Lovemaking is radical, while marriage is conservative. -Eric Hoffer (1902-1983)

He smelled. I guess we all do, but he smelled different than other men I’d been with in my short, unsatisfactory (in that there was never enough and that I had so much to learn) sex life. He smelled like a blonde, it was imprinted on me that this was a smell I could live with, could caress, stroke, push against, bite, listen to (the sounds of the lake shore). He smelled, and I would watch him lie there afterwards, after we’d separated, the slippery sucking sound of sweaty bodies pulling apart, him on his stomach, the dent his spine made in the pale skin of his back; it smelled, and it was a river, a channel, a pool. He smelled like a child smells after playing outside all day, before the child’s mother insists on a bath. He smelled like milk (a scent that blond men seem to carry with them). The long hair around his face damp against a cheek, red lips parted in sleep (how he could fall asleep like that, so soon after orgasm, the air out of a balloon, pffft).

I never took him anywhere but home to the mattress on the floor of my dark, half-painted gray apartment (a paint job that I did not complete until I moved out a few months later), clothes strewn from the living area to the dressing room and into the bath. I gave him a key and I would come home and find him in the tub, milky water lapping at his milky skin (skim milk with its blue tint), his hair plastered to his head, just like after sex. The freshly-fucked blond man in my bathtub would stand up and step out of the water and onto the black and white tiles, draping a towel (was it threadbare? It could have been, I was poor and struggling to make it on my own, too proud to ask for help, back then at least) over his mid-section, a useless privacy screen. He’d cup his balls with a towel-clad hand and wipe under his ass with the other end, all the while leaning forward to kiss me in that drunken way he had, his pale skin lit from within and glowing in the dark bathroom, its window high up the wall, painted shut.

He’d find me sitting at the bar, come up behind me before I had a chance to notice him, lean in and kiss my neck, smelling of Jack and coke, the wind off the lake, his big soft chest pushed against my shoulder blades (a Renaissance nude, he was that luscious with his golden trail of hair that led down from his navel to his yellow nest of pubic hair—those red lips against that pale skin, an occasional blush from the chill of the night on his cheeks, the sting of my hand reddening his ass or the place where my hands had gripped his ankles as I sank into him, a bruise, rising.

He was a drunk (I may have been one too) given to rages, weeping uncontrollably, a sudden shower and I would walk away from him to the other end of the bar, cross the street to get away from him, stand up suddenly and dump his ass on the ground after he had sat in my lap begging me to hold him while he shook, convulsed, and again that beautiful golden hair stuck to the side of his face, this time with the salty tears of a weeping child, an aphrodisiac, nectar that I would lick away, then start kissing him, forcing my tongue into his mouth and we’d grapple with our clothes and roll onto the mattress on the floor and fuck.

I believed I was in love; it’s too shocking not to have been true, but I did not see us in that forever dream I was trying to form (and deny at the same time) in my mind’s eye of what love could be between two men. The act of sex was our commitment. It would have been obvious to you that we were doomed, but the haze of booze the heightened reality of my dependence on the tiny, powerful “white crosses” (amphetamines with a jar all their own), the smoke from cigarettes, and the dawning of the age of Aquarius, the dreams of our parents, buried in the backyard next to the last pet parakeet.

His smell, though, was enough, for the little time we had, and there was some joy outside of the bed, outside of our fucking. I’d come back to my apartment after my morning classes and before I had to go to work in the evening waiting tables, and he’d be there, sleeping off the night before, and I’d strip down and slip under the blanket next to him, my thin, angular body folding into his. He’d push his ass against me and guide me, take me by his hand and show me how much he wanted me, and we’d end up in the bath together later, smoking a cigarette (or maybe a joint), a glass of wine—hell, a glass would have been too good—we’d pass a bottle of cheap wine back and forth while we wiggled our toes against each other’s backs. It worked and it was heaven, my own personal revolution.

The out-of-doors changed the way he smelled and because we were so often walking home in the deep, late darkness of the early morning, after our local bar had closed, we’d hold hands and walk down the middle of the street, stopping under a street lamp and mash our lips together. I’d grab his beautiful golden head of hair in one hand and pull his face up to mine, his blue eyes crossed to see me straight on, his cotton candy mustache so soft and slightly immature. He had little beard to speak of, so his attempt at a mustache was half-hearted and endearingly teen-like. He was so young and fair, my blond man, mine.

We didn’t cohabitate. I never knew where he lived. Or have I forgotten? I know nothing of his life before we met and certainly not after we parted. I believe he had a job, or it’s quite possible that he was hustling ,and I was a convenient resting place between tricks, which is more than likely—times being what they were—and don’t be surprised that I tried it myself, but I was rotten at it; I had too many opinions and too much to say, but hustlers were common in our little corner of Chicago–many men were too afraid to live openly as I did and so they’d cruise around and around and around and there was money to be made. It was a living for some; it was not liberating; it was a retreat, society created cowards of us—all that was missing was the white flag of surrender.

