There’s not much I haven’t already said about Sheldon Lee Compton, so I’ll just some it up with this: He is one of the best storytellers out there right now.

If you don’t believe me, go read his collected stories.

There’s a wisdom and humanity to his stories that feels like it’s been aged for hundreds of years, but here he is still alive and kicking and churning out the Gospel of Sheldon with every year that goes by.

It’s weird that this our first actual interview, since I feel like Sheldon and I have been interviewing each other for years—mostly me trying to pick his brain for some of that wisdom and humanity I struggle to find sometimes.

And yet, for all the emails back and forth and for all the stories I’ve read of his, I still felt like I was only skimming the surface.

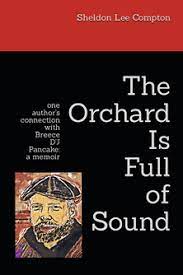

Which is exactly why I was so excited to read his book Orchard, part memoir and part biography of Breece Pancake.

Like a lot of us, for me the legend of Breece Pancake was the wunderkind who wrote a pièce de résistance of short fiction and then sadly committed suicide. In many ways the epitome of a tortured artist gone too young.

I must admit that, much as Compton does acknowledges in Orchard, my first draw to Pancake was the legend. In so many fucked up ways, that was the legend that I had set out for myself when I first started writing: to write one great book worth dying over.

To write my own ending.

A book as suicide note.

There is an allure to that. And sadly I spent most of my twenties and thirties imagining how people might excuse my personal shortcomings and elevate my writing if I were to kill myself. If I could come up with an autobiographical footnote that would make people forgive my not-so worthy suicidal writing.

In Orchard, Compton takes this mythos around the suicidal author and turns it inside out. Compton draws from his own brushes with death and trauma and the loss of loved ones to take away some of the romantic notion of the trope of the tortured artist. But at the same time, he elevates the true tragedy of Breece’s suicide in the greatness of his work and the work that he never produced and even more importantly the impact that Pancake had on nearly everyone he touched.

It’s the questions that Compton raises in Orchard that make it stand out from your typical biography and memoir. It’s his willingness—his wisdom—to simply explore those questions without needing clear and clean answers. Compton is not writing an academic treatise dissecting what made Breece do what he did and how this all made his work as brilliant as it was. Compton is writing with the understanding of the messiness of the human condition. Compton is writing about a troubled man with an incredible talent that more people should know about—not because he committed suicide, but because he was a supremely compelling, extremely “human” character who happened to be full of contradictions and no easy answers—a human who left behind so many friends and loved ones who would probably give up all his writing to have him back.

wisdom—to simply explore those questions without needing clear and clean answers. Compton is not writing an academic treatise dissecting what made Breece do what he did and how this all made his work as brilliant as it was. Compton is writing with the understanding of the messiness of the human condition. Compton is writing about a troubled man with an incredible talent that more people should know about—not because he committed suicide, but because he was a supremely compelling, extremely “human” character who happened to be full of contradictions and no easy answers—a human who left behind so many friends and loved ones who would probably give up all his writing to have him back.

Part of what makes Compton’s writing so good is that he is always able to break down the most complicated truths of life into the most elemental ideas: there are no real answers in life (at least until we die), there are only the questions worth exploring.

Here are some more of those questions I got Compton to explore with me:

BKD: Talk to me about the origin story of this. Were you always planning to write it as part of your own story? Besides the natural curiosity about Breece and his suicide, what was it that made you want to write his biography? How much did the final product evolve from the vision you had from it from the start?

SLC: The first day I found out about Breece I was working as a newspaper editor. A reporter and I shared an office. Jarrid Deaton. I always mention him by name because, well hell, he literally set me off on this path.

One day when news was slow (we always surfed Wikipedia during down time) Jarrid called over to me. “You ever heard of Breece D’J Pancake? He was this writer from Appalachia who was super good and was starting to take off.” He stopped, and I waited. I could tell there was at least a little more. “Oh, man, he killed himself in his twenties.”

From there I decided to write my critical thesis on Breece for my graduate degree. I later published the opening section of the thesis at a blog I was running at the time and a guy by the name of Derek Krisoff sent me an email. Derek was the director of West Virginia University Press (Breece was from Milton, West Virginia) and asked if I’d like to write a book about Breece for them.

