So here’s the pitch:

Cathy Ulrich writes a series of stories all examining different kinds of plots of different kinds of murdered women (“The Murdered Lover,” “The Murdered Homecoming Queen,” “The Murdered Babysitter,” et al.)

Every story begins with the line “The thing about being the murdered [x] is that you set the plot in motion.”

And we all already know these plots, don’t we? We watch Dateline, 48 Hours, Snapped Notorious: Scott Peterson, all those ripped-from-the-headlines Lifetime movies. I mean there’s even that one podcast that hits the nail a little too much on the head (including the corresponding book).

Obviously we don’t want to admit we watch those shows, or at least we want to/need to qualify that we all feel terrible about watching these shows. But there’s still this: Here we go again, another Friday/Saturday night with Lester Holt and Keith Morrison.

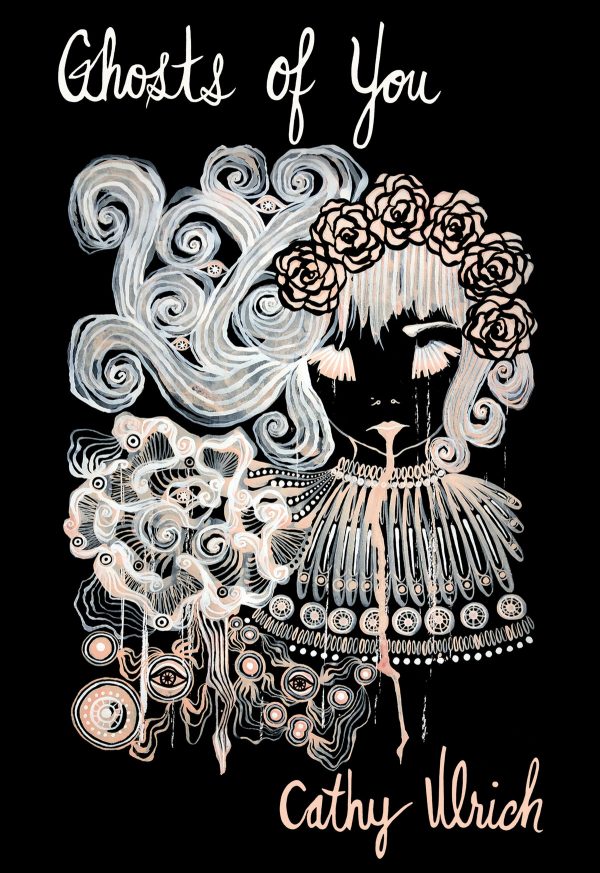

Then comes this collection of short-short stories from Cathy Ulrich that should be required reading for us, except it’s also not at all like any of those shows. It’s the complete opposite, actually. But it’s not a scolding kind of book. That would be too easy, too expected. It’s not a parody, not even a satire of the type of people who make these shows and watch these shows, which is to say, people like us.

First of all: Ghosts isn’t a murder mystery. In some ways, it’s not even about the murdered women that we have come to fetishize in disturbing ways. It’s about the absence of the murdered women. It’s about the story of the murdered women that always gets hijacked by the murderer. Everything that gets left out of the narratives that get written about each murdered woman who usually gets lost in the story.

For example: all the family and friends and random acquaintances and complete strangers the murdered women leave behind, the stories they tell themselves later, the questions they ask, those weird, messed up thoughts you find yourself thinking and not wanting to think in the aftermath of tragedy.

It’s about the way Cathy Ulrich negotiates a line, a paragraph, the way she takes all these stories and makes each one surprise and linger no matter how many times you read, “The thing about being the murdered [x] is that you set the plot in motion.”

Of course that’s the whole point. Over and over, setting the plot in motion. The way Ulrich always manages to twist the “plot” with some new wrinkle that simultaneously seems so true and obvious but also unexpected but of course also… obviously… expected.

It’s book you weren’t expecting but needed to read, what you all need to read if you haven’t already.

It’s about the force of nature that is Cathy Ulrich and all that she brings to the page and all she leaves out.

