Round Table is a new feature where members of the BULL team get together and talk about what’s going on in the world.

On today’s episode, Editor-in-chief Jared Yates Sexton sits down with Christopher Wolford and Jim Warner to discuss the death of Prince:

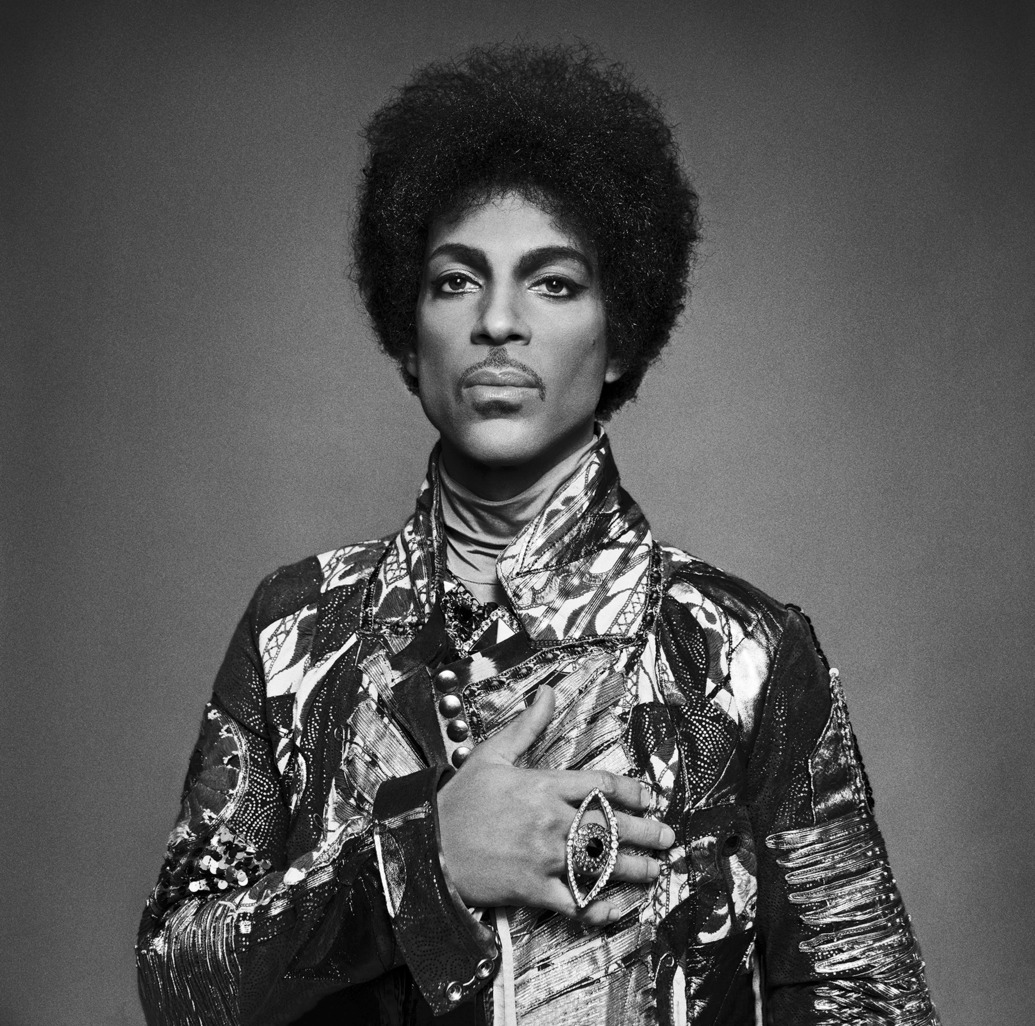

JYS: Fuck. Prince died. I’ve been checking the Internet every twenty minutes or so and hoping there was some kind of mistake. It felt a little like a hoax, or at least a misunderstanding, and I’m wondering if maybe it felt that way because…it’s Prince. The guy didn’t seem like he could die because he didn’t feel real.

Prince died. What the fuck.

JW: What’s kind of remarkable–considering how much Prince is trending everywhere–is how mysterious Prince has been able to be in light of social media. Granted it’s been only a few hours since his death was announced, but the lack of information we have about Prince is pretty amazing. There was always a sense of distance with Prince: a public recluse. He’s one of those rare artists who spoke directly to his audience with his art. He didn’t need Twitter or Facebook or IG. He had removed himself from the 24 hour TMZ cycle but still remained relevant. In a lot of ways, that sense of freedom and autonomy is unheard of–maybe Bowie came close to the inaccessible/accessible artist.

CW: And like Bowie, I think one reason fans never needed complete access to Prince’s personal life was because the music was always enough. You could keep coming back to it and finding new things to explore – new sounds, new ideas – all uninfluenced by some all-access version of the artist in your mind. You could experience the music in a pure, unadulterated way. Something that is near impossible to do in this day and age, especially with artists who, often out of necessity, have to provide constant accessiblity to promote their work and maintain a fanbase.

JYS: I think one of the most amazing things is that Prince wasn’t always on the cultural map. Like, I remember him disappearing for years only to be mentioned in Today Show segments that were like, Prince changed his name to a symbol, or, the Artist Formerly Known As…. It was a lot of reinvention and culture didn’t necessarily buy into it, or didn’t celebrate it, it was more like a, okay, here’s where Prince is and here’s where we are, and those two things are more parallel than intersectional.

