Home

The wrestling room was in the rear corner of the school, a high-ceilinged rectangular box of cement block and white paint with a couple high windows so dirty they let in no light, and two large round halogens in wire cages that cast everything in a stark, whitish glow. There was no furniture in the wrestling room, just mats door to door except at the front, one rolled mat pushed to the wall that we used to sit on where we piled our bags and street shoes, and one small door in the back that led to a storage room cluttered with old gear and singlets and warm-ups. From the ceiling hung the climbing rope, which remained looped and pushed to one side. The rest of the room was dedicated purely to function: wall to wall, it was mat. The floor of a practice room is integral: at least two layers of mats must be laid, so that the cushion is adequate to soften the pounding on every part of the body.

Wrestling mats are expensive, and for good reason—the rolled layer is laid over wood or tile or concrete, and expected to bear the force of bodies raised to a height and accelerated to impact without the body below sustaining injury—though the head or chin, wrist or finger, might bear the brunt of first contact. The surface must be even, the tape that binds the seams between discrete sections pulled taught, and the puzzle of filling holes and gaps must be complete as possible, below and on top—dips and divots, gaps and crevices are the stuff of sprained ankles and torn ligaments. In college rooms, where the budget is adequate for practice mats cut and fitted to the space, the effect may be monochromatic and complete, school colors with logos wall to wall without a break. In our high school room, we bound scraps and pieces, especially for the lower layer: our necessary patchwork was an achievement of geometry and improvisation, triangles bound by their long sides to become almost rectangles, stretched and taped to meet other rectangles; gaps that we could not fill in the bottom layer stuffed with folded, taped towels to fill the holes. The top surface was also our competition mats for meets, though they were of two colors, one a deep purple and an ancient mat that had once been purple but had faded with the decades to a bruised, browned violet hue which has never existed before, and with luck will never be seen again.

I loved the old room, though it was dim and ugly and old, stank of the pungent antiseptic soap we used to mop the mats and the brininess of sweat that couldn’t really be scrubbed away. It smelled like what it was: a box of straining bodies on a soft floor, blocked in by padded walls, a training ground that contained as much of yourself as you were willing to release. In the outside world, everyone told you to hold yourself in—to talk right, walk right, do what you were told. In the wrestling room, you learned to keep a low stance or you would find your face in the mat; you learned that your body spoke better than your lips, that your body could only go where your heart willed it.

Transition

Each afternoon, I hurried down the halls of the school, a strange figure—I had ringlets of curls covering my head in a mushroom shape, and otherwise was a small boy with an exceptionally large backpack filled with perhaps twenty pounds of books and binders. I don’t know why Algebra II and Trig, World History and Biology had such heavy textbooks and nightly homework—or why I also carried not just the books for Literature, but also the two or three science fiction and fly-fishing books I was always reading at the same time, back then likely a combination of something like Elie Wiesel’s “Night,” Robert Heinlein’s “The Moon is A Harsh Mistress,” and John Gierach’s “Death, Taxes and Fly-Fishing,” all jammed in with a Trapper-Keeper and notebook filled with my notes, scribblings, drawings, short essays, a pair of clean shorts and two clean t-shirts. The bag was so heavy to cart through the quarter-mile long halls of South Eugene High School that I often gave myself bruises on my shoulders from the straps— there was no better feeling than reaching the wrestling room, and letting that weight go.

I’d take my shorts and first shirt down to the gym locker room, change quick, and jump right into the days workout set up by Coach Case. I hated weights, but I loved the burn, and the little bumps of bicep and tricep I’d gained since I started lifting. The short little gym room was cramped and overlit, smelled of bleach and sweat and iron, but I liked the sound of bars clicking and clanging, metal plates being slid onto bench press or squats, enjoyed the feel of the metal against the callouses I’d started to build after rubbing my hands raw for the first months. We did burnouts and max-sets, all of it too hard and in poor form, shouting encouragement and bellowing with effort, a cacophony of effort. All of it was done in twenty minutes, so that by three forty-five everyone was to be finished and lacing up their wrestling shoes back in the room.