And if you need further evidence, here are some of the smart and very human things she told me along the way.

BD: I was wondering what “set this plot in motion” for you?

CU: I’ve mentioned it in previous interviews, but the first story in this collection was really sparked by reading a story about a murdered girl in a small town and how it affected the community and, oh, I wish I could remember who wrote it and where I read it, but it’s been probably five, six years ago! But it got me really thinking about how a lot of fiction removes any agency from the victim so we, the readers, can just enjoy the hunt for “whoddunit,” you know? Which makes perfect sense—once you are dead, what agency have you got? But at the same time, a lot of these stories/movies/TV shows seem to forget that the victim was ever anything but a puzzle needing a solution. And that got me really thinking. I’d read about “fridging,” which was kind of coined by comic writer Gail Simone, who kept track of women murdered as plot points in comic books on her website “Women in Refrigerators.” All these women murdered in the purpose of furthering the plot, usually for a male character. They have no power of their own, no story. They are only ever there to “set the plot in motion.”

So with all that rumbling around in my head, I wrote “Being the Murdered Girl.” And then I was done!

Except then I learned about Joan Vollmer, who was shot to death by her husband (you’ve probably heard of him) William S. Burroughs. I had never heard of her before. But I’d heard of him. Her story got lost in his fame—and he was the one who killed her (whether it was accidental, as he claimed, or no). So I wrote “Being the Murdered Wife.”

And then things kind of snowballed and I ended up with Ghosts of You.

BD: I was really fascinated with the way you work with the second-person point of view here. Most of the second-person I’ve read tends to be the Lorrie Moore Self-Help second-person where it reads a bit like first-person but the narrator talking to themselves (which as someone who talks to themself a lot, I dig).

Then there’s more of the epistolary second-person where it’s either directly addressing someone or it’s more of the voice of the storyteller and letting all us readers gather round (which as someone who is constantly having arguments in his head, I also very much dig).

In Ghosts of You, there’s almost an omniscience to the second person here. On one hand it makes perfect sense based on the title of book that at least in some sense these stories are presided over by the ghosts of the murdered women.

On the other hand, with the omniscience of the second-person here it almost removes the murdered women from the story and instead focuses on the absence of them in the aftermath. These are not the really the stories of what led up to the murder; these are the stories of how the families, the friends, the neighbors, etc. respond to the absence of these women.

So I guess what I’m getting at is this:

How did this point of view evolve for you? Was it something that sprung forth naturally and you just went where the lines took you? Or was it something more intentional where you knew what you were doing from the start?

CU: I’m very comfortable working in second person. I’ve noticed that, a lot of the time, when I think about myself to myself, I’m referring to myself in second person. I’m not sure when I started doing this, or why, but it’s led to a lot of my stories being written from the second person point of view as well.

For me, I “hear” the voice of a story before I write it—usually the first sentence pops into my head. I’ve found that if I mess around with the way I’ve “heard” the story, changing tense or perspective, the story goes flat and I have to throw it out. So I’ve learned to leave my stories be!

In this case, you’re exactly right, though. I’m not sure these stories are written in a true second person voice—it seems like someone is addressing them, an omniscient narrator who knows everything that even the title character doesn’t know, and can’t know.

So, to answer your question, it was definitely something that sprung forth naturally. I wasn’t trying to write from this perspective. It was the perspective that chose me.

BD: It would seem to me that a great challenge of putting together this book would be how to select stories and organize them in a way that allows readers to jump around from story to story, but also appeal to the readers who want to go cover to cover.

Of course, that’s a challenge in putting together any collection, especially a collection of flash fiction, but in this case we both need the serialization of the premise, but we also want to feel as if each story is putting a new spin on the previous story, while at the same time building to something larger by the end.

What was that process like for you? How did you decide what to put in and what to leave out? First vs. last? And what about the editing? How did you make the call on what was repetitive vs. what needed to be threaded through from one story to the other?

(That’s a lot of question. Sorry. Honestly, I’m actually pretty terrible at these interview’y things I keep trying to do.)

