August 30, 2021, dawned unusually crisp and clear on Fort Benning, in south Georgia. The haze from the previous week’s artillery range fires had cleared, and an almost-forgotten coolness signaled the earth’s first tentative turn toward fall. The U.S. stood poised to exit Afghanistan, and the Taliban stood poised to fill the void. News coverage documented the chaos as the Taliban swept across the country, retaking ground paid for in American blood over the past two decades. Panicked Afghan civilians rushed departing flights, some clinging to wheelwells until they fell to their deaths. Four days earlier, a suicide bomber at the Kabul Airport had killed 13 U.S. service members and countless Afghans, as if adding final injury to insult. Little work got done at the Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence, where I taught communication as an Army civilian, those last two weeks of August. We tracked the withdrawal in real time via our chosen news source, individually, on our phones or computers in our offices.

I entered the building’s east wing early that morning and greeted the usual crowd of boys in the hall. We were nodding acquaintances, the way people are when they only catch little snippets of each other in passing. By that point, I’d seen these boys every day for over two years, so I felt like I knew them, albeit in a limited way. I missed them if I took a different way in and didn’t see them, anyway.

They presented a study in contrasts. Mark was popular in school, homecoming court, Mr. All-American, back in the day. Jeff had always been a practical joker. Sometimes I expected him to swap out the plaques on the walls while we were gone, just to see if anybody noticed. Brian was the thoughtful, careful guy, the consummate planner.

Some of them smiled, some challenged you with a direct gaze. People couldn’t help but be drawn to Doug. He pulled you in from thirty feet away—looked like he wanted to bed every woman that came within range of that dimpled grin.

They hailed from Springfield, Charleston, Pueblo, Elizabethtown. Great guys, all of them. The buzz this morning—that is, if they still had time to talk—would have been the Afghan withdrawal.

Captain Ortiz gimped in on crutches, bulging arm muscles propelling him forward in long, impatient sweeps. A dark-haired, smiling infantry officer, he exuded charisma. He lagged a couple minutes behind his classmates, who had already bantered their way into their respective classrooms.

“Hey, Captain,” I greeted him, “Let me guess, ultimate football.” It wasn’t so much a question as a statement. The officer students ran off energy on the football field on Wednesdays, beating each other into submission until somebody claimed athletic superiority. Invariably, two or three of them limped to class on Thursday with a new injury.

Ortiz grunted and shifted his weight, “High ankle sprain.” He raised a crutch to point to the plaque I had turned away from to speak. “It’s bad luck to read those things, you know.”

Now that he mentioned it, I never saw the active-duty officers reading the memorials for the war dead. They avoided them in the same way they gave Ortiz a temporarily wide berth, like he was the unwelcome harbinger of their mortality.

“I appreciate the warning, but I think the statute of limitations has run out for me.”

He shrugged as if to say, “Suit yourself” and clanged a crutch against the door of his classroom as he entered.

I turned back to Jeff Toczylowski’s plaque. “How you doin’ with all this, Toz?” I asked aloud. He didn’t answer, of course. These guys were my contemporaries. We didn’t, but we may well have stood shoulder to shoulder in the common spaces of our ROTC programs back on 9/11 and watched the events unfold in real time.

That morning, 9/11, felt a lot like this one. I jostled along with several classmates toward my Naval Science class on the campus at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, the flagship university for that Navy town, located not four miles as the crow flies from the world’s largest naval base. Norfolk is situated largely below sea level, kind of an east coast New Orleans. Its summer mornings dripped with heat and humidity, and we began many of them with 5:45 a.m. physical training. Our spirits were high this morning, knowing the morning’s cooler weather meant we’d finally turned the corner to leave the final soggy mid-Atlantic summer behind us. The sun blazed against a cloudless blue, the edges of everything crisp as the creases in our uniforms.

We, the fleet returnees, the prior enlisted, swaggered as we walked to the Navy ROTC building, stopping by the smoke pit to “burn one,” and give each other shit, as we did every Tuesday, the day we wore our uniforms on campus for drill.

Jason Redman, a SEAL Officer Candidate from Fox Company, passed us headed the other way at a trot:

“Hey, did ya hear?” He huffed without slowing. He flipped around and jogged backward. “Some dumbass hit the World Trade Center in a plane.”

“What?” I shook my head in disbelief. “What an idiot.” These were the days before smartphones in every pocket. Television and radio were the only games in town for details, and the smoke pit had neither.

What we knew from our enlisted experience was that the smoke pit often did hold the keys to the information universe. If you ever wanted to know the truth about what was going on, the smoke pit was the place to go. We speculated as we huddled around the butt kit before our 1000 class.

“How the fuck you gonna hit a skyscraper?” Jeen flicked his Bic and lit up. He was a former submariner, stocky and bald as a cue ball, slated to head back to the undersea service when he graduated.

“Man, somebody’s getting fired,” Jeff said, leaning toward him for a light. The flicker reflected in his slightly out of regulation mirrored sunglasses. Tall, lean and sandy-haired, Jeff had his eyes on an aviation future.

