Barry Hannah died the other day. Tim told me this morning, but I guess by then it was old news via the Internet, and I felt kind of bad about that—being so late on knowing—because I was cooking dinner or brushing my teeth or sleeping. But you’ve got to do those things, and you’ve got to die, too.

Barry Hannah died. But it’s okay, because it has to be.

And I suppose this post about Barry has to be, because I can’t seem to do anything else until it is. But it won’t be poetic, or well-thought-out, or the melodious dirge I’d like it to be, because hopefully it’ll just pour.

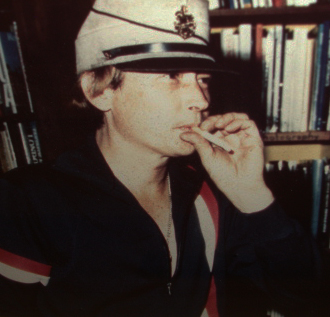

Two or three summers ago, after some long years of reading and admiring him, I got to hang out with Barry for a week in Massachusetts, a state in which we both didn’t seem to know what to do with ourselves. The social nexus was some kind of old house/inn, and the nexus of that was an outdoor courtyard thing, where Barry would sit amongst us admirers and ask around for a light for his long, generic cigarettes.

Upstairs in a creaky wooden room with a few others we all talked about our stories. He read one of mine, and bled on it, because he was wearing a lot of Band-aids about this time. I suppose there could be some kind of grandeloquence to be made about Barry bleeding on a manuscript, but it was actually kind of gross. An agreeable grossness. The blood was brown and smeared.

The story, he said, needed a greater sense of menace. It was one word that changed everything.

One day he came into that room rather dejected and said his editor had phoned to tell him she’d read his latest stuff and could not make a lick of sense out of it. He’d been on medication when writing. He was sad about it. And despite his overall literary eminence, he made a long point of commiserating with us pale, crappy writers about the cruelty of it all. “You’re always a happy amateur,” he said, “as long as you can stay happy.”

I like that one.

It seemed Barry and I shared a guilty habit of walking out on large auditorium readings when the reader did only that—read—just read the words they’d written real fucking nicely on a piece of paper. It’s pretty easy to tell whether someone is just stroking themself behind a podium instead of trying to tell you something.

I found Barry in the empty lobby outside the hall and he asked if I could take him back to his motel. In the car he said he didn’t much care for poetry, the new stuff. He said he’d rather be watching TV, Comedy Central, he liked that channel. In the parking lot he opened the door and said “Bye-bye,” which I remember thinking people don’t say much anymore.

This all may seem to make Barry out to be just a guy, but he was just a guy, a real fucking great guy like others out there that make you happy and proud to be around and every now and then something comes out of their mouth that makes you realize that your life and this world you live in is really something amazing.

And his writing is made up of these things 100 percent. People talk a lot about his sentences, and it’s all true. Every one of them aims to tell you something, and inside that telling there is always something amazing.

It’s very sad to see him go. But it’s a very generous thing that he was ever here at all, that he wrote what he did, and that he left so much of himself behind on those pages.