1

When you’re asked to officiate a wedding, first consider who’s asking, and why. You only know the couple through your partner, and because she went to them for support during your summer-long separation, they must already know you’re not the ideal candidate to stand in front of large crowds and talk about commitment. When they say they want you to write the ceremony because they respect you, because they believe you’re talented, accept the compliment. But consider that you may not have been their first choice. Consider that they may have been desperate.

2

Actually, you have very little understanding of what they’re asking you to do. You grew up Catholic, which meant wooden kneelers, chalky wafers, creaky old voices warbling up to the rafters. Stuffy, guilt-drenched sermons, priests droning hymns. Weddings meant all this, too, but with rings at the end. Picture yourself in a black-and-white robe with a detachable collar. Fifteen minutes, the couple tells you. Completely secular. No blessing, no unity candle, no calling the parishioners up for communion. This, of course, is what you want to hear. And yet, a small part of you liked imagining the spectacle.

3

Don’t say yes because you find the couple inspiring, or because you value their friendship, or even because you want to make your partner proud. Say yes because it may benefit you. You know this is selfish, but you’re no stranger to selfishness—the cause of so many silenced phone calls, lost friendships, your summer-long separation. Selfishness and guilt: these two feelings have come to define you. Say yes, too, because there may be something redemptive about the experience. Because you think that it, like everything else you say yes to, might somehow make you better.

4

The first step in officiating a wedding is to ignore it for a month. Every few days, think of it with a shudder and let it drift away. This always happens: the idea of the thing is appealing until it approaches and its reality leaves you paralyzed, excitement turns to dread. When your partner asks you about your progress, shrug and make noncommittal noises. Tell her you’ve been thinking about it. Say, Only fifteen minutes. Wonder if the couple might have someone else in mind, if there’s still enough time for a replacement to relieve you of your duties.

5

The second step in officiating a wedding is to watch Youtube videos. Lots of them. Note that none of the Internet-ordained officiants are completely secular, even when their video’s title labels them as such. They all slip, often just for a word: “blessing” or “spirit” or “faith.” Worry that a phrase from your Catholic upbringing might slip mid-sermon, the muscle memory of the Apostles’ Creed. Try to pinpoint the moment you lost faith and realize that this, of course, is impossible. The loss happened over time, both naturally and surprisingly, like the word “eternity” from the officiant who just wants his friends to be happy for the rest of their lives.

6

You expect there to be a test, or something. Instead, you type your name and address into a form and pay forty dollars to register as a minister in the state of Michigan through a non-denominational, San Diego-based church called the Open Ministry. It’s easier than signing up for a mailing list, and certainly easier than removing yourself from one. In a few days, you’ll be sent a certificate to pass along to the couple, who will show it to the Saginaw County Clerk to prove they’re in capable hands. After you register, browse the Open Ministry website for tips on writing a secular ceremony. With four months until the wedding, remind yourself that you have plenty of time, that you work best under pressure, even though you’ve tested this theory enough times to know it’s not true.

7

You partner can fall asleep instantly and sleep through the night, her body often twisted into painful-looking contortions. You, on the other hand, dread the nighttime. Once a runner, you now suffer from chronic discomfort in any position. You lie in bed miserably for hours, staring at the ceiling with your knees throbbing, stiffness in your back and neck. Your brain goes and goes, and on some nights you force yourself to stay up until three or four in the morning, until you’re completely exhausted and certain sleep will come quickly. It’s always been like this. When you were young, you would squeeze your eyes shut tight and think of heaven, trying to fathom the concept of eternity. Forever. Even then, it sounded like a commitment. Your mother reminded you it wouldn’t feel like forever, that you’d be so happy in heaven you wouldn’t even notice, but still, it terrified you. Forever. Even as a child, there were times you wished you weren’t locked into the promise, times you thought you might rather just reach old age and disappear.