We all nodded and chuckled, smug in our assessment that the pilot screwed up. Tragic, but not much different than a navigational error that ran a ship aground. It was unfortunate, certainly, as lives were undoubtedly lost. But heads would roll, and we’d move on. It didn’t occur to us that the drive-by from Jason Redman meant our country was at war.

By 1030, nobody was laughing. One of our instructors, Lieutenant Swick, barged into the room and blurted, “We’re under attack,” and that was the end of class.

We crammed into the wardroom, the building social space that housed a 27-inch television perched atop a cabinet, and stood watching the news coverage. For once, nobody cracked jokes; almost no one talked.

We were set to graduate in May, back to a fleet that was certain to be at war. Most of the smoke pit crew enlisted on the heels of the first Gulf War and spent the first years of our careers riding the high of the 100-hour fall of Saddam Hussein’s Kuwaiti house of cards in 1991. In January, 1991, the big screen in my south Alabama college’s dining hall broadcast saturation coverage as CNN’s Bernard Shaw and Peter Arnett narrated the play-by-play from a hotel in Baghdad. I cheered as a U.S.-led Coalition of forces first crippled Iraq’s air systems, then routed Saddam’s elite Republican Guard. I dropped out of school on a surge of patriotism and joined the Navy shortly after my 18th birthday.

In the ROTC wardroom, a newfound consciousness of just how high the ante was settled in my mouth, acrid and metallic. We drew strength from sheer proximity, and a mix of bravado and helplessness permeated the room. Norfolk’s NBC affiliate replayed the footage of the south tower collapse, and Steve banged a fist on the table. “Fuck these fuckers, man. Bunch of cowards!”

Frank asked LT Swick if we could volunteer to graduate early and go back to the fleet. He answered with a knowing smile, “Don’t worry, the war will be there when you get back.” We could never have predicted just how right he was. The Global War on Terror soon stalked our officer careers, a desert-colored specter of war on two fronts, our generation’s Vietnam, the impenetrable jungle replaced by an unblinking sun on sand and rugged switchbacks.

Now almost twenty years later, I entered the east wing of the Maneuver Center of Excellence as a Department of the Army civilian, marveling for the thousandth time at my survival. Of the group that stood shoulder to shoulder on September 11, two would never stand again. Another had lost a limb, and none escaped completely unscathed. Jason Redman, the Officer Candidate who told us about the attacks, survived several gunshot wounds while leading a special operations mission in Iraq in 2007, and a grueling recovery afterward.

I graduated on time in May, 2002, and served most of the early days of the wars on ships, brief moments of terror punctuating long stretches of boredom. We chased pirates off the coast of Djibouti, trying to prevent ransoms from funding more al-Qaeda operations. We patrolled the oil fields of the northern Persian Gulf, seeking to head off supply disruption. We dropped Marines in Kuwait to roll up the desert roads to Baghdad in 2003, worrying all the while about Scud missiles armed with chemical warheads. We protected American citizens caught in the crossfire between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon and transported them to safety in Cyprus. It all counted, right? The years spent under constant threat of being sucked into the ground war as an individual augmentee to an Army unit, immediately after five years of sea duty? It did, and it didn’t.

My coworkers at Fort Benning, Army veterans, sometimes talked around the edges of their service in terms of body bags and traumatic brain injuries. I knew I was one of the lucky ones and kept my mouth shut. As an Army civilian teaching active-duty infantry and armor (maneuver) officers, I learned the unspoken hierarchy of service. The Army and Marine Corps maneuver troops killed in combat occupy the highest tier, then other maneuver officers who stand to do the heavy lifting in future combat, then it filters down through other Army and Marine Corps specialties, to other services, and finally to the broken-down, irrelevant has-beens like me.

