This sad quintet was sucking life itself out of the jazz standards they probably meant to resuscitate.

The frenzied cymbal and snare work of the drummer had many in the audience worried he was suffering a seizure right in front of us. The upright bass player had forgotten or consciously chosen not to get in tune with the nearby piano, or any established musical key.

The band’s trumpet man faked muted trumpet sounds into a green plastic horn straight from some discount store’s toy aisle. He stared daggers through his discount sunglasses, too—daggers clearly aimed at the saxophonist, who introduced every song in a whisper, then just stood around nodding his head until it was time for him to squeal and squawk his next solo on his genuine instrument.

At the piano sat a one-armed old woman who looked like she belonged behind the church organ on a sinking pirate ship. Her arm ended in a silver metal hook, which drastically limited her harmonic possibilities.

So this was what it was like. I’d never stayed in a hotel with a band performing in its downstairs lounge.

There was no stage or bandstand, just this gang crowded around the piano in the corner. Hotel guests were crowded up against the bar in the opposite corner, doing our best to drown our sorrows, musical and otherwise, with bottles of lukewarm beer and mixed drinks that were little more than the thought of liquor splashed over a cube or two of ice.

From the agonized expressions I saw around me, the booze wasn’t getting the job done.

We were all hostages and knew it—of this band’s botched, back alley rendition of Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight.” Or were they struggling through some number by Dave Brubeck? It was impossible to tell. But hostages we most certainly were. The bartender had a handgun stashed under the bar. She brandished it at anybody who made a move toward the exit.

“Where you think you’re going?” she asked when I stood up from my hobbled barstool. “Unless you’re getting up to dance, sit your ass back down. I’ll loan you a cigarette.”

I tried to make nice, flashing her my best smile. “This band gets paid in tips, right? Maybe they should invest in a few music lessons.”

She scoffed, crossed her muscled, tattooed arms. “You wouldn’t laugh if you understood their aesthetic. They’re avant-garde. They’ve toured Europe.”

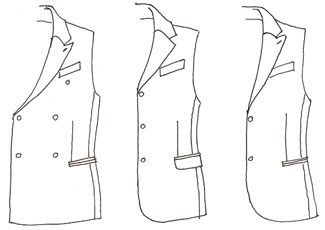

“Oh, I believe it.” I sucked down half a beer. “I’m much more sophisticated than I look. Seriously. You just see a middle-aged dude in a wrinkled tie, but there’s a lot more to me than that.”

“Keep telling yourself that if it helps you sleep at night.” She handed me my next beer. “You idiots in your JCPenney suits are all the same. The sales clerk insists Chinese suits are best because their little worms spin the finest silk. And you fall for it every time.”

The bartender chuckled as if she’d heard this story delivered a million different ways. “Thing is, losers like you don’t even deserve to hear this music. I’m doing you a favor.” She shelved her pistol and brushed her ragged pink bangs out of her eyes. “Your pitiful ass should be thanking me for booking these guys. But in an hour you’ll be upstairs in your room, jerking off to hotel porn, wondering if I wear thong panties or nothing at all.”

She shook out a second loaner cigarette. I fired it up.

“Not me,” I said.

“No, not you—of course not. That’s what they all say.” She wiped the bar with a towel, then nodded toward the band. “Ruth is the mother of the boys.”

“Excuse me?”

“Our little jazz combo there. They play like they’re telepathic because they’re brothers. Two sets of twins. Not identical, obviously. Ruth at the piano is their mother.”

At that moment, the one-armed pianist was jabbing at the black keys of the hotel’s baby grand with her gleaming hook. She missed more keys than she hit and didn’t seem to care, but the commotion the old woman created—the sound of mistaken trust in the stoned thugs accompanying her, forever innocent little boys to her—suddenly made sense to me.

Everything I’d ever feared came crashing down around my ears, considerably louder than the tuneless ruckus confounding my fellow hotel guests.

I’d returned to Ohio after two decades away because my own mother had died and couldn’t bury herself. I’d taken care of that fine, only I didn’t know what was supposed to happen next. Very little shit in life resolves itself like some perfect chord progression, let me tell you. There’s no escaping that fact.

Here’s another fact: I started crying. Tears poured down my face. I’d never considered myself a mama’s boy, but what I’d never considered turned out not to matter very much.

The bartender set a stack of napkins in front of me, then wandered off so I could blubber in private. That was the last I would see of her. I stayed put all night, comfortable as I could make myself in the shadows of my cheap funeral suit.

Whether that hotel band was playing a Duke Ellington ballad or some John Philip Sousa march behind their mother’s hunt-and-peck solo that night, I have no idea. Maybe it was their take on “God Save the Queen” by the Sex Pistols.

I guess I’ll never know for sure.