Santiago de Compostela, Spain

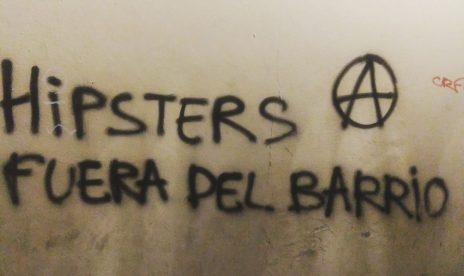

There is a café here in Santiago called Avante! frequented principally by students and post-grads, whose walls are near-to-exclusively covered in Leftist memorabilia. I have overheard some Americans—most recently a group of Patagonia-clad boys from Colorado—excitedly call it “the communist bar” as if perhaps the First International were meeting down in the storeroom. The décor of the place is a catholic assortment of revolutionary bric-brac, a tintype of Lenin looking sternly determined, hammers and sickles distributed with haphazard liberality, a poster that declaims GALICIA FOR FIDEL (Castro’s father was born in a small town close to Ourense) AGAINST THE BLOCKADE, there is quite a lot of dancing to muñeiras (Gallegos are emphatic about their Celtic roots and some of their music resembles Irish or Scottish music) the lower floor is covered in broken glass from smashed bottles. Bella Ciao is frequently played, as well as Entre Poetas y Presos (Between Poets and Prisoners). There is the occasional lacuna in the revelry whenever the owner hijacks the loudspeakers to play The Internationale which is rather a hard song to dance along with.

The owner “has been to jail a couple of times” a coworker, Xacobe, confides.

“Not for anything political, petty crimes.” he waves a hand “He’s kind of an idiot. It’s like, Galician Nationalism isn’t E.T.A.” (the Basque terrorist organization which declared a formal ceasefire with the government in the 2000s) “We’re not setting off bombs in the street. But he thinks we are.” He laughs.

The school where I work is situated just outside Santiago de Compostela, in a rural concello called Touro whose name derives from the Galician word for bull. Galicia is the most northwestern province in Spain, nestled between the East Atlantic on one side and Northern Portugal on the other. The Galician language predates Iberian Portuguese by some centuries, while sharing a lot of the same morphologies and superficial characteristics. Despite this relatively well-documented fact pattern, the linguistic debate over Gallego remains fraught. It wasn’t until the 70s that the linguist Ricardo Carvalho coined the term reintegrationism referring to the theory that Portuguese and Gallego, far from being linguistic isolates or distant cousins, are each variants of the same tongue, born in Douro valley, straddling the Portuguese-Spanish border—The Stripe as it is colloquially known. The Stripe is the oldest continuously operating boundary in Europe. Save for some small brinksmanship on the part of a Corsican-French corporal in the early 19th century, it has for the most part been peaceably maintained. Carvalho—a Leftist intellectual with Galician Nationalist sympathies—split a good deal of his academic career between the lecture hall and a prison cell (the Galician language, like Basque, or Catalan, was banned under Franco’s regime) and wasn’t permitted to hold any academic office of public trust until 1970 or so. In the decades since the pivot to democracy, ordinary Galicians have done the slow, hard work of trying to claw their language back from the brink. A generation ago, parents had a terror of teaching their children Gallego—for fear that if they were caught speaking it, they’d be unable to advance in Spanish society. Now, Gallego grammar is taught in some schools (mine, for instance). The language looks, slowly, if not surely, to be making a comeback.

Santiago de Compostela and the surrounding concellos are a hotbed Galician Nationalism, certainly more than larger cities like Vigo or A Coruna.

“You could spend a week in Coruna” an acquaintance told me “and never hear a word of Gallego.”

It’s quite easy to recoil at the phrase “Galician Nationalism” as an expression of some illiberal or reactionary stripe, but it is worth exploring the context here. In the stultifying racial politics of 1970s America, Kwame Ture and the Black Nationalist movement were at times the sole vocal counterbalance to the neoliberal consensus of the Watergate Babies, and Nixon Republicans’ pathological race-baiting. They were out in the streets, on television, promoting Black Pride while everyone else was either dead or quiet. This is not necessarily to compare the Galician Nationalists’ situation to that of the Black Panther Party in the 70s and 80s U.S., but in the Fascist decades following Franco’s conquest over the republicans, the Partido Galeguista here—and Basque Nationalism farther to the east—signified some vestigial resistance, some sense that while the Francoists had cut down all the flowers, they could not by sheer force of will stop the Spring.