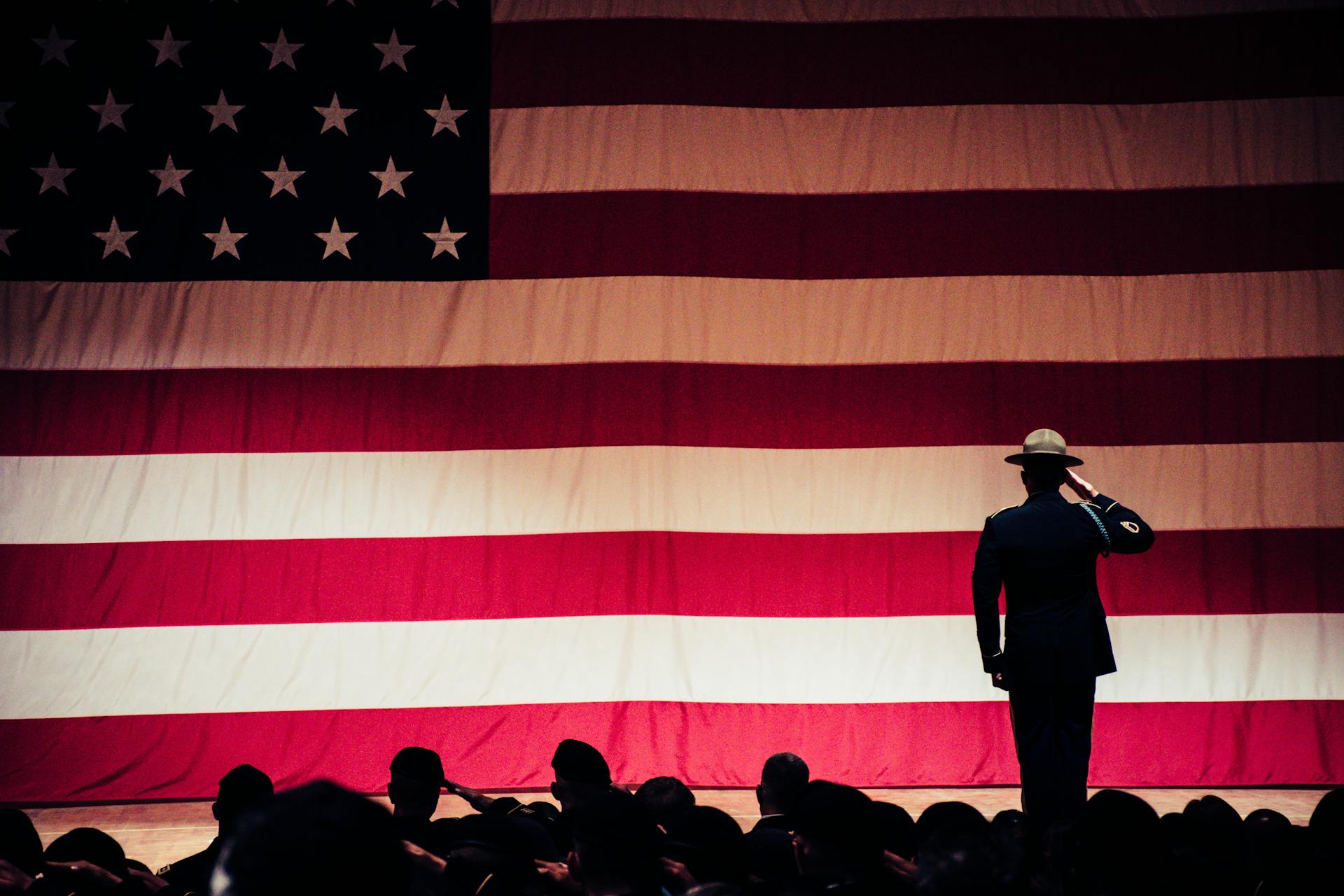

Almost all these boys in the hall were younger than me, and all of them were gone forever before me. They drew their last breaths in places like Diyarah, Ad Dawr, Baghdad, Paktika, COP Keating.

I wondered at the process for deciding what to include, thought how the families must have agonized over how to capture who their person was, to make him immortal, in 75 words or less. The circumstances of the death had to be conveyed, where he hailed from, who he left behind. So little time left to make him an individual. It struck me as one long continuum of ridiculousness: my service, theirs, the civilians who chirp, “Thank you for your service” and “Happy Memorial Day” unironically.

Most of us didn’t realize it was ridiculous at first, of course. We joined because we believed we were on the side of right, or our parents didn’t have money for college, or we felt like we’d be dead in a year if we didn’t get out of our Podunk hometowns. We decided to become officers because we thought we could make more of a difference that way. That, too, was ridiculous, and the entire system depended on our not realizing it was ridiculous until we were absorbed into it, until we became ridiculous too. By then, we were complicit; we were convincing the next wave of sailors and soldiers to buy the ridiculousness and upselling it with a side of apple pie.

If these boys could still speak, what would they say? Would they tell their replacements, the living, it was worth it? That they’re in a better place? That they’d do it again? I wondered what happened when the Army filled up the walls. How long could they hold the space before the next war started and they had to make room for the new boys?

I focused back on Jeff Toczylowski’s plaque to read the synopsis of his end-of-life story. He left $100,000 and instructions for a big celebration of life party in Vegas, in the event the war got him. At the time of his memorial plaque creation, New Line Cinema had bought the rights to his story, proposing to make it into a movie called Time of Your Life. The movie was never made, but I learned from the foundation page his family created in his memory that Toz would have disagreed with my assessment of how ridiculous it all was. In the email he composed to be sent by a friend in case he didn’t make it back, he wrote: “As far as I am concerned, we can send guys like me to go after them [terrorists] or we can wait for them to come back to us again. I died doing something I believed in.and have no regrets except that I couldn’t do more.” But Toz wasn’t here to see Afghanistan cave in, so it was hard to know what he’d have thought.

The urge to light a cigarette broadsided me, and I patted my pockets for the outline of a pack before I remembered I hadn’t smoked in over 10 years. I exited the east entrance and headed for the smoke pit. I knew it would be full of soldiers, and one of them would let me bum one.