path by what seems a conscious bungling of the words. The idea is there, but not quite. The words are formed, but not entirely. The only defense for Stipe was to say, “That’s the way I wanted them,” as he did many times.

Fair enough. But how could it not be that Stipe, a young artist at the time, was simply unsure of what he wanted to say? R.E.M. were very prickly about any of the four members being viewed as leader, and as lead singer, Stipe did everything he could (short of not being brilliant) to avoid it. You could argue keeping his lyrics nonsensical was a weird kind of loyalty to the band’s egalitarian principles, making his voice just another instrument in the cacophony of melody. I’m reminded of a Jim Morrison quote from toward the end of his life, something to the effect of “I don’t believe a vocalist is necessary for a rock band. Another instrument could just as well take its place.” I feel strongly Morrison was wrong. The singer’s voice is essential to the kind of listener embrace most rock fans crave, and adding words and sentiments to that voice can help reel an audience in. Hiding behind a wall of obfuscation didn’t work long for Stipe, who by Lifes Rich Pageant learned to embrace his role as lyricist and communicator of message.

Ironically, R.E.M.’s debut Murmur is considered by most critics as one of the band’s best, and by me too. As unintelligible as the lyrics are, there’s a clarity to the production that—mind-bogglingly—the band never quite achieves again despite fourteen more studio albums over thirty years. The only thing I can conclude from this is that R.E.M. didn’t like the way Murmur sounded, or they didn’t like the process of getting such great sounds enough to go through it again. There’s something pristine about the tones on Murmur that suggests deliberateness. If it weren’t the band’s first album, you’d think it was a concept album from the middle of their career—like KISS’s Music from the Elder—something they tried on a lark and quickly abandoned when it didn’t come off rock enough. Peter Buck is famous for preferring to record quickly, even if it means, shall we say, less than pristine results. I can’t help but believe this led the band forever away from Murmur-like production, and to their detriment. Some of R.E.M.’s most memorable moments come on the album. “Pilgrimage” and “Laughing” make up one of rock music’s most gorgeous one-two combinations ever, and “Talk about the Passion” was such an obvious attention-getter (with the memorable refrain “Not everyone can carry the weight of the world”) the band brought it back to be the single of their first greatest hits album Eponymous. Rolling Stone named Murmur the album of the year for 1982, unheard of for a band’s debut album and even more unheard of for a band on an independent label.

Despite the accolades, R.E.M. seemingly wanted nothing to do with becoming a studio act like the Thompson Twins. In this way they were more like Van Halen than they ever would’ve admitted. Rock bands at the time were boys’ clubs—as any female rock artist of the era will attest—and your job was not to fuss, turn it up, get in the van.

Still, R.E.M. and Van Halen had at least one crucial difference. It seemed every time I read a profile or interview with R.E.M. in Rolling Stone or Musician, either the members or the writer mention something about books. I distinctly recall one reporter, while covering an R.E.M. photo shoot, writing that Peter Buck took a paperback novel out of his pocket and read it while the photographer reloaded his camera. The Kerouac inferences, the bass player’s Joyce Carol Oates glasses—R.E.M. were bookish.

I wasn’t much of a reader in high school. I’d read what was assigned for class—or most of it—along with the occasional music bio of Jimi Hendrix or Led Zeppelin. Great literary works seemed somehow beyond me. But here were these musicians I admired, and they read novels. I wanted to try them too. Also, if I expected to get through college, I was going to need to learn to read books, big books, important books, one after another.

Under R.E.M.’s influence I took an English class called “Introduction to Mode” which required the reading of eight novels. This frightened me. Could I even read eight novels in sixteen weeks? The first, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, was 500 pages! At the first class, I learned I would have to read fifty pages before our next meeting in two days.

I picked up Tess every spare moment of those forty-eight hours, trying to get the pages read on time. My mom almost had cardiac arrest when she saw me on the living room couch, television off, reading a book. I managed to get that first assignment read, but more than that, I enjoyed it. I was fascinated by what I would later learn was the naturalism of the book, the idea that Tess was doomed from the beginning, that no amount of effort on her part could have changed her tragic fate. There I was, a young musician and hearty consumer of pop culture working my way through this huge, important novel. Wasn’t I proof of the exact opposite?

I attended my final R.E.M. concert, while the band toured to support Green, in March of 1989 in Iowa City. I was in my last year of junior college. My band was going nowhere. I was teaching bass guitar, reading, and taking any literature class I could fit into my degree requirements. I still had no clear vision for my path. I knew I wanted to be creative, but how does that work? I didn’t know any writers or musicians. The four guys who’d occupy the stage that night were the closest thing to artist friends I had.

R.E.M.’s concert was at the dome on campus at the University of Iowa, where the basketball team played. The place held fifteen thousand people. It was where I’d seen U2 eighteen months before, and it looked sold out from my vantage a few rows up to the right. I attended the show by myself. I recognized people from my high school in the crowd, but I avoided them. I didn’t want to miss anything happening onstage.

The concert was less memorable than the one I’d seen a year and a half before. The stage was huge, the band far away, and a giant movie screen became a large part of the entertainment, showing abstracts during the songs and a funny “announcement” during a band break. The set was obviously scripted. Tracks from early albums were noticeably missing. They didn’t play anything from Murmur.

Still, Michael Stipe had taken even more strides to get outside that self-conscious singer from his past. He sported an eighties-style mohawk with a long braid down his back, and he danced spasmodically, seemingly inventing each step as he went along. One minute he was careening across the stage, the next shaking his shoulders, the next turning his back to the audience and singing to no one. I felt like he had to keep pushing himself to be entertaining, to force the issue. The painful, necessary process of becoming himself wouldn’t happen on its own; he had to will it. When the show ended and the last note of the last song was played, I drove home to Moline, knowing I’d have to do the same.

In a couple of months, my high school friend Randy called me from Phoenix. He’d moved there to live with his mom and get out of Moline. Randy talked of the mild Arizona winters, the great record stores in the suburb of Tempe, then asked if I wanted to move there as well. Phoenix was a major city in the west with over two million people; there had to be some kind of music scene there, along with a place to finish my degree. Randy assured me that Tempe had both. It was my one and only invitation to any kind of future like the one I’d hoped for. Phoenix would be it.

As I prepared to leave, it seemed appropriate to go back to the beginning and explore R.E.M.’s first EP Chronic Town, a five-song teaser that came out before Murmur and was the world’s introduction to the band in 1981. The original vinyl was impossible to find, but I.R.S. had included Chronic Town’s tracks at the end of Dead Letter Office. It’s almost shocking to see how far Stipe had come from the insecure singer of “Gardening at Night” to the commanding presence I’d just seen in Iowa City. Good luck making sense of any of the words on Chronic Town. Then listen to the bold declarations from Green’s “World Leader Pretend.” It’s not like Stipe had become David Lee Roth, but in the ensuing decade he’d become as much himself as anyone could’ve imagined for him.

I left for Phoenix in early January 1990, and R.E.M. would never hold the same sway over me as they did in the two and a half years I went to college in Illinois and yearned for a future uniquely my own. I needed the band on so many levels back then: their music, their imaginary friendship, their vision for a future that didn’t involve checking your essence at the door. I would want more R.E.M. as life went on, but I would never need them in quite the same way. And with their new millions of fans, they didn’t need me either. I can only hope some of those fans found something as essential to their souls.