Jamie. I have not used his name yet, I hope you don’t mind, but I think it’s time I said it out loud—as loud as I can say anything, typing. Jamie, it was the perfect name for my blond man, muscular and smooth (j), soft and pliable (m)—the vowels, a chain pulling at my cock. He was a drunk, an addict, an incredible fuck. Nearly as tall as I, but diminished by his spirit and his life, his loneliness plastered across his brow, indistinguishable from the locks of golden hair turned dark with the sweat of love-making. I would push them away and look at him; he was not afraid to look back at me, and I would lean down into him and mash our lips together, the sudden darkness of a kiss wiping away his fear (from my sight).

We argued one night walking home from the all-night grocery store; he, a few yards in front of me in the middle of the street, looking over his shoulder at me, yelling. I threw a small jar of mayonnaise at him, 16 ounces flying through the air aimed to hit him in the back of his head as he ran ahead of me down the center of Surf Street, my aim never so good as then. The jar, though, hit the street with a very pleasing explosion of Miracle Whip, the shatter of glass diminished by the glop of sauce, the metal lid rolling off under a parked car, the echo of its wobbly spinning, fading as it came to rest just as I had, watching him run down the street and turn onto Sheridan Road and out of my life, our last orgasm.

He did not come back. I never came home again to find him soaking in a tub of milky- blue water, his cock and balls floating just under the surface, rising and falling with his breath, his sweet laughter and sour breath, his insistence that I join him, reaching out to take my hand and pull me into the water, fully clothed, kissing me as water splashed out of the tub and onto the little hexagonal black and white tiles. He did not come up behind me at our bar, just a couple of blocks from my apartment and put his arms around me, kissing my neck. I did not see him at any other bar or walking the streets in Boy’s Town; friends saying, “just as well; it wasn’t meant to be.” I made an attempt to be morose, forlorn; my lost-at-love look was a work-in-progress, one I would refine over the next few years, after a succession of failed or aborted relationships.

I had dreams that a boyfriend would mean an 8 x10 photograph framed and on the mantle, whether there was an actual mantle, it did not matter. I dreamed that its full-color glory would be the affirmation of the success of the revolution and that somehow my normal would be the normal. As impossible and irrational as that thought might have been at the time, it was one that I held onto. I could not have said this then, but I felt it, as an animal instinct, printed on a gene somewhere deep along the curves of my helix, yet to be discovered.

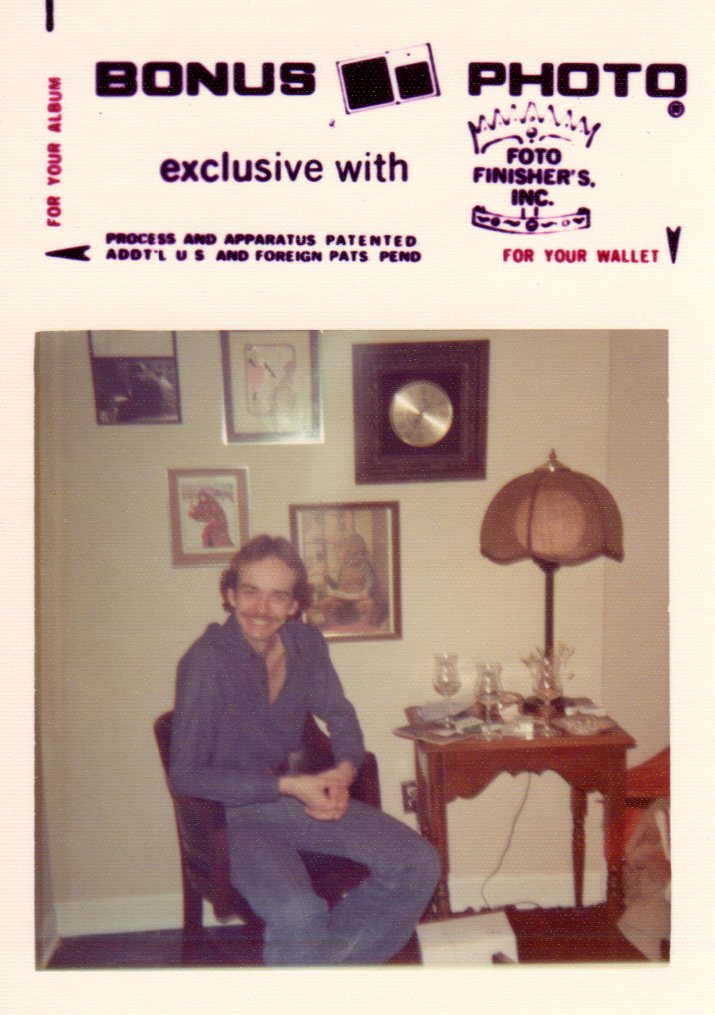

But instead of the 8 x 10, all I have to show for that time is a wallet-size photo of a young man taken a few months after the facts (and fiction) of this story, taken in the home of friends who knew Jamie and our time together. A photo to remember what it was like, fighting the good fight—it was a good fight, that love-making time. If you put me in your wallet, will you remember how radical our act of making love was?