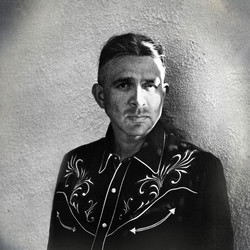

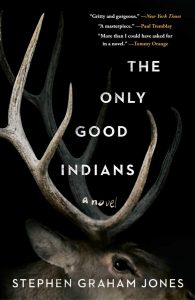

Stephen Graham Jones writes about cars, trucks, cowboys, Indians, slashers, zombies, and werewolves as fluently and fondly as your grandma talks about the intricacies of each of her grandchildren. If you haven’t read his work yet, you’re in luck: The Only Good Indians (Saga Press $26.99) was released last month, and his next book is due out in September. Atop that, there are twenty-five other books of his out in the world available for purchase.

DT: The Only Good Indians very much falls off the page like Hemingway with a haunting (to boil it down for all readers without spoiling the story). After writing two dozen or so books, how did you arrive at haunted people over haunted houses, and personified karma over a supernatural monster for The Only good Indians?

DT: The Only Good Indians very much falls off the page like Hemingway with a haunting (to boil it down for all readers without spoiling the story). After writing two dozen or so books, how did you arrive at haunted people over haunted houses, and personified karma over a supernatural monster for The Only good Indians?

SGJ: My love for the slasher, man. I realized, after Mongrels, that a big part of what made it work was that werewolves are so close to my heart. And, slashers are just as close. Before The Only Good Indians, I’d done two slasher novels, I guess—Demon Theory, The Last Final Girl—but I hadn’t said even close to all I wanted to say in and with and around the slasher. So, I committed to the slasher. I wrote this one, then another, and another. But I also wrote a haunted house novel. Oh, and a slasher novella, I guess. And I guess a ghost novella. I just love all the parts of horror, but the slasher, the slasher’s really special for me. I like the sense of justice in it. I like how bad deeds are punished. That’s not the world we live in, but, while reading a slasher, we can pretend for a little bit…

DT: How has COVID changed your writing regimen, prolific as you are, now that leaving the house and office is largely voluntary? How is writing during a plague for an author primarily known for horror?

SGJ: Mostly what it’s meant is that my hands hurt a lot less. In the before-times, I did so much writing on airplanes and in airports and at bus stops and in hotels and hotel lobbies, and just lobbies everywhere. I’m kind of a professional lobby writer, maybe—not coffee shops, though. I can’t really handle the smell of coffee very well. But, hands: all that writing-while-travelling means laptop work, which means a cramped little keyboard instead of my handy-dandy Kinesis Advantage 2, where I can type so fast and so naturally that it feels like telepathy to the screen, really. The reason laptop keyboard hurt my hand, singular I guess, is that I’ve broken my right hand… either four or five times, it’s hard to remember. Kind of made a career out of it for a while. So the bones in there are all jacked, and from sports, I’ve also got some fried tendons in my fingers. Meaning, man, give me my good keyboard and I can cook. I can also cook on a laptop, on the road, but I have to pay for that. All of which is to say that writing, these last few months, during the pandemic, it hasn’t hurt as much. Physically. But, too, what am I saying? It’s always grueling emotionally and intellectually and probably even socially, but that’s not pain, that’s even trade. Having to wrap my hand in tape to use a spoon, though, and having to brush my hair with my left hand, that’s a different kind of trade.

DT: When I think of West Texas—where you grew up and spent a good bit of your life—I think about mule deer and pronghorn antelope. How much of the elk hunting came from experience, and how much came from research specific for the book?

SGJ: In the West Texas I grew up in, man, I bet I saw maybe four deer, my first eighteen years? Probably less. They weren’t around. And, I was always out in the pastures, skulking the draws with a rifle, or on a horse, and I was always out early moving irrigation line too, where I’d see mountain lion prints, lots of coyotes, plenty of snakes—snakes all day long—but, deer . . . not so much. There were probably mulies around that I was missing, as they were smart enough to avoid me. And, I hear that, since I’ve left, the deer have moved into West Texas in real numbers, enough to actually hunt. Which is crazy to me. Never any pronghorn, though. Have to go about three, four hours north of Midland to start running into antelope. As for elk, I grew up hunting them. Dressed my first one out at twelve, I guess, and still have a scar on my hand from it. And I’ve mostly only hunted elk on the reservation. Only a couple of times here in Colorado.

DT: I read that Jonathan Thunder’s (a Red Lake Ojibwe artist) sketch on the cover of Deer Woman: An Anthology inspired some of the visuals in The Only Good Indians. Did you take a measured approach when mixing contemporary Native elements with traditional Blackfeet beliefs in this book, or did you allow the story to evolve on its own? The book seems underpinned with balance righting itself, no matter how horrible the outcome.

SGJ: Yeah, good call, being a slasher, righting itself has to be what it’s about. And, yeah, that beautiful art on Beth’s book has to be part of The Only Good Indians, as that was right here by my keyboard for a long time. As for the deer-woman stories, though, gotta say, aside from that Deer Woman vignette, the only one I knew going into writing this was probably John Landis’s, from Masters of Horror. If they’re Blackfeet, anyway, I don’t know any of those stories.

DT: Your book, Not for Nothing (Dzanc Books $15.95), and The Bird is Gone (FC2 $19.95) will always be your most compelling reads for me. What book(s) of yours would you suggest a new reader pick up after The Only Good Indians?

SGJ: Probably either Mapping the Interior, as there’s a person from it in The Only Good Indians, or, for slasher wackiness, Night of the Mannequins. For werewolves, though, man, there’s Mongrels. My heart’s buried in that book. But, too, I bury my heart in all of them, of course. Can’t seem to help but.

DT: What other writers should fans of your work look forward to in the coming months?

SGJ: You, your memoir, maybe? As You Were—can I say you? And Toni Jensen’s new one, too, Carry. And Rebecca Roanhorse’s Black Sun.

DT: Is there anything that reviewers and interviewers are getting wrong or missing completely from your intentions when you wrote this book?

SGJ: I’ve done a few events with Percival Everett, and he always has readers come up after, pitch their read of this or that of his to him, then end with a question mark— “Is that right?” Everett’s answer is always a grin and nod, that, yes, that’s right. And also, the other read it right. They’re all right. I take him as my model—for this and for everything, pretty much. But, especially for this. I don’t think there’s any wrong takes. If you read it, then whatever you say’s right. And, talking role models as I seem to be, I should also say that, on a panel with Joe R. Lansdale in 2001 or so, in Austin, Texas, an audience member asked him what genre he wrote in? His answer is that he writes in the “Joe R. Lansdale genre.” I aspire to that.

DT: Thank you for your time, Dr. Jones.