Back in the room, I’d race to pull on my neoprene knee-pads and tighten my wrestling shoes, which have to be properly tightened and laced so that the loose strings don’t come undone or trip you up, and I’d grab my headgear from the backroom in the corner where I put it each day and join the guys already circling the room at a jog. The room would still be cool, the late afternoon light canting down from the high iron-silled windows in blocks of brightness that left behind great expanses of shadow, and as we jogged and tossed a ball back and forth, sometimes trying to pass and sometimes trying to bean someone who wasn’t paying attention, the room began to fill with a kinetic expectation, a loud gladness. The tennis ball would get to me, and I’d fake pegging Leon to make him jump and flip the ball high over my shoulder for young Truitt, who had acne and was painfully nerdy and too often hassled by the older guys on the team, and he’d gratefully catch the lob, toss the ball across the room in an arc, maybe catch somebody in the back of the head so that the room would echo with laughter. And we’d keep on like that, skipping and then circling in a stance, turning backward and forward, rolling or cartwheeling, keeping the ball moving until Coach stepped in to retire it, and it was time to circle and stretch.

Ritual

In the circle, the captains led stretches, sometimes from the middle, sometimes from the periphery—it was me for so long that I can’t recall what it was like not to call the motions, toe-touches and splits, back-bends and quad-pulls, the partnered series of elbow-crosses and pulls to loosen shoulders and joints, neck-bridges to build strength. There was such rhythm to it, and in the banter and familiarity, such belonging. Cartwright, who had digestive trouble, would let out a tremendous fart and sigh of relief as the five guys nearest hollered and scampered to avoid proximity. Leon and Woody would be going at it as usual, trying to out-brag each other regarding the number of girls in the sophomore class who’d given it up to them or wanted to or would. It’s funny now to realize just how few of the girls in the sophomore class probably gave either of them the time of day—they seemed confident in their braggadocio, so I believed them, as the number of girls in my life I’d dated or kissed remained a steady zero. Or, if assistant Coach Kessler’s wife, who was young and tan and pretty, had happened by, as she often did since she worked near the school, Lobue would start in again about how the assets she was packing weren’t lacking, noting that she had DEFINITELY married down, and probably wanted a young stud like him instead of a balding fat dude, escalating until, as he always had to, Kessler began to chase him with a rolled towel.