8

The winter before the wedding, you and your partner bring your parents together for the first time at a restaurant outside Houghton Lake in Michigan. During dinner, your partner’s mother mentions the wedding and asks your mother how proud she must be. Your mother raises an eyebrow. She and your father are Catholic, and while you don’t know the Church’s official stance on nondenominational ordainment, you imagine it’s not something they’re fond of. “Is that right,” your mother says when you elaborate. And it’s the last you speak of it to each other, even after the wedding pictures pop up on Facebook, when she reminds you she’s watching with a conspicuous “Like.”

9

Ask yourself what you know of love. Filter this, like everything else, through your obsession with sports. Think of the quote by former major-league pitcher Jim Bouton: “When I first came up, I thought major-league pitchers had pinpoint control, and I was worried that the best I could do was hit an area about a foot square. Then I found out that’s what everybody meant by pinpoint control, and that I had it.” Because you suffer so deeply from imposter syndrome, you apply this quote gymnastically to all facets of your life. For you, love develops like this: first, impossible, because it isn’t so loud or obvious as you are led to believe it will be, because you are not so excitable as lovers are supposed to be, because you steel yourself against it and are gradually worn down. You push love away until it’s impossible to deny you’re immersed in it wholly. You reject your own love story until you can’t, and even then, you are always looking for reason to doubt. Surely others have loved deeper, more meaningfully, more easily. Write this down and scratch it out. You can’t start here, you can’t admit this to anyone, for fear they’ll doubt your love is real.

10

Your summer-long separation began the night of your college graduation in Michigan, hours before you were to board a plane for East Asia, leaving your partner alone and broken without the shock of a trip to distract her. You made the decision weeks earlier, at the worst moment of your breakdown, when you were most sure your move south was a move you needed to make alone. When you came back from your trip, everything about you was unstable and disjointed. You regretted the separation, then regretted your regret. That summer, you and your partner were separated by a hundred miles, two hours on the interstate between your parents’ respective homes. By the time you made up your mind, she’d already given up on you, preparing to move south for a teaching job not forty miles from the university you’d be attending. When you moved down a week after her, it felt like you were chasing her. Your father stayed two days to help you settle, and the minute he left, you were driving east across a still-foreign state to see her. You nearly gave up when you saw how cold she’d grown toward you, how you’d forced her into a version of herself you hardly recognized. The healing happened slowly, with week after week of hour-long drives, nights alone in her guest bedroom, patience and tears. The most frightening moments were when you thought it all might be hopeless, when you feared that the mistakes of your past were permanent and irreparable. Forever. When your summer-long separation ended, when you regained your partner’s trust, neither of you knew how to talk about it with others. Her co-workers asked you if you moved down together, and to make things easier, you just said yes.

11

Start writing the ceremony only when there’s no time left to procrastinate. First, create a basic outline. Processional, greetings, speech. Vows, rings, pronouncement of marriage. Kiss, closing remarks, recessional with music. List headers on a blank document until everything is in place but your speech. Try to ignore your fear that you’ll bungle the ring exchange or forget to instruct the newlyweds to kiss. These fears are not irrational, but their consequences are minor. Obsess anyway. Take this obsession, your fixation on self-perfection, your acute sense of guilt, your terrible fear of judgment and commitment, and try to blame it all on religion. You know it’s not that simple, but you rationalize anyway, holding onto religion long after you swear you’ve left it behind, using it as a crutch you only realize you’re leaning on seconds before you crash to the ground.

12

Skype with the couple a month before the wedding. Discover their origin story: he, a guitar player and she, a singer in a rival band. They are both your partner’s age, a year older than you. She works as registered nurse while he waits tables and works toward his college degree. She and your partner were college roommates, and the four of you occasionally went to see live music at downtown Saginaw’s Hamilton Street Bar. Though the couple has always seemed so perfect, you discover they are more like you and your partner than you thought. He, like you, had moments of doubt, poor and hesitant to commit. She, like your partner, was always a step ahead, financially stable and ready to settle. Ask the couple when they knew they’d found the one and try not to be surprised when they both say it happened in the first three months. When you ask them to respond to your generation’s often skeptical views on marriage, don’t let it slip that you are, or at least you’ve been, one of the skeptics. They tell you that even though they both grew up in families torn by divorce, they see marriage as a way to evolve. They define marriage as one person saying to another, “Yes, I’m going to give you everything,” and though you want to be skeptical of such a reduction, their energy almost makes you believe.

