I’m not sure I ever put words to this thought, but I’m pretty sure, subconsciously I’ve always known that I didn’t ever want to read a book about San Diego. No shade to San Diego. From my outsider perspective it sounds like a lovely place where some people enjoy their vacations. I have friends who went on their honeymoon there, and though I was very suspicious—as I had never heard of anybody going on a honeymoon to San Diego—they seemed to have a very lovely time.

It’s just that San Diego has never felt like a gritty place for the dark and depressing stories that I am drawn to.

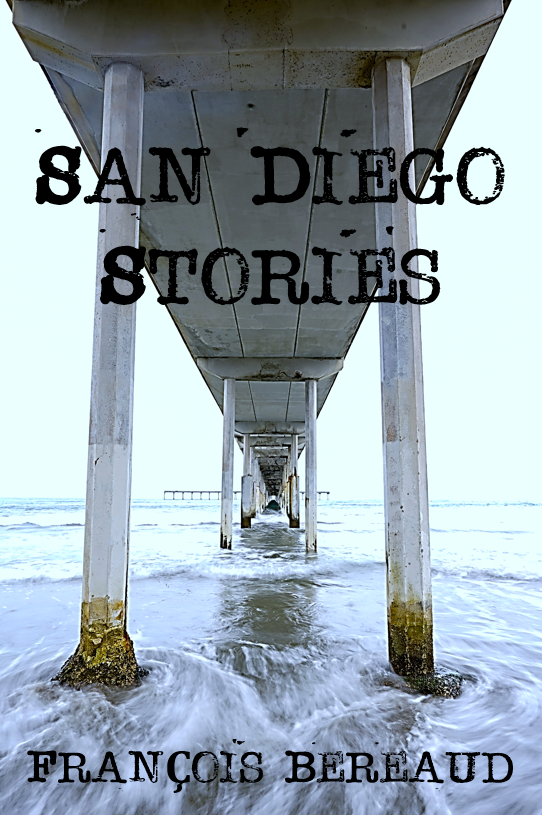

Francois Bereaud has proven me wrong—in spectacular fashion.

San Diego Stories are gritty and ugly and complicated and delightfully weird in a way that I can’t really imagine another writer being able to capture.

Of course, what makes these stories so great are the range of characters that Beraud peoples it with. His ability to write so many different flavors of people with such authenticity is kind of annoyingly brilliant (or at least for me as a kinda one-trick pony writer).

Beyond the characters, though, what makes me even more jealous is Bereaud’s ability to disappear on the page and just let the stories feel like they’re telling themselves. There’s not a line in here where you feel like the author is trying to say, Hey look at me, what a great line is this, don’t you think. There are great lines throughout but you get lulled into thinking these lines just popped into the author’s head—no editing needed, no forced poetry, no patting on the back for what a great simile I just came up with.

There’s some Carver in here, sure. But whereas Carver was clearly always writing characters in his wheelhouse, Bereaud is taking characters far removed from himself. And yet he knows these characters deeply.

There’s that David Foster Wallace, one of my favorites, which encapsulates so much of the understated brilliance of what Bereaud is able to accomplish here:

We all suffer alone in the real world. True empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with their own.

At a time where the world feels very alien and detached from most of our understanding, San Diego Stories are here to remind you of why we need great fiction. It’s the people that we never intended to meet and the places we never wanted to go that we need to learn from the most. It’s how we remind ourselves that the world is still full of people—flawed and weird and different and often irrational and inexplicable, but essentially the same as us where it counts most.

And this why you need to read Bereaud.

[Note here how I refrained from making the obvious pun that Bereaud needs to be read. You’re welcome]

– Drevlow

BD: I feel like we need to get this all cleared up before we can get into the muck. Just how French are you? Like does it bother you that we call French fries French fries? (Tangentially: are you aware that your last name would be BeRead if you took out the U?)

FB: French fries are French fries, what else could they be? (I’m old enough to remember the idiotic “freedom fries” days). I’m pretty French, my Dad was full French so, genetically, half. I’ve lived there about two of my 58 years, but that includes all of first grade and half of ninth grade which were pretty impactful. I speak French, regularly curse in French, keep in touch with cousins there, and, once a month or so, blast the same album by Renaud (the French Dylan in my view) in my car. And I lost my virginity there so there’s that.

BD: Okay, now we’re really gonna get dark and dirty. What’s with San Diego? Can you tell me what a “San Diego Story” is and isn’t? Did you always plan to write a book of San Diego Stories or was it more like, Well, shit, I guess I have a shitload of stories involving San Diego?

BD: Okay, now we’re really gonna get dark and dirty. What’s with San Diego? Can you tell me what a “San Diego Story” is and isn’t? Did you always plan to write a book of San Diego Stories or was it more like, Well, shit, I guess I have a shitload of stories involving San Diego?

FB: It was very much the “Well, shit” approach. I’m a big fan of themed collections and after writing a bunch of these stories, and getting some of them published, it occurred to me that I could put together this collection. The last couple of stories were written after Cowboy Jamboree accepted it and with that aim in mind.

I moved to San Diego in 1999, knowing essentially nothing about the place. I only knew it had a zoo, SeaWorld, and pretty good weather. I’m pretty sure I thought it was tropical and that everyone wore Hawaiian shirts—it’s not, we’re desert chic here. What I knew was true, and continues to be true – though SeaWorld ditched the Shamu bit – but it’s a city so there’s a lot more. One of the first things I did after settling in and starting my teaching job was to volunteer with a beautiful organization called “Mama’s Kitchen.” They delivered daily food bags to folks with AIDS (they still exist 25 years later). I began as a substitute driver with my four-year-old son as a co-pilot. We’d show up and get a neat print out of the route that day. This was pre smartphone and GPS and my son was a terrible reader at the time so it was a challenge finding my way around an unknown city. So many of the dwellings were apartments in alleys or around the back of a larger home with an address like 3745 ¼ . It was a great way to visit different neighborhoods and meet folks with huge challenges. After several months, we got our own route which we kept for five years. The friendships we made were impactful and some of the spirit of the book derives from that experience.