Well I was pissing myself I was so excited to say yes and get started.

Thing is, as I got into the book those parts of me started filtering in, and I did nothing to stop it. Before long I realized I was writing this kind of biography/memoir mash up. The press had me do five rewrites before my editor there finally said okay let’s take it to the board and see if it’s okayed for publication. I didn’t even know that was something that had to be done. It’s a university press, and they evidently ain’t much on hybrid memoirs. Go figure. So they voted the book down and I took the manuscript to Adam Van Winkle at Cowboy Jamboree Press and he was happy to put it out. He’s been a huge champion of that memoir since the first hour until as recently as this week, singing its praises across social media as the best writer memoir he’s ever read. I love Adam, man. Guy puts everything he has behind compositions he believes in. Cannot ask for more than that because there’s nothing more to give. That’s everything.

BKD: Writing a memoir and making it worth reading is one thing, but then there’s writing a memoir in which you are drawing parallels to one of the great writers of our generation. Did that feel like a lot of pressure? Especially when you yourself acknowledge that you don’t really suffer from suicidal ideations and don’t have many close acquaintances who have killed themselves, what was your strategy to make these stories go together?

I find it hard enough to put your own bullshit out into the world without actively inviting the comparisons?

SLC: You make a great point. The comparisons were not welcome or unwelcome. The truth is, I never thought about it until now. I’ve been self-disclosing material for so long, I guess. Not sure, really. I had written nonfiction very little before Orchard. A couple essays I thought were pretty good and had published, but that was it.

I had some reservations in some sense, yes, because I have no personal history of suicide attempts (unless you count drinking everyday for twenty years and smoking for ((at present count)) ten years after having a massive heart attack). But having watched my father actively disregard even more warnings than that, I felt I could recognize the yearning for death well enough to start looking closely at it in a book.

And, again, my strategies are so instinctive with writing I’m not sure I had ideas about how to make the various stories throughout the book connect. I wrote, and if they connected I didn’t spend time rewriting those sections; if I wrote and they didn’t fit, I gave a little attention to that. But overall I trusted myself in about every aspect of composing the book. I don’t really know how to write any other way. I’ve just recently had some luck planning a book with this new novel I’m working on, Oblivion Angels, but that’s something I’ve learned over the years and a few novels in: ideas while writing about where the story might go is a moment, like a lightbulb moment, when I know I should write it down. With this novel-in-progress, those times I’ve jotted down an idea for the story have formed into a loose outline. I say loose because I only jot down an idea. I allow for my instincts to flesh that out and get it in chapter or section form. It works out most of the time. I have to do that because without the fun of discovery, I wouldn’t write a word ever again, of that I have no doubt. Because goddamn, ain’t none of us making money off this, and I never planned to.

BKD: I feel like every book I write is basically a question that I set out for myself to figure out in the process: Why do I have these issues? Why did my family have those issues? Why do I have to write this book? Why can’t I just suck up my shit and act stoic like the rest of my midwestern/Scandinavian people?

I know that we’re kind of different this way, but I was wondering with the memoir and being forced to confront the facts of your life head on, did you have any revelations? Was there anything where you kind of evolved on? I know at the heart of your own sections there is a lot about you struggling to cope with your father’s decisions and also struggling to cope with the idea of anyone giving in to “giving up”? Was this something you had already reconciled with before you wrote this or was this something that you were still wrestling with throughout the book?

SLC: I don’t say this to impress anyone at all, only as fact: I’m a survivor plain and simple and have been since I was seven years old. I spent my childhood dealing with the highest level of mental, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse at the hands of a cousin five years older than me. I learned during that time that giving up ended in only one way, or at least the one way I thought at the time, and that was dying. For six years I spent nearly every day waiting for when he was going to jump out of a closet and put a forearm into my nose, grab me and tie me to the coffee table and hold me at knifepoint, catch me sitting in the floor watching tv and sneak up behind me, grab me by the hair of the head and slam my face into the floor. It never ended. And it put me on the alert, walking around landmines and watching for snipers.