13

Three days before the wedding, take a Greyhound bus from Columbia, South Carolina to Detroit. Your partner drove up a week before you, and she makes the three-hour trip south from Cadillac to meet you at the station. For this, treat her to dinner at your favorite place in the city, a Thai restaurant in a converted Eastern Market firehouse. Stay the night in the suburbs with your sister, the married mother of two children. A woman who, six months later, will laugh as you fit a collar on your dog, whispering loudly to your partner that for you, dog ownership is “good training.” The next morning, drive the hour-and-a-half north to Saginaw, the city where you went to college and the city of the wedding. Have lunch with one former professor and tea with another. Arrive late to the rehearsal with your partner only to find you are still the first ones there, that the couple won’t arrive for another twenty minutes. As you lead an informal rehearsal, try not to feel like an outsider around a bridal party of close friends. Ignore the eyes of doubtful parents evaluating your age. At dinner, the couple gives you a gift bag—a six-pack of your favorite beer and a glass embossed with your initials. Accept their gratitude for something you’ve yet to do. Try to be convinced when they tell you they’re sure you’ll be great.

14

People have described you as “muted,” and it’s true you’ve repressed emotion your entire life. There is no origin story for this, though you hear it defined as a distinctly Catholic trait, even distinctly Midwestern. You repress pain, longing, happiness, and especially love. You’d like to think of yourself as measured, but you keep even yourself at such a distance, you often find that you’re embarrassingly oblivious to the workings of your own mind. This is ultimately what’s responsible for your summer-long separation: a gap between what you thought you wanted and the truth you pushed away, deep into your own recesses. This is why your words sometimes feel hollow—they are fragile things that mask your confusion. Occasionally, though, these fragile things shatter and let loose a flood of repressed emotion, a startling and overwhelming sense of clarity that makes you feel whole. This happens repeatedly over the course of your trip, triggered by something so simple as a hug from your sister or a kind word from your professor: a humbling epiphany of the ways you love and are loved, a realization that though you often know little of what you feel, you have been feeling it for a long time, terrified of letting anyone know.

15

Stay relaxed the morning of the wedding. Check into the historic Montague Inn on the Saginaw River, then drive back across the river to campus for a haircut and lunch. Your partner is a bridesmaid, so she’s otherwise occupied when you come back to wander the grounds of the inn, review your script, sip water and scan the library for titles you recognize. Decline the groomsmen’s invitation to down tall boys in the carriage house, but silently approve of the level of drunkenness they’ve achieved by mid-afternoon. Greet your partner’s friend and your partner’s parents in the courtyard for cocktail hour. When your partner’s father drinks too much too quickly and quips that he’ll only pay for a wedding if it happens in the next two years, just laugh with him. Smile. Drink slowly. When the groom-to-be asks if you’re ready, ask him the same, and watch his grin stretch as wide as you imagine yours to be.