CU: As far as putting the book together, I was very lucky! The stories kind of evolved as I wrote them. So with the exception of a couple of moves for similarity (for instance, “Being the Murdered Student” and “Being the Murdered Daughter” both really look at a family dealing with the immediate aftermath of the murder) and the exception of insisting the collection end with one of my favorite pieces, the stories are placed in the order they were written. So the readers are really seeing how these stories have grown and how I have grown as I’ve written them. That said, I think if you jump around from piece to piece in this collection, it won’t hurt your experience any—unlike some of my other series, there’s not a narrative arc that they have to follow, so readers are more than welcome to read these stories in any order they’d like!

One of my favorite things is when people tell me, “this was the best one,” or “this was my favorite,” because there are different favorites for different people, and that makes me so glad. I hope that everyone who reads these stories can get something out of them.

BD: I was wondering if you might talk about your affinity for paired stories and series of stories (a la your Murdered Lady stories, Japan stories, Astronaut Love stories, et al)

I read in one of your interviews that you have already written another handful of “Murdered Lady” stories. It seems like a lot of your writing is instinctual—allowing the voice(s) to take the story where it wants to go.

Are you the type of writer who gets caught in loops/cycles of thoughts? Is this where the serialization comes from? Or is it more just following different threads to their natural conclusion?

As someone who has both OCD and ADHD, I love the way Ghosts bounces around on all these threads where it’s both recursive and stream of conscious’y hopping from thought stream to thought stream.

Is this similar to the way your brain works or am I trying too hard to project my inadequacies onto you?

CU: I think my writing is very instinctual—I definitely find I lose the “story” if I sit and think about what I want to do and how I want to do it. I need to just sit down and let the words carry to their destination. I can clean up little things on editing, but, again, if I make any big changes, I usually lose the story.

As far as writing all these connected pieces, these series, I think I’m drawn to them because they allow me to look at one thing from various viewpoints.

Take the Murdered Ladies series: These stories are all basically about the aftermath of a murder. But by telling the same story from different perspectives, I’m able to look at it in different ways. I find that interesting. The Japan series is kind of the opposite. It’s the same character, but in different situations. So I’m able to focus on developing this character, but from a whole bunch of different angles.

Now as far as how my mind processes all this—whoo, boy! That’s a tough one. I remember when I was a kid, they had an adult come to our school and pull me out of class to ask me questions. I can’t remember if they did this with all the kids (I kind of hope so, but I also kind of think it might have been just me because I was a first grader reading at a high school level, thus making me incredibly popular and definitely not picked on at all), and I can’t remember what they asked me exactly, but I told them that I sometimes heard this little voice in my head, and until they were like, “okay, yeah,” I had no idea that was thinking. And the point of this little anecdote is: I still hear a little voice in my head and it’s probably thinking, but who knows what my mind is up to! It’s weird in there!

BD: One of the things I appreciate most about this collection is the humanity that exudes from every story. It’s not reductive; there aren’t cheap shots for the sake of satire or parody. Often we think of “political” writing as scathing satires or diatribes. This is exactly the opposite. For me, it’s a much more powerful political statement—the refusal to reduce these characters’ lives/suffering into a punchline/zinger/burn.

In a weird way, it reminded me of the best work of George Saunders, the way that a lot of his characters start off seeming to be these absurd caricatures but then become much more complicated in their flaws and motivations by the end, not necessarily to rationalize their bad acts, but to get at a much more complicated truth about humans—”good” and “bad.”

With this topic especially it can be so gross, when you step back and look at the way women are used not just in fiction, but in the news. And then to think about why this is such a depressingly common news story in the first place—the murdered woman—I imagine it would’ve been easy to write these stories from a much different tone and point of view.

Was that something that you were thinking about has you were approaching this project (not the Saunders thing, but just the approach in general)?