So even the faint idea of giving up the will to survive is sincerely both appalling and disgusting to me. I know it shouldn’t be. I should have the sympathy to understand how difficult it can be, how a body can just decide it has taken enough and wants to move on to whatever’s next. But both my sympathy and empathy buttons were severely damaged during this long period of abuse. I was diagnosed a couple years ago with Complex-Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome and Borderline Personality Disorder (the BPD from the near constant need to dissociate from my reality). I learned that C-PTSD developed through prolonged childhood trauma, unlike PTSD which arrives following a single incident such as a car wreck or the sudden and violent loss of a loved one. Neither is worse or better than the other, just differently developed.

How I became the fucked up way I am is something I understand better now since getting into therapy. But the mystery of how my father and my cousin became what they were is and will always be an unknown for me. I can’t imagine ever figuring that out, though I did try to compose a fictional exploration of my father’s origin story with a novel called Dysphoria. Hell, I mean why not? I’d already done that with a couple dozen or more short stories. He’s dead now but when he would still read my work he said once, “Lee, you’ve killed me a hundred times in your stories.” I had nothing to say to that, and no urge to.

The revelation that came to me is the same one that came to you, my friend. I spent a lot of time writing about shit that I really had no idea about but then I read Breece’s stories and it sparked something in me. I wanted to write about the strength of my people, Eastern Kentuckians. We’ve been, and will continue to be called, dumb, backward, incestuous, lazy, drunkards and drug addicts, and on it goes forever. There is no movement for us; we’re one of the last cultures it’s perfectly acceptable to be subject to unapologetic bigotry. Pisses me off at a fire-and-brimstone level. And I took that pissed-offedness and Breece’s abilities as a writer and busted ass to show our heart and loyalty and ability to survive hardship and a hundred other positive traits. I’m still trying to bust ass with that as much as I can.

BKD: You draw a lot of parallels to your own experiences feeling like you didn’t fit in at college with the way that Breece didn’t seem to fit in at college. But then there’s the other side of it of never really feeling like you fit in at home either where you are at heart a writer and a reader of literature.

For me, growing up on a farm in northern Wisconsin, I never fit in with the farm crowd. My brothers and my dad could fix anything that had gears whereas I often stayed inside to clean the house (or rather say I was going to clean so I could watch cartoons). I wanted nothing to do with being called “farmer Ben.”

Then when I started playing sports, the last thing I wanted to do was admit I found therapy with writing. In all honestly, I would’ve never told anyone that I wanted to write. I spent most of my young adult years trying to beat the sensitivity, the desire to write about my feelings out of me.

Of course, then I get to college and I don’t fit in with them. I am the “redneck.” I’m the kid who grew up on the farm in bumfuck Wisconsin and raised sheep for 4H. Which I didn’t tell anyone about.

It wasn’t until grad school that I realized the only real thing I could write about were all those dirty little secrets about my childhood.

How much of this damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t identity has shaped who you are as a writer? As a father? As a man? (Not just the redneck versus collegiate, but also the artist versus the manual laborer, the empathic/sensitive kid versus the stoic? etc.)?

SLC: Man I spent a lot of time beating myself up about being a hillbilly. This was especially heightened while in grad school. But a lot of it was internally because people were kind enough to me, never put me down because of any perceived lack of intelligence, always complimented me on my “southern” accent, and so forth. In the fiction workshops I was treated with the same respect for the most part. The very first workshop was kind of rough is about all. But once they saw I could write, that improved. Like I said, it was all my own lack of self-confidence that I tortured myself with. So I drank a ton while at residencies, spending upwards of $600 at Louisville’s Brown Hotel’s bar each time to tamp down that fear and nervousness. I was never anything but drunk during workshops until my final semester. I managed to wait until late afternoon before drinking there at the end.

But, yeah, I’ve never felt like I fit in. Eastern Kentuckians ain’t uneducated or dumb at all, but they don’t read a lot or write sonnets. It’s a certain hard kind of culture that academics don’t necessarily factor into much of the time. It’s not prejudice against poets or writers, it’s more about not relating, I think. But I’m not sure honestly. I do want to say, though, that those of my people who have read my work have had a lot of good things to say about it, with most of them becoming regular readers of mine. Thing is, I’m not so sure some of them even realized people wrote stories or novels about them and the things they’ve gone through or accomplished or, probably most importantly, survived. They would have, consequently, felt no real reason to read without that connection, maybe.