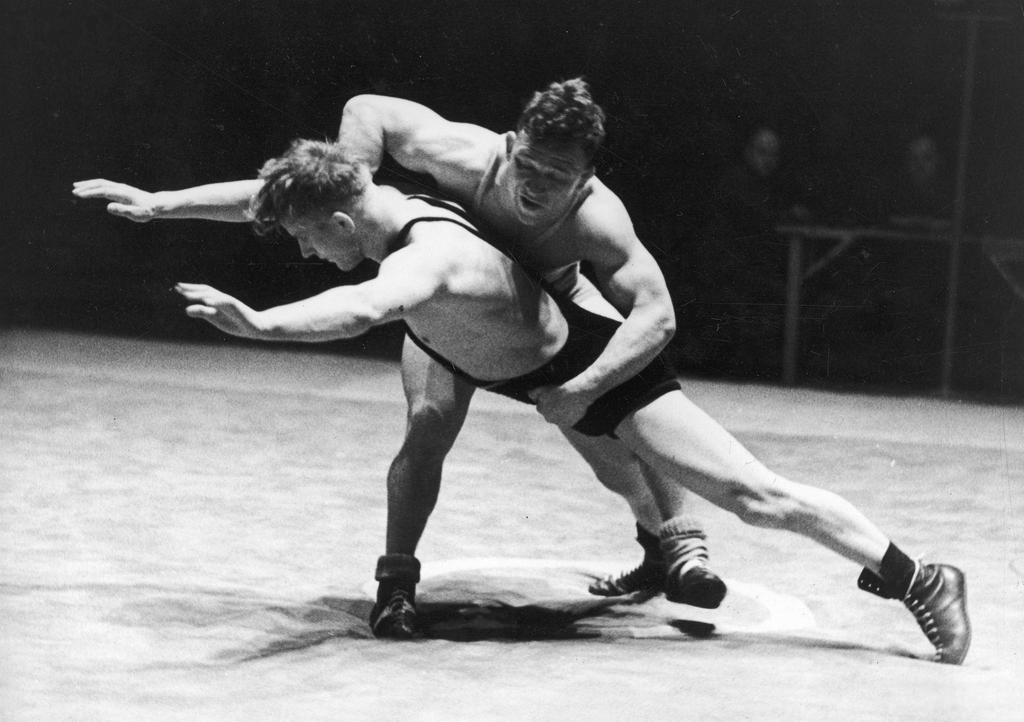

Soon enough we paired up and started drilling, which had its own logic and rhythm– pairs of bodies remain in perpetual interlocked motion, whether competing or drilling; the only difference between the two activities, to the untrained eye, is that if competing both bodies flurry in arced blurs, while drilling involves only one body, the other only reacting, being taken down or thrown, only to rise and assume agency. For a sport conceived of as battle, there is little bump and crash, and much reciprocity of effort and action– all is a mirroring or mixing, enacted by each pair in tandem simultaneously. There should not be space in a small padded room for such sustained drive and plunge, the suddenness and inversion and fall and rise and fall of so many bodies seeking individual dominion—the miracle of a wrestling practice is that all are thrown aloft and brought down, rising and falling and rising again, and most days none collide, nobody gets hurt. It is an improbable dance of angles and agency, abruptness and power, repetition and elevation and descent.

Grace

Sweat, blood and sinew—these are the offerings any athlete makes, and the violence of combat sport only exacerbates the aggregation of injury, the necessary pain and its final toll. Taped ankles, taped thumbs, taped knees swathed in pads to allay the tenderness of impact; headgear pulled tight to ears in attempt to prevent cauliflower, the loss of hearing nothing against the sense of enclosure, the feeling of being bound or jarred. The bone bruises, blue and yellow, blackened eyes and tie-dyed patches of grip and smack; the severed tendons, ACL and MCL, stitched or replaced with cadaver Achilles, that the knee is indeed an Achilles heel; dislocated fingers, sprained thumbs bearing perpetual tape; crushed ears, the blood and pus drained by needles; the perpetually sprained ankles, strained so loose that even after years of physical therapy and rehab, I can take a step onto grass or off a curb and find myself falling face-first at the slightest unevenness; the compacted and recompacted vertebrae of the spine perpetually misaligned, so that today I do not sit if I can stand, hovering perpetually in unrest.

And then, the concussions. The year I was knocked out at Junior Nationals in Fargo by an intentional knee on my backward rotation—out forty-five minutes, uncertain who I was or where I was when I came to, and had my father not been there, I might have tried to wrestle. That concussion nothing against the price of the move I was knocked out doing—my only great offensive move in Freestyle and Greco was the ‘Fin Spin’ or flying mare, the fearless backward arc of head to mat with the opponent swung after, and every time I threw a man my head would strike the mat, the better the throw, the harder the contact, and I threw well—it was my best move. I thought it was natural that every time I threw, a blinking constellation of flashing lights passed through my vision—which is to say, I knew I was seeing stars, but as I suffered no disorientation I couldn’t overcome, I thought nothing of it. We weren’t worried about micro-concussions those days, hadn’t examined the studies about headers in soccer. And I don’t know if I would have stopped with that beautiful armspin if I had known—it was the first and only move I ever really mastered.

I learned it at a camp put on by former Oregon Coach Ron Finley, ‘Fin’ to his friends– the grand old man of Oregon wrestling, who unfortunately lived to see them kill his program. Even in ‘93, he’d already put on the padding that old wrestlers always do—goodbye scale, hello bacon—but he always wore it well, still had the squat, powerful frame of a Greco-Roman wrestler good enough for fourth at the Olympics. Here was an older man with elven, cauliflowered ears and a rounded belly, legs protruding white and spindly beneath sagging sweat shorts– uncompelling compared to the lean, muscled counselors who’d been instructing us. His voice was oddly high and gentle, and he struck my teenage self as too kind, too enthusiastic as he addressed us. “You get your opponent moving, make him push just a little,” he said, demonstrating on Oregon’s 184-pounder, who towered over him by half a head. “When he does—“ there was a pause, a push and pull, and suddenly Fin was gone, bending back toward the mat in a clean bow spelled from head to heel, his partner following in a longer parallel arc, heels over head, before slamming to the mat before us. In that moment, wrestling had me hooked: I wanted to throw like that, to be ordinary one moment, and suddenly something more. And so I practiced that move a thousand thousand times in high school, could hit it so clean that nobody could stop it.