Even today, the Partido Galeguista plays the part of loyal opposition to the conservative stranglehold on the regional government. It is the second most popular political party in the region.

Touro is maniacally green (Galicia has got a microclimate similar to the Pacific Northwest of the United States) it benefits from around 230 days of rain per year, and is ringed concentrically by acres of eucalyptus. The species is obviously not endemic to the region, and my coworkers almost uniformly view them as a blight.

“In the 90s here, the Spanish government decided they wanted to turn Galicia into a logging sector. Great! So what did they do? Eucalyptus grows incredibly fast, doesn’t need much water, and the trees produce good lumber.” My school’s science teacher explained. “The problem is: it’s an invasive species. It decimates the soil, robs other trees of their nutrients. These oaks here” he gestures “they were, we think, planted by the Romans when they invaded. So, it is not like they are completely endemic either but the eucalyptus, they are an ecological disaster.”

This is rather illustrative of how some Galicians see their situation in general. Their language banned, their lands appropriated by the fascists, then in the hurried pivot to a modern European economy, their farms and forests got bought up lock stock and barrel, exploited to the hilt, ravaged by private investment. The Romans brought the vulgar Celts to heel and then planted their red oaks, and some 2200 years later, the logging companies came in and planted their eucalyptus. During no intervening period was self-determination realistically discussed.

Touro as it happens is located smack dab on top of a brownfield copper mine. From 1973 to 1986 the open cast mining operation here was in full swing, lucrative ore was being extracted at a furious clip, some very smart businesspeople grew quite wealthy overnight. It was only when a couple of citizens noticed that the water in their taps had begun running bright orange that the local government pumped the brakes and, following some public health investigations, shut the mine down.

The copper mine, now, has been converted by people who know better into a waste treatment plant. You can tell when one of the trucks from the plant is travelling through town. The odor spreads up and down the street til it befouls everything. It is an acrid sulfuric scent. Fran, the science teacher, earlier here quoted, took some of the school’s older students recently to tour the concello on foot, to view the extent of the environmental damage, and allowed me to accompany them.

“Note the smell” he said dryly, pulling down his mask, as we passed along an access road abutting a handful of small farms “The neighbors here say it flares up from time to time, comes through their windows. They get nauseous, cannot eat.” He jumped up and down on the dirt underfoot. It had not rained recently in Touro, but liquid pooled in divets along the trail. “Sometimes, like now, the waste seeps up through the ground.” He instructed his students. “Imagine living here.”

There’s a fight now in the offing, about reopening the copper mine. It was closed without all the ore having been extracted, and historical memories—particularly those of local political leaders—can be opportunistically foreshortened.

The mine was bought up recently, by a company that some of my coworkers have described as “an Alaskan multinational” though all my cursory research could yield was a 2012 purchase-option announcement from a base metals extraction company called Lundin Mining in Canada, and a handful of recent public press releases from Atalaya, a Cypriot mineral extraction outfit, saying that they had acquired all the necessary rights to move forward on Proyecto Touro, as well as one statement from the CEO of Atalaya defending the project from public recriminations, following a rather jaundiced Environmental Impact Assessment.

Proyecto Touro has been designed with a fully lined tailings storage facility, constructed downstream using compacted rocks and with a guaranteed zero discharge policy following international standards and best practice. We are very surprised by the public statements made by the representative of the Environmental Department...

We will continue to explore all possible avenues to develop the Proyecto Touro and shall build on the excellent work performed by a very large team of world class specialists.

All along the main drag of Touro are hung signs that read

MINA SI! EN TOURO – O PINO (Yes to the mine, in Touro and O Pino!)

Or

NON AO TERRORISMO MEDIOAMBIENTAL (No to environmental terrorism!)

Or

CHEIROS TEN NON

Cheiros is the Gallego word for a foul odor.