The result is that I haven’t felt like a big part of my culture for as long as I can remember until somewhat recently. In the last five years or so I’ve grown into it. I farm, do a lot of carpentry, work on cars, fish, and generally take part in a lot of activities that have endeared me to my people. I still don’t talk about having books published and so on. People have always been complimentary about that sort of thing in my area but, again, it’s a matter of relating to each other. It is saddening sometimes that I’m kind of landlocked that way, but at my age I’ve come to terms with it and try to spend less time dwelling on it.

BKD: It seems like one of the main themes of the book was realizing that there were no easy answers. There wasn’t that one specific document that you read about Breece that revealed his innermost thoughts. You weren’t able to really get to the place where he lived at the end, and anyway the orchard was gone. I imagine that must’ve put you in a kind of anxiety-provoking place where you are writing a biography and there just doesn’t seem to be enough to really get into his life and draw out a lot of revelations.

But in a lot of ways, I felt like this was maybe the most authentic conclusion. Having my own brother kill himself at 18 and not leave a note and having lived a very reserved life, his story was just never going to have any good answers. And any answers I tried to provide just felt bullshit and projections of my own bullshit. Even though I’ve written about him mostly in fiction, the truest endings I’ve been able to come to are simply that there are no resolutions to find and that will probably always haunt me. Hell, I don’t even know how he killed himself, and at this point I could probably find out, but in some ways that wouldn’t be true to my own version of things.

How was it while you were wrestling with all this stuff? Were there ever moments where you felt like you were failing your job because you couldn’t uncover the big revelations? And how did you get through all that?

SLC: Goddamn I’m sorry about your brother, Ben. I lost mine to a car accident back in 2008 on Christmas Eve. I don’t think about it each and every day but I do think about him no less than once a week ever since. It’s a strange kind of loss, a brother.

But yes I struggled with the general incompleteness of my search and the resulting book. I wanted so badly to find the orchard, some version of it at least. I wanted it so badly I started having to ask myself, “Do you want to find it because you loved Breece and want to see it or do you want to find it out of a sense of morbidity?” The conclusion, as is the usual for me, was a little of both, if I’m being honest, and I’m always trying to be honest.

The worry about material and what I actually had for the book started right at the beginning though really. I’d written the essay, which was solid, but when they pitched me a book, my mind went right away to the fact that he died really young and had just started his literary career, the spotlights for the book I wanted to write. He was just a kid, not even thirty. He’d taught a little before he started getting published, there were some reflections and information I had found from his letters and even a few rough draft stories I hadn’t seen before getting into his archived collection at West Virginia University. I’ll always remember his bible with so many places highlighted and bookmarkers and thoughts written in the margins. It’s when I really and fully realized how much spirituality factored into his stories. This wasn’t necessarily a galloping shock, considering his fervent devotion as a catholic in his last years, but it did strengthen that part of his character for me. The catholic thing never made sense to me—before or after writing the book. I can speculate, but how in the hell does a boy from Milton, West Virginia get to the place in his life where catholicism begins to work so strongly on him? I’m not sure anyone, no matter the level of research or immersion into his life, will ever fully understand.

It turned out, though, that I did feel there was enough material from such a short life. I didn’t think that would be the case when I first started the book. But what buoyed it was the huge void left after his death. The absolute mystery of it. And often a mystery is enough to keep a writer busy for plenty of time and then some.

BKD: At the end of the book, you end up “creatively imagining” Breece’s last moments. I always think it’s interesting to read nonfiction by fiction writers vs. poets vs. straight nonfiction writers. Obviously, I feel like fiction writers tend to focus on story and narrative and scene whereas poets often find little moments and bring in lyricism and poetic jumps whereas straight fiction writers are often focused on the asking of questions and ruminating on the significance of the facts as they are as well as the facts that are unknown.

I know you do some great poetry but tend to predominately write in fiction. Did you set up any parameters as you were going in about “not letting the facts get in the way of a good story” or vice versa? Did you find yourself focusing on making the facts fit a narrative? Did this process challenge and maybe alter somewhat your approach to writing as whole?