There is the quandary, then: the hundreds of constellations of stars flowering and blinking in the repeated strike of head to mat, the repeated flash of lost brain cells, the damage still unknown, and all the surgeries and lost cartiledge, the permanent disfigurement of the joints of ankle and thumb, the limitation of always being forced to stand, the constant pains, all preventable just by eschewing that beautiful arc, leaving the mat behind—and how I would do it all again, just to throw or be thrown, for the moment when the spin is irreversible and the impact imminent and total.

Obsession

It all began with good intentions, as most afflictions do—I was only a couple of pounds over the weight I needed to make, and my father, a doctor, suggested I cut my calorie intake just a little so that I didn’t have to dehydrate myself. He bought me a book which became my bible, the Universal Calorie Counter, which listed alphabetically, in portion size and preparation, the number of calories in every food. I read the book all the way through, consulted it before consuming anything to figure out how many calories I was taking in. Soon enough I didn’t need to look up anything, as the numbers were burned into my brain, and with them a new value system: foods which were high volume or filling and contained few calories were ‘good’, as they would leave me with the illusion of a full belly while sustaining the project of weight loss; foods which were high-calorie, especially foods high in fat or sugar, were ‘bad’, as they were gone in only a couple guilty bites, leaving me to feel the hollow of my stomach.

At first, I carried a small notepad as tally-book, recording every morsel as a guilty record—that is, I wished for clean pages, for a full stomach and release from the scale, which meant that I returned to the scale daily to verify whether or not I was actually getting lighter. This tally book was little more than a string of numbers—at first I recorded the foods and then the record of their cost in calories still available to consume: slice of bread, plain, 150 calories; large apple, 100 calories; lite yogurt, aspartame sweetened, 110 calories; cup of cereal, dry, 120 calories. Soon enough, I wrote only numbers, 50, 100, 250, 50, 25—as I assembled each meal so carefully that I didn’t need to name the foods. I ate everything slow, breaking bars into small bites so that they would last, a small pile of Power Bar crumbles assembled in a heap atop the wrapper before I ate them piece by piece. I sliced apples and pears into twenty and thirty slivers, crunching each between my teeth. I ate bread as a ritual, pulling the crust from each slice and then breaking the soft center into pieces unless I’d toasted it, in which case I separated the two halves to extend the pleasure, often scooping up bites of salad in the middle to make little pockets.

I reasoned that to really be able to lose weight, I needed to work out more so that I could eat more. A two hour wrestling practice, which burns two to three thousand calories (nearly a marathon) was not enough—each night after I finished practice I would run with my father another five miles after practice. We left from our house, passed under the freeway overpass and paralleled I-5 for a time until we came down to the river in the dark, its rain-swollen whoosh rising as the noise of traffic receded, my legs dead beneath me but still somehow floating me over the rain-black pavement as I matched my father’s steady pace, a ghost in the night. I ran until I was no longer hungry, no longer a boy running beside his father through the dark by a river which carved a valley, no longer there at all but for the slap of my feet to pavement. Back home under the hot shower, I counted the number of calories I’d earned, the reward of hot food that was imminent—the anticipation far better than the ruinous meal itself, which meant I had nothing left to look forward to.

The first time it got bad, my sophomore year, Coach Scott took me aside and told me I was getting too small for the weight, that I didn’t look good; I was down to perhaps 95 pounds, five pounds too small for the weightclass.

My cheeks were hollowed, pinching the edges of my mouth; my skin felt thin, every muscle pressing tight. I liked this death’s head leanness, all cheekbones and jawline. I had a six-pack even at rest, the blue veins of my abdomen pulsing below jutting hip bones so that if I pressed, I could feel the throb of my own blood.