The field trip passed over a meander of the town’s small river, the Ulla.

“Stop.” Fran the science teacher called out. The group of students all halted and stared down toward the riverbed. The banks and floor of the Ulla are painted bright orange from chemical runoff.

I asked the school’s art teacher Xacobe whether this was from the copper mine or the waste treatment plant. Xacobe is a rather scruffy folk musician with hair that hangs below his ears and an earring in one lobe. He is thin like he needs feeding, high-spirited and gently radical in disposition. It was he who told me all about the owner of Avante, and the eucalyptus problem, and the business with the mine here.

It is difficult to imagine that a mine closed in 1986 could have contaminated the river for the following four decades. That the knock-on effects from corporate negligence could have such a long tail. But it is also difficult to imagine that a waste treatment facility would be able to pollute a river so visibly without public remunerations or significant consequences. So where does that leave us?

“The thing is, it is difficult to know.” he said. “You can tell it’s polluted but can you prove it was this company versus that company?” he smiled. “It’s very difficult.”

I asked Xacobe when they will hold the vote on the copper mine, when this debate will all finally come to a head.

“The thing is” he said “they don’t ever need to formally vote. The alcalde, the mayor, he is in-favor already. Everything else can happen without anyone voting. Agreements between private companies.”

Why do some people support the mine?

“They think it will bring back jobs.” He says. “What they don’t realize is that even if it does create jobs, they’re not going to employ anyone from Touro. They’re going to bring in specialists from outside Galicia. From Madrid or wherever.”

It was perhaps during this ride, or the one previous, that Xacobe broached the idea of cutting down a eucalyptus to me, “A small one I mean.” He said. “The kids need it for their art project.”

The school kids in Touro are making and decorating one of those large directional signs, the kinds that tell you how many kilometers you are standing from Bangkok, or Sao Paolo, or the Straits of Magellan. It is a fun project and the students all seem very excited about decorating their signs, looking up the exact longitudinal coordinates of the United Arab Emirates, etc.

“But we still need the signpost.” Xacobe explained.

“It isn’t technically illegal.” He assured me. “Because the loggers are supposed to leave a gap of 15 meters between the eucalyptus they plant and the road shoulder. They’re supposed to, but they never do, and no one from the government ever enforces the law.”

A waste truck rolled by and the air grew ugly for a few minutes.

“I already have a saw in the trunk.” He added. “We just have to arrange a day.”

So it was, on a cold recent morning, that I met the art teacher Xacobe before the sun began to rise outside his apartment in Santiago de Compostela, and we both piled into his beaten-up blue Citroen and set out in the dark for Touro. Once we exited the highway Xacobe pulled the car off onto one of the dirt logging roads that honeycomb the town’s outskirts, and left the engine idling as we got out blowing into balled fists and surveying the forest. I stood shivering while Xacobe assayed a couple of small eucalyptus on an embankment, selected one about five inches in diameter and fetched the two-handed saw from his car’s trunk.

The tree wasn’t very big, but the cold and the meager light made it into slow work. We kept being interrupted by passing lumber trucks and having to dash off into the forest with the saw in hand to avoid being see even though Xacobe kept insisting that what we were doing was technically legal. In all, the project took about 15 or 20 minutes crouched low in dead bramble, working the saw together in the dark.

The tree came down with a protest and a crash, laying orthogonal to the dirt road. It was perhaps three meters in length, and we scrambled to cut it down to size, and hoist it into the back of Xacobe’s car. We arrived to school before anyone else, and carried the eucalyptus inside like two jolly pallbearers. We left it in his classroom and then went back out to have a coffee.

On our drive back from town we saw an old Galician man walking the shoulder of the highway beside a length of postholed farm fencing. Some local agitant had strung anti-mining posters on every fencepost for more than a mile going. The old man—whether because he was being paid by the mining outfit, or because it was his property and he is a particularly dedicated member of the MINA SI contingent—made his way slowly along the fenceline, tearing down all the posters one by one. The hills were green and filled with cows. Through the rolled-up car windows his labor appeared silent, as if it were happening on a planet without any atmosphere. The fence posts might have gone on forever but the old man seemed in no hurry to finish his work.