16

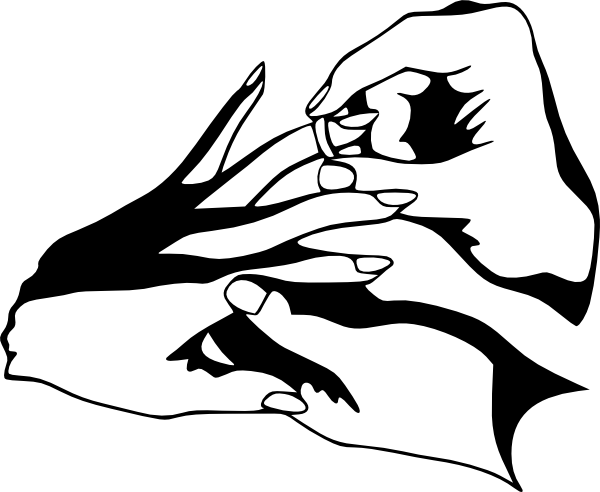

Stand at the end of a tree-lined gravel path with your back to the river, facing an arrangement of fifty chairs and a small standing crowd. When the bride walks down the aisle, instruct the crowd to stand. When she and the groom face each other, both weeping, welcome the crowd and thank them on the couple’s behalf. Talk about how the couple met, how they’ve stayed together over the years. Talk about cynicism and love. Say that if there is a couple that might restore lost faith in marriage, it’s this one. Mean everything you say. Be vulnerable with people you’ve never met. Say this: “The more we interrogate love, the more we poke at it and prod at it, look at it from different angles, the more we begin to understand about ourselves and our partners.” Wonder if this is more for the crowd, the couple, or yourself. Cite Ambrose Bierce’s cynical definition of love—A temporary insanity curable by marriage—and refute it with better definitions. Quote Frost, Rilke, Rumi. Quote Baldwin: “Love does not begin and end the way we seem to think it does. Love is a growing up.” Pass the microphone for vows. Handle the rings cleanly and ask the couple if they take each other, lawfully, forever. By the powers vested in you by the World Wide Web, pronounce them husband and wife. Send them away to applause, realizing only when they’re halfway down the aisle that the crowd has been standing since the procession of the bride because you never instructed them to sit.

17

The was nothing about your summer-long separation that wasn’t your fault. If there’s a sign of your personal growth in the past two years, it’s visible only in perspective: you are more clear to you now. You know now that you took your own anger and fear out on your partner, convincing yourself she was the reason for your unhappiness, that her absence would solve you. The night before you left for East Asia, you told her you never missed her when you were apart, as if that was any explanation, as if you weren’t about to spend the next three weeks trying to convince yourself it was true. You made mistakes. You are at fault, but not forever. The most challenging thing you’ll ever do is not to beg her for forgiveness, but to forgive yourself. Learn that there’s inherent judgment in forgiveness. Learn that when your partner says she forgives you, she’s seeing something in you that you can’t see.

18

Take a deep breath and walk back to the reception tent alone. You receive a handful of compliments, but mostly, people are ready to drink. The wedding is young, Gatsby-themed, and it’s a smooth transition from ceremony officiant to another partier on the dance floor sucking down 7-and-7s. The bouquet toss is rigged in your partner’s favor, but you are easily boxed out for the garter. Note the surrealism of hearing Ginuwine drift over from the dance floor to the deep backyard of the historic inn, echoing off the moonlit river. Get drunk enough to forget about signing the marriage certificate until the end of the night. When it’s time, steady yourself on the table and squint one eye to make sure your signature stays on the line. Drunkenly appraise the night with equal parts satisfaction and relief. Be glad that you followed through.

19

Your partner briefly dated another man during your summer-long separation, and later you learn that he was at the wedding, that he saw the two of you in the drink line, and when you turned to order your drinks, he told your partner she broke his heart by going back to you. Later, you learn he was the couple’s first choice to officiate the ceremony, until he fell out of their favor by sleeping with a married woman, a friend of theirs. Though you were right to assume you were a replacement, consider that your selection wasn’t necessarily a sign of desperation. Consider that their choosing you may have been a purposeful sign of faith, redemptive in its own right. Try to suspend your judgments, but do allow yourself to indulge in the clichéd belief that perhaps you were the better man—if not better than him, then at least better than the man you were before.

20

The next afternoon, you and your partner get in her car and begin the thirteen-hour drive home to South Carolina. You came up separately but you’re going home together. This feels so symbolic and revisionary and perfect that even getting stuck for hours on I-75 isn’t enough to sour the mood. During that time, your partner raves about how well you did at the wedding, how glad she is that the couple asked you. For once, accept her compliment and her joy. If she is blinded by love, as you too often allow yourself to think, that blindness may offer more truth than the censure of your harshest critic. Smile, close your eyes. Trust her to guide the both of you home.