“You listen to me,” John Scott said. He reached out his meathook hand and seized me by the forearm, found his fingers could almost touch. He stared down at his finger encircling my arm as if seeing me for the first time—perhaps he’d noticed I’d grown thin, but hadn’t really looked at how bad it had gotten. My arm grew hot under his touch, as if I could feel my own sick will pulsing there, trying to flee from reckoning. But Coach Scott’s grip was firm, and he wouldn’t let go. “You need to eat,” he said in a voice which suggested he was shaken at what I’d done.

My eyes raked the storage shelves over his shoulder, the floor, trying to find purchase anywhere but in his face. “I’m fine.”

He drew me so close I was smothered, forced me to meet his gaze. “You’re not fine, and you know it. You eat, or you won’t be strong anymore. You’ll betray everything you’re trying to become. You eat, and you get strong again.”

Humility

What I remember best now aren’t the warm-up jogs or stretches, the technique sessions or the drills, the long live goes or the nightmarish final sprints. I don’t linger on John Scott’s inspirational speeches and pithy asides concerning the ancient days of Greco-roman warriors. All I remember are the weight-lines, winner stays. Live wrestling on the feet with the whole team standing there, starting from the light-weights and then moving up and back down and up again. This exercise was impractical for training—most everyone stands and watches for most of the time, as only two people are competing at any given time. I hated it precisely for the reason John Scott made it a weekly practice my junior and senior years: it was made to humble me, a light-weight so relatively elite that my teammates could not usually challenge me.

We’d begin at the bottom; there were only the hundred-pounders lighter than me, one varsity and one JV, and then I’d take the winner down in a few moments and they would return to the line, leaving the other eighteen or twenty wrestlers to face me. And so it began—each man up had a greater and greater size advantage, and entered fresh, while I grew more exhausted with each ensuing go. The middle-weights soon caught on, each of them leaping on me the moment I’d taken down the previous man, powering forward with energy I couldn’t afford to match, or trying to force me to tie up with them so that their size and strength advantage could shine through. None of them had ever taken me down—and I was damned if I was going to let them. I shucked them, using their forward motion against them; dragged arms and snapped heads and passed elbows to avoid letting them get a grip. When I had to, I closed down to a tight stance and circled and danced, waited to recover my wind enough to take them on, John Scott bellowing from the side: “Get on him! He’s stalling!”

The first time through I managed to make it all the way to the end of the line, arm-dragging our younger heavyweight and slipping behind him—and assumed that I had won, having taken down everyone on the team, including several solid wrestlers who had forty and fifty pounds on me. That was when John Scott pushed the 185 pounder back in, indicating that I had to go back down the line. I was so astonished that I let the 185 pounder snatch a single and take me down, and just like that, the exercise was over. I stared down John Scott, and he grinned and said, “Why’d you stop?”

“That’s not—fair!” I said. “I won. You cheated.”

He shook his head. “Nobody cheated. You just thought it was over.”

The next week, he called the weight-line and started it all up again—on up the line with everybody’s best, until I was gasping as I managed to down the heavyweight, and then back down. This time I was ready for it to continue—but I couldn’t defeat the fatigue. I made it back to our 154 pounder, who was solid and came after me hard—though normally I could have avoided his simple double-leg, I was straining to breath, felt as if I was moving through mud, and ended up overpowered. And that was what awaited me weekly— the whole team arrayed against my will and conditioning. I despised it, for it had been my practice to never let anyone take me down in the South Wrestling room—there, I had been a self-styled King. Every week, I loathed the line; the few weeks we had competition or other commitments, I rejoiced. It seemed to me that it was unfair—that John felt he had to break me down by singling me out. For two years I faced the line each week, and never once was I glad to lose.

Now, when I think of the wrestling room, all I see is that line. What a gift, to have every boy on that team give their time to make me better.

I still hate the line, but not for the burning lungs and leaden legs, the shame of the inevitable humbling. I hate the line because now I know the world is a line, stretching on and on—and I will never get better at losing.