1.

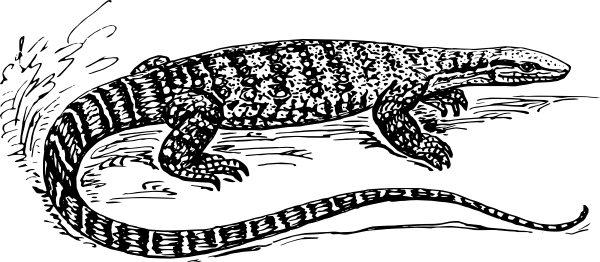

The lizard, an Egyptian uromastyx, appearing like a miniature dinosaur, crawled out from my girlfriend’s purse. I watched this creature lick the air, testing, before he climbed onto my thigh. I scooped him into my hand, brought his face close to mine. My girlfriend, laughing, twisting her head, turned the ignition. Two minutes earlier, Jacqui and I, each of us seventeen, our fingertips and lungs sticky with resin, stood before the wall of reptile tanks. This was our third pet store in as many days. Jacqui, still wearing her pompon uniform, a girl holding tight to her virginity, a girl whose breasts I’d kiss and massage for hours, bounced on the balls of her feet, nervous. I looked from tank to tank: turtle, corn snake, turtle, chameleon, iguana, then I saw him: an Egyptian uromastyx. This would be my second uromastyx. As I watched the uro scramble against the walls of his enclosure, using his thick, spiny tail for balance, I decided his name would be Prickle. He’d be named after the yellow dinosaur from Gumby, a television show watched as an unblemished youth. I turned and looked over my left shoulder. I saw that the store employee was busy with another customer, a sick rabbit. Quickly, I lifted the lid of the tank and secured Prickle. Then I tucked him inside Jacqui’s purse.

2.

My mother, father, and I gathered at the edge of our yard. The wind carried with it a sharp chill. I held a cardboard box that held the body of Lucky, my dead uromastyx. I was fourteen, didn’t know what to think. My father scratched his beard. My mother turned a plastic cactus over in her hands. I knelt and placed the box inside a small hole dug into the earth, covered the box with dirt. They said it was an infection of the lungs, the result of poor ventilation, particles in the air from improper substrate. We tried. We didn’t know. The year was 1995. Lucky came from Egypt, the land of pharaohs and Cleopatra. Now he was dead in a box in a hole in Midland, Michigan, U.S.A. No one thought to play “Taps.” My mother handed me the plastic cactus, a former feature of Lucky’s terrarium, and I worked it into the soil above his body. The three of us focused on the plastic grave marker. I stood and stuck my hands deep into my pockets. We turned and walked back to the house.

3.

At the start of the 1990’s, uromastyx lizards began to show up at pet stores across America. These early uromastyx were exported from Egypt and other North African countries, where they were called “dabb” lizards and eaten as a delicacy. Early owners in the U.S. were not prepared for the specific care requirements that these exotic lizards needed. Survival rates were low, and many uromastyx died within the first few years of captivity. Yet, the market persisted. The various species of uromastyx had potential to make excellent pets: being herbivores, uromastyx were docile by nature, welcoming to handle, and they exhibited playful personalities that escaped most other reptiles. Over the years that followed, experience brought with it a greater understanding.

4.

“Can we go visit Lucky?”

I’d shown the pictures to my son. The one with Lucky climbing the fireplace fence. The one with Lucky wearing a doll’s knit blazer. Now Seth wanted to see the grave marker, the plastic cactus. Seth was five. The year was 2008. We went to the edge of the yard and Seth spotted the cactus. Cracked and faded, the top broken off from years of relentless weather, the cactus still stood. My son was quiet. He got down low. I told him stories about Lucky, about the time we cuddled on an electric blanket, and Seth’s eyes went wide. Early on, even then, I saw in my son a future herpetologist, a kind-hearted boy who, when on walks or riding bikes, stopped to pick up stray trash. As each year passed, Seth continued his fascination with Lucky’s grave marker, the plastic cactus, a shifting symbol that defied my comprehension.

5.

I didn’t tell my son about what happed to Prickle. I didn’t tell him that I gave Prickle to a friend, that I gave Prickle to a friend because I was headed for court-ordered rehab. Mistakes were made. That much I knew.

6.

“Yeah, Spike. He’s a Spike.”

Christmas Eve, 2013. Dallas. My father drove our rental car, the FedEx ShipCenter receding in the rear window. Seth and I sat together in the backseat, a small white box between Seth’s legs. All of us vibrated with excitement. Carefully, I took the box and ran a blade along its taped seams. Texas provided more financial opportunities than Michigan. Seth’s mother moved them down south and left me to deflate like a punctured balloon. I opened the flaps of the box, removed a wadded bunch of paper. Seth lifted the plastic tub from the box, brought it before our eyes. Inside, moving as if in slow motion, an ornate uromastyx hatchling, no more than six inches from tip to tail, pushed his nose against the lid. We watched his lungs flex in and out. Seth named him Spike. I told my son that it was his job to take care of this little life, that his pet uromastyx now depended on him for survival. Seth smiled. He nodded. He knew and was ready.

7.

By 2014, the uromastyx was one of the most popular lizard species among hobbyists. The market had matured. With a much deeper understanding about housing and dietary needs, owners now reported uromastyx living into their twenties, projecting ages into the thirties. Despite the fact that export laws have stiffened, at times exportation banned outright, successful attempts at captive breeding have been reported. Accurate care knowledge combined with captive breeding has cemented a bright outlook for the uromastyx in America.

8.

I can look back and see myself trapped behind the glass of a squad car, can feel the cold-hard metal of the cuffs on my wrists, can hear the static pop from the officer’s radio. I remember the navy blue sheen of my lawyer’s suit, his reassuring tones. I can still access the shame, the guilt. Then I look forward and see my son kneeling on a South American beach. He’s digging through the soft sand. Now a grown man, Seth is carrying a baby sea turtle in his palm, its shell no bigger than a coin. I see my son’s hand at the shoreline, the turtle swimming free into the moonlit waters.

9.

“Hey, look,” Seth said, rummaging through the shelves. “We have to get Spike a cactus.”

Seth and I shopped at a Dallas pet store. We selected a climbing rock, a stone enclosure for sleeping, and at Seth’s insistence, a plastic cactus. A feeling of warmth bloomed deep within me. Back at Seth’s new home, as Spike scurried across the sandy expanse of his tank, we arranged the objects. We placed Spike’s basking rock, temp-gunned at a perfect 120 degrees. We placed the stone enclosure at the cooler side of the tank, the climbing rock in the middle. I watched as Seth worked the plastic cactus into the sand, guaranteeing a strong foundation. Seth knew to feed Spike bok choy, spring mix, and dandelion blooms, not spinach or kale. He knew about the calcium powder, the UVB bulb. My father entered the room, observed, and was impressed with our arrangement. The three of us watched as Spike climbed to the top of his rock. I questioned if he’d jump. Seth’s face was pressed tight to the glass. Spike jumped and landed, successfully, onto the roof of his stone enclosure. We all cheered.