SLC: That beginning section and end section—as a whole a single short story—remains my favorite part of the book. I’d written a version of this once before and saw it published somewhere. The story was written, but I took it and diced it some so that it hummed the way I needed it to for the book. And the bookending was a quick decision. I wanted that affect I’d read in books before, a clear beginning and end that tied in a way that would be as satisfying for the reader as it would be for myself. Not to mention that I kept seeing, as morbid as it may be, Breece’s head shattering from the blast, kept feeling how every time I imagined it my heart felt pure mystery as a newfound emotion. That shattering was always a bright, bright red, and since I have redbirds in my fiction pretty often without planning it, I wanted to describe it in the way I did.

I’m rarely ever concerned about making the history match the narrative. Once I take from a source, it’s mine; I can absolutely do what I want with it. I’ve faced no litigation or sleepless nights up to this point and doubt I will. What team of lawyers gives two shits about what some writer in Eastern Kentucky is putting into a short story? That number would be a solid zero. Zero people. So I make jumps, I take time to, like you said, push my way into a poetic lyricism, something I read a long time ago in Michael Ondaatje’s books Coming Through Slaughter and The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. I saw Ondaatje do the same thing with genius effect. I wanted that with this book—part research and part love poem to Breece. The first chapter and last chapter was my chance to do that, and I grabbed it up.

BKD: One of my favorite stories is “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood, which ends with the following:

You’ll have to face it, the endings are the same however you slice it. Don’t be deluded by any other endings, they’re all fake, either deliberately fake, with malicious intent to deceive, or just motivated by excessive optimism if not by downright sentimentality.

The only authentic ending is the one provided here:

John and Mary die. John and Mary die. John and Mary die.

Based on your own experiences with death and your research into suicide for this book, I feel like you would be supremely qualified to talk about how death shapes our narratives—both our own, as told by others, and the narratives we tell of our loved ones who die.

On top of writing about my brother’s suicide and my own suicide attempts, I’m always leery of post-death narratives. That’s probably one of the big reasons I watch True Crime—is to see how these people talk about their loved ones who die and their loved ones who kill other loved ones. Because for suicide, it’s kind of both. My brother was both a selfish asshole and a traumatized kid who couldn’t see any other way out. Most of my life, I’ve spent both hating my brother for what he did to my family (and for making it harder for me to do it myself) but also martyring him, even idolizing him for finding a way out and for changing the narrative of his life up until that point.

Tell me, Shel, what’s the meaning of life and death and suicide?

JK.

But serious, though.

You’re a wise man.

Help me sort all this bullshit out so I can get on with my life.

SLC: As expected I have little to share from my heart on these big topics. Death is the supreme mystery, and a terrifying one for me, life was made (if it was made) too fucking hard, also, made or not made, still fucking hard, and suicide is, yes, both an escape from extreme and intense pain and also an act of perfect selfishness. It will devastate the people left behind, of that there’s no doubt. I’m reminded, too, of something guru Keanu Reeves gave as answer to the question, “What do you think happens after we die?” This was during a televised interview and his answered, “I know the people who love us will be sad.” The interviewer simply gave him a fist bump. That is the perfect example of someone who would likely never kill themselves. Reeves thought first of how it would make his loved ones feel. It’s like the exact opposite for those who kill themselves. They figure, I imagine, that, well, I’m not going to be there so what do I care.

I have a couple distinct memories dealing with death in stories. Number one, a teacher once told me you can’t kill a character in a short story. Said there’s not enough space to have the character deal with the death, grow as a person, receive the epiphany, and so on. So I immediately decided to try.

One of my earliest short stories was one in which I killed a young boy. It was called “The Snowman” and written when I was about twelve years old. Writing the story had no profound or lasting impression on me, but the impression and resulting actions by my father in response to reading the story is the beginning of my origin story as a writer. My father read this story and became worried something was wrong with me, a kid who is killing kids in stories. He forced me to throw away all my Stephen King books. He stood beside me while I threw them one by one into the creek beside our house. That motherfucker gave birth to a writer at that moment; if I could make a grown man feel that kind of fear with nothing more than words I wrote on a piece of paper, then what couldn’t I do writing literature? I’ve been trying to bust heads ever since.