CU: For me, for all my stories, it is about finding humanity in the characters. I’ve even had characters in these stories that I know I wouldn’t like in real life (for example, the mother in “Being the Murdered Coed,” I don’t think I would like her at all!), but in the story, I am letting them be themselves. I am letting them be heard. I don’t want anyone in my stories to be a joke or a punchline—that wouldn’t be fair to the person they are. I wrote some of these stories when I was very angry (“Being the Murdered Mama,” “Being the Murdered Indian,” I wrote both of those right learning about another victim), but if I wrote my anger into the story, it would be just a rant or a diatribe. And that’s not what I want at all. I want real people, doing the best they can. For me, that’s really the heart of all writing, whether it be fiction, poetry or creative nonfiction.

BD: In your final story, “Being the Murdered Indian,” you delve into another depressing component about the way our culture fetishizes dead woman narratives: race, or more accurately, “whiteness.” Racism in the way we report the news is no real surprise, but racism in the way we report true crime is something that seems to have become so suddenly ubiquitous in not just in our news but in our pop culture: the idea that we will care more about the dead based on how “pretty”/”white” they are.

I think most of us are at least somewhat aware of the research they’ve done on the biases between “whiteness” with perceived “beauty,” but especially in the age of Dateline and 48 Hours and all the adjacent shows on ID network and Oxygen (even on our podcasts), this bias toward “pretty dead white girl” feels like it’s actually getting more ingrained in our culture (i.e. if the victim isn’t white and/or “photogenic,” viewers will turn the channel to a more sensationalized story).

In another story from the book “Being the Murdered Blonde,” you write, “The girls will look in their mirrors, in their reflective screens, dream of seeing your face there instead of their own…. How you were bone-China thin, how the coroner must have held your hand like you were a living thing, how, they will dream, he wept. / Their parents will say: Such a pretty girl.”

I mean there’s so much societal shittiness to unpack when examining the “pretty dead white girl” narrative on so many different levels here (and we haven’t even touched on the hetero-normativity). And in this case it’s all premised on the issue of reportage and representation: is it better to have more news coverage of dead women to bring light to the huge problem with have with violence toward women? Or would it be better to have less reportage of dead women so that we would stop fetishizing this story of dead women?

And all the same could be said for dead people of color, except maybe the opposite. Would it be better to have more stories about women of color who have been murdered (and whose stories have often gone over looked)? Or…?

Honestly, Cathy, I’m struggling to find the right question here. Maybe that’s what I’m asking you: Do you have the right question?

CU: I am part Chippewa Cree and part black (and half white on my birth father’s side), but I was adopted and raised by a white family. I know that this gives me an advantage—I keep thinking, if I went missing, if I were murdered, because I have been raised with the advantages of passing as white, the authorities would probably be less dismissive of my case than, say, someone like Misty Upham, a Blackfeet actress who went missing (and then died) and probably could have been saved if the authorities had taken her and her family seriously.

The fetishization of the “murdered girl” is something that really bothers me. I mean, look at Elizabeth Short! How many people know who I mean when I say her name? But if I say “Black Dahlia,” everyone knows. She was made into this thing to sell papers. No one really knows Elizabeth Short. But everyone knows the Black Dahlia.

And, yes, being a pretty girl, being a white girl gets you more attention as a murdered woman. It maybe gets your murderer found. It maybe doesn’t. It makes you famous. But what does it matter to you?

So the way these cases are often portrayed in the media, yes, that bothers me a lot. But I see reporters trying to do good work out there. One of my stories, “Being the Murdered Clerk,” is based on a local murder. This girl felt real to us all because of the hard work that the reporters who kept track of her story put into keeping her “alive.” The reporter in the story is based on a real woman I worked with at the newspaper. She kept copies of the reward posters. She checked in on the girl’s family. It wasn’t just an article to her. And that is so powerful. She’s not a reporter anymore, but I hope she saw, like I did, that this summer, they finally caught the man who murdered this girl. That finally her parents have an answer. It’s a bad answer—there’s no good answer for “why did someone murder someone I love?”—but it’s an answer.

So in my stories, I tried to avoid the sensational and stick with the humanity. I wanted all these girls, these women, these ladies to be real. Some of them are gay. Some are bisexual. Some are white, some are black, some are Northern Cheyenne. Some are mixed race like me. But I didn’t want the what they were to be their story. I wanted their story to be who they were, and what was left behind.