BD: You have a really depressingly natural gift with how to end a story without it feeling like THE END. Or like you’ve worked on THE END for a very long time. Does that come naturally for you? Or is it one of those deals where it’s really hard work to make it seem like it’s easy? Has it evolved for you over the years–your sense of when you feel like a story is done?

FB: I’m sure this question looms over all fiction writers, perhaps most so, in the short story form. There’s always a trigger for me to start a story: something I’ve seen or heard, someone else’s possible story, an image. But after starting, I don’t outline and don’t generally know where I’m going with the characters. I’m sort of traditional with a beginning, middle, end and narrative arc and all that. And I have to put my characters through some shit. I’m not sure how my endings come. I hate to say it’s easy, because it’s not, but I don’t obsess over them, they generally come to me in some form which may be a way of saying I run out of ideas to keep the story going. The one story in this collection where I really changed the end from its first draft is “Intersection.” I think that last line is one of the prettiest in the book.

BD: Along those same lines, I’m in awe of your ability to kind of disappear on the page. I mean that in the best possible way. Your stories feel like they’re just there and they’ve always been there and nobody’s trying convince the reader about what a great writer the writer is. It just always feels like these stories tell themselves and for as many great lines as there are, it always feels like you’ve already killed every darling long ago. Do you have a thing against darlings? Do you enjoy massacring them? Like you’re a serial killer for darlings? Was there a writer who you found yourself reading and you were like, Oh, shit, I don’t have to show off and be a needy narcissistic asshole to be a great writer?

FB: Thank you for the compliment and the question though I’m pretty I don’t really understand it. I’m also pretty sure I’m not a serial killer. I don’t think of myself as an amazing prose stylist in any way. I’ll read other writers and be in awe of the language, not jealous per se, but just “Wow, I could never approach that.” I try to let my characters run around, elude being massacred, and hope that some lyricism falls into a line once in a while.

I never had that thought about another writer but a collection that was quite impactful for me was Dana Johnson’s Break Any Woman Down, a series of linked stories set in LA. Grab that one and you’ll see what I mean.

BD: I love all the spliced stories in here. All the ones where these people’s lives are intersected–sometimes only briefly, largely thematically–up against each other. I always feel like I’m cheating when I write longer stories because the only way I feel like I can write longer stories is to jam a handful of random plots together.

But you actually do this well. Whether there are separate plots weaved together or narrative jumps from porn to monkeys to writing to teachers and prostitutes and run-over dogs and Cavs fans who save drowning kids, well, let’s just say that there’s never a predictable plot turn in here. But it also never feels random either–at least once you seen how they come together.

Do you kind of collect little plot threads or characters and just spin the roulette wheel or is it just more of a “what if” kind of guessing game?

Are there times where you ever get to the end and you’re like, well, I’m not gonna land this one safely?

FB: The opening story which has a spliced plot was actually a homage to a story my grad school advisor, Stephen-Paul Martin, wrote with that kind of structure. I remember being nervous to have him read it, but he was very appreciative of it.

Maybe it’s our stupid cell phone age, but my brain seems to have a hard time staying on track as I get older. I could be playing a hockey game Friday night and think about a math lesson I need to teach on Monday morning, or be teaching that lesson on Monday and have a thought about Thursday dinner. So I guess those jumps mirror what’s going on in my brain. And there are definitely times when I collect a thread and say, “That’s gotta show up in a story.” Now if I were only smart enough to write those down …

BD: Take me through the concluding novella. There are so many threads in there and part I and part II, in different forms. Did you see the map of it when you started? Did you know it was going to be longer? That there would be a part II?

In many ways, this one epitomizes for me bringing all the Francois Bereaud tools to bear.

FB: I feel like I wrote this novella in a bubble. I’m not sure exactly when I wrote it. I never tried to publish any of it until after I had the book contract (a portion of it was published by Blue Press right around when San Diego Stories dropped). When I came across the phrase “Jesus Christ Golden Boy Bail Bonds” (which is explained in the story), I knew that was the title of something. I also knew I wanted a female character who was both anxious—anxiety seems to pervade our lives in so many ways – and also very strong. I had no map or notion of how long it would be. I came up with the conceit of “JustFriends” somehow and liked the idea of telling part of the story through these correspondences. I went down to Golden Boy and chatted with two wonderful folks there to learn about the life of a bail bonds person. I think I had the collection in mind as I was writing it, so, in the second half, I made a deliberate attempt to take the reader on a tour of my city, hopefully in a way consistent with the plot of the story. There are many locations I love which have a cameo in the novella. And the book cover is that pier. Of all the stories in the book, I was most nervous to see this one run loose. What the hell is a novella? And would that weird structure hold anyone’s interest? And so many more worries. A dear friend got and read the book even before I had my author copies. She told me what you said above about the novella being the right closer and, in her view, the strongest work in the collection which meant so much to me. I’m gratified to hear you echo that sentiment.

Ben, thank you for these questions. It’s been a joy. To be a tiny bit of a needy narcissistic asshole, I’ll drop a line from one of the stories which, as I do events, read from the book, and hear people’s reaction to it, I’ve come to see as a tagline for the collection:

Glitzy theme parks and self-promoting slogans aside, the heart of San Diego beats in its alleys.