What’re your favorite tracks, Prince-wise? I’ve always been a big fan of “1999” but the one, for me, is “Raspberry Beret” with its storytelling and the interchange between the strings and his trademark whine. I think that’s what I imagine when I think of Prince…

CW: I didn’t really delve into Prince’s catalogue until I was in high school. I had heard the hits, of course, but not much else. And then I watched him play “Fury” on SNL in 2006. I’d always known Prince’s vocal chops were top notch but that guitar playing was something else, something unworldly. Pure funk dripped off of every riff. After that I was hooked.

JW: Before I discovered punk, or college rock, or rap, one of the first things I discovered was Prince on MTV. I didn’t have the language then, but I know now what I was drawn to and it really shaped who I became. He was so singular, an individual at a time on television where there was that resembled diversity. I know that most argue Michael Jackson ushered in the era of black music on MTV; however, Prince wasn’t just soul or funk or pop music. Like Bowie, you can hear him in everything that has traveled in his wake, but unlike Bowie, you can also hear everything which predated him in rock n roll. He was a reminder that guitars and groove and rebellion came from Little Richard and Chuck Berry (as much as if not more so) than from Elvis. It wasn’t just racial, it wasn’t just sexual, it was something as unnameable as the symbol he chose to in response to Warner Bros.’ artistic slavery.

For me, it’s all right there on the cover of Prince’s Dirty Mind album. The black bikini-clad star in assent stares with hunger right through you, and while it’s easy to get lost in the look he gives, it’s the rude boy button on his lapel which gives him away. This is as much punk as anything The Clash cut for London Calling, and in many ways it was where Joe Strummer and company were heading towards for Sandinista! or where Bowie would take his Thin White Duke persona a few years later for the MTV generation. But here’s the difference: Bowie was the quintessential chameleon and Prince was the ultimate synthesizer. That’s not to say one or the other is more important or influential, but it does speak to how each took in the world around them.

JYS: That’s interesting, Jim, because as I sit here and think about my first experience with Prince it had to be his “1999” video and, in the wake of that, I had to do a lot of soul-searching regarding what I thought to be the dichotomy of gender and sexual roles in America. I must’ve been eight or nine maybe, and I remember, at first, thinking, holy shit, this isn’t okay, there’s obviously a problem with this, and by the end of the video I realized the problem was with me all along. He really was a reality check, or rather an omen of things to come that changed how people viewed society and individuals.

There aren’t many artists who can claim the same. There are writers and poets who called into question the tenants of life, but it’s popular artists, and popular acts like Prince that really did this in such a widespread way. I’m watching his videos, listening to his songs, and it’s the complete package. The pop genius, the virtuoso performances, and the power of the individual. It’s all such an ungodly combination…

JW: Rolling Stone’s Anthony De Curtis was discussing the aspect of the virtuoso yesterday on Sirius XM. Usually when you have a musician recording all of the instruments for a record, there is a sense of production which is lacking–that chemistry which comes from a band dynamic takes some of the spontaneity out of the performance. Prince was such a studio genius that there was never a sense that it was a one man band. Again, going back to Dirty Mind, he is playing everything as if he was able to fully divide his identity into the components of a band. I don’t know if anyone (with the exception of Stevie Wonder) has that ability within them. It’s a slight of hand at the mixing board, but it’s also something intangible. There’s the real mystery with Prince–not the recluse or the symbol or the hours of unreleased music yet to see the light of day. The true mystery is how he was able to be so artfully articulate his message in music.

CW: Obviously for those of us that grew up with Prince’s music, we have forged these deep and real connections with the artist and his music. I’m curious to know, since the two of you are part of academia and are around a younger generation who may be less familiar with Prince, how have they reacted to the news of his passing?

JW: I was actually heading to class when the news dropped on Twitter. A couple of my students knew it was a big deal and were familiar with Purple Rain or his Super Bowl performance a few years ago, but there was a lot of ambivalence as well–much more than when Bowie died earlier this year. I think part of it has to do with where I’m teaching. While Knoxville has a liberal streak in it, I’m teaching in a conservative East Tennessee suburb. That said, the students who have already begun to face identity struggles here were very aware. What will be interesting is how the narrative moves forward when we discover the cause of death. I think those of us who are directly in touch with a younger generation need to define context for Prince.

JYS: My students are less familiar with Prince as an artist and more with Prince as a concept. Or rather, the unbelievably talented cool guy who owned every room he walked into. I think they’re more in tune with his ability to personally brand himself, a concept that was incredibly foreign years ago but so commonplace now. The stuff he did, in the studio and out, the melodies and the gender experimentation, are still echoing in music and culture, but I’m not sure he gets all the credit he deserves.

I will say though, I’m looking forward to all the Prince samples that’ll undoubtedly be coming down the pike. Those tracks are going to serve as a basis for the next few years of hip-hop and I think that’s going to be incredibly beneficial.

JW: It’ll be interesting what will happen with Prince’s music in the coming years. For someone who had exerted/championed artist rights, I wonder who will have keys to the kingdom? It’s the reason why Prince isn’t all over Youtube or Spotify right now. On one hand I hope we hear this vast archive of music, or that he’ll be sampled and dropped into rap beats, but on the other, I don’t want his work to be a product of the cash/smash/grab. Regardless, his impact will continue to resonate, across genre, identity, and culture. Even if he’s not name-dropped, or heavily sampled, again, Prince’s music is a summation of everything that came before him and what will be produced in his shadow.