“It’s only two cells,” you tell your son.

The words land on the breakfast table even as your mind questions the absurdity of the statement. Wasn’t your diagnosis always in stages? But you have chosen this word to lessen the blow. He lays out his chubby hands on either side of his favourite pirates-themed divided plate, where you have laid out his favourite breakfast of dosa and chutney on his favourite dinosaur placemat. He doesn’t meet your gaze but traces the lines of a T Rex with his little finger. Your fingers itch to hold him, smother him with kisses, but nobody taught you how to talk to children about illness or changes in your physical appearance or the struggle. You draw a long deep breath, fill your lungs with oxygen, but he seems to focus on the dinosaur.

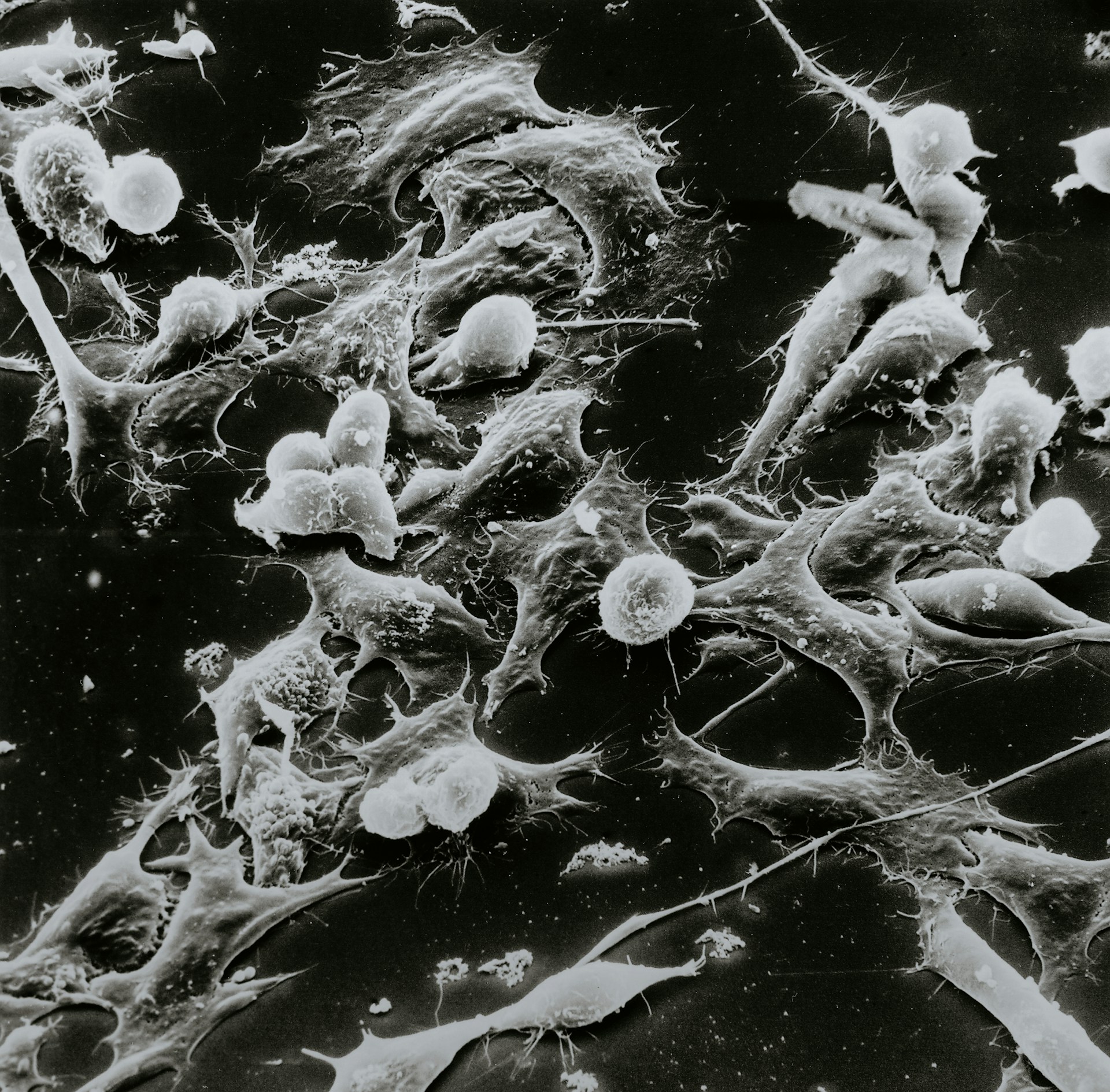

“It’s only two cells!” Your voice is louder as you replace the image of the thick mass of white you saw last week on the computer screen with two specks. Fog clutters, chokes, and drags you into a vortex when you watch his lips pout, face scrunch, and the next moment, the chair screeches, drags, and sways on its hind legs.

“No!” He screams.

The air-conditioner hums, birds flit around, a road-roller groans while fixing the sidewalk, and life goes on as yours takes a detour. You squeeze the edge of your t-shirt, wondering about your next move.

His blue-framed glasses stand crooked over his nose. His cheeks are already wet and his perfect pointy nose is leaking. He takes two, four steps, backing away from you, shaking his head, and the jagged edge of the knife sears through your skin.

“It’s only two cells gone wrong!”

A crater has deepened in your chest. Hot breath flares your nostrils and your toenails grate the cold floor. You stick your hand out, hoping to reach him, feel him, hold him even as your brain wonders if that is the right thing to do.

“No. No. No.” He moves away from you, flailing his arms and shaking his head. You see the limp dosa, the growing distance, the failing health. All you want to do is punch the air, scream your anger, but you blink away your tears. He inches closer, his pink lips tremble and his dino t-shirt has mucus.

“It’s only two cells, baby!” All the words you had rehearsed the previous night evaporate. For the hundredth time, you wonder if your face defies what and how your pit feels.

“Breathe!” You lock your fingers and think of ways to please him, soothe him. Maybe make his favourite chocolate shake or offer cookies for lunch? Or let him watch his favourite show for an hour or hand him the Nintendo remote? Indulge him?

“Is it only two cells?” He sniffles.

Your vision blurs and your head swings. You pray it is a bad dream, a toggle button that can be set right, but the piece of your heart you have tried to protect tips his head and sniffs. You open your arms and wait to feel the warmth in your chest. He takes another step. His face is stained, pained. The essay on ‘How to talk to kids about illness’ blurs in your memory. Was it about sounding positive, gentle? The script is mangled, crumpled.

“It is only two cells.” Your voice quivers so you clear your throat.

You count the ants that are trailing the floor even as the long road to treatment the doctor proposed is lifting its ugly head. You still can’t believe that the routine annual check had taken a different turn. Talking to your 10-year-old was never in the plan. You lean forward, eager to close the gap.

You use pet names. “Kanna, Raja…” You think of talking about science, in particular the advancement of science, the research, assure him of health, but the pep talk lingers on the tip of your tongue, refusing to slip out. He is within reach. You want to fly, take him somewhere safe, away from everything, but all you do is take his hand in yours. A faint glow slides in the corner of his eyes. The tension in your pit eases. You had worried about questions. He had always asked the right ones. “Will he read those books? Google it?” You wonder. You dread. All you say is, “Just two cells. I promise!” He slips into your bosom and you hold him praying to every known force in the universe to make it real – just two cells gone wrong.