How do you starve a hillbilly to death?

The dawn sun is bright and the air is cold. It’s November and the C&O squealing across the tracks sounds the way Carter feels, brittle and stiff, bending to the weight and trying hard to stay true. But in this weather, in this light, there are prayers that are groans.

The backyard is chicken-pecked down to mounded dirt, hard and slick as shale. He focuses on how the packed dirt stretches the entire length of the yard, ending at the railroad tracks. When Brittany first suggested they move to her aunt’s old double-wide less than two years ago, the property was manicured. Her uncle went so far as to lay plots of zoysia grass, the kind used on golf courses that ends up looking more like turf than actual grass. Walking on it was like walking on carpet. All that was gone, now. Quick summary: attempted poultry yarding, add rooster, aggression. Now it’s all food stamp cards and bill extensions and unemployment, but only if he can keep proving availability to work and doesn’t turn down suitable job offers. Later today they’ll all drive the hour and a half into Wise for cheese and whatever else they’d give. That’s something the government never expected, people crossing state lines for the handouts. Right now it feels like both a small victory and an embarrassing mess of a thing all at the same time.

Poor as a snake. Can’t afford to pay attention. Broke as a joke. Living on cheese, looking like death on a cracker. The Army wouldn’t have you. So hungry his backbone’s chewing on his hind end thinking it’s a piece of meat. I’d eat the southend of a northbound mule. Hillbilly, redneck, reject, ingrate, banjo-playing squeal like a pig no escape. He who does not work, does not eat. So lazy wouldn’t strike a lick at a snake. Backward. Hick. Dumb as a box of rocks.

At one time, the government was required to purchase dairy products like cheese to keep the commercial companies afloat. The government could then sell or give the cheese away. The cheese stockpile equaled to more than two pounds for each person living in the United States. Commodity cheese is what families called it. And sometimes government cheese. Reports will say that government cheese, which was artificially colored orange, was frequently moldy, but you won’t hear many of those reports from the hillbillies who enjoyed it. Those who received the cheese did not lose any food stamps and were not required to trade their stamps for the cheese. It was provided to welfare and food stamp recipients, as well as people drawing government checks, at no cost to them.

Kids standing in the cheese lines in plazas and shopping centers rarely, if ever, understood they were in the midst of a welfare program. For them it was a festival, or at least that’s what most kids would have told anyone who asked. What were they standing in line for? Grilled cheese sandwiches, they might say. Not to mention a road trip. Back then there was less for kids to do for fun; a trip out in the car, if only to drive around, was an event.

At that time, in that place, the cheese came in a cardboard box with a removable and replaceable lid. Inside, the block of cheese itself was sealed tight in plastic. It was normally cut in thick slices and the kids were always given the first few pieces on the ride back home. You’d have thought it was peppermint candy the way they put it away. There were other items, too. Beans, for instance. Flour. But nothing was as celebrated as the cheese.

A typical evening after a cheese run would be the family eating, from both the cheese received that day and other food traded for with stamps. Once everyone was full on monthly treats like black forest brownies, Red Baron pizza, Tang, and donuts, among other nonessentials, the entire family gathered in the living room. Here, with a box fan in the window if late spring or summer, especially if it was raining, everyone would get ready for movies.

In the early days of the VCR, the family would go to one of several local video stores and rent one for the weekend along with up to ten movies. This meant from Friday night to Sunday by six in the evening there would be ten movies watched – Predator, Dirty Dancing, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Top Gun, National Lampoon’s Vacation – all in a weekend, which meant late nights without a set bedtime. And, since the stamps had just come in, there was plenty of that to go around, chips, pop, Pillsbury oven-baked cinnamon rolls, four different kinds of cereal.

Kentucky makes a claimant verify job searches in different ways. For Carter, that means more than just confirming he’s looking for work in general. They make him give detailed breakdowns on what he’s doing to find a job, which means, basically, giving them at least three companies where he’s applied during the payout period. And they check on this stuff. There’s been calls from Taco Bell, Lowe’s, Wal-Mart, and a little speciality shop called The Men’s Corner that puts price tags on button-up shirts for more than Carter would pay for a rebuilt motor. Looking out on the bald backyard and watching the morning train push coal, the thought of making burritos at Taco Bell is enough to tighten his stomach muscles. If he could throw up he might feel better.

When these places call, he has to follow through. Not only for the unemployment benefits, but because Brittany would lose even more respect for him than she already has. And eventually she’d turn the kids against him in the same way. Two kids, a boy and a girl, growing fast. What he’d really like her to imagine is him serving steak chalupas to her and her nurse friends one Saturday during lunch hour. In the really bad arguments lately he’s offered up this very scenario but she only says it’d be better than admitting to her coworkers her husband doesn’t have a job. It’s doubtful even she believes that.

Breadwinner. If a man can work, he ought to work. That woman is independent as a hog on ice. Going under the mountain. Coal tattoos. Working the belt. Soup beans and taters, ponebread, greens, half-runners. Wore down to the nub. Day jobs. Scabbing. Crossing the picket lines. But you can’t squeeze blood out of turnip. It don’t amount to a hill of beans. At boy moves slower than molasses. Lollygagger. About as useless as teats on a boar hog. Still a day late and a dollar short. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. Moocher. Not a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out. Ornery as all get out.

The good news is that everybody gets a little break from all this today. It’s Carter’s birthday and nobody wants to keep putting him through the wringer on his birthday, not even Brittany. When asked what he wanted, Carter was responsible and said they couldn’t afford a gift, waited a beat, and finished by saying it’d be really nice if he could get a day off from her parents. They had been to the trailer nearly every day since he worked his last day on the crusher at the Tram prep plant. She wasn’t thrilled (her dad had been trying to finish on a few projects on the place and that meant begging him off) but it was only for today. And now today is here and he’s forty-five, buying a little me-time on the back porch, and without any prospects. If he was a horse, they’d shoot him.

Before Brittany gets back from the store, he walks across the yard to the tracks. The overloaded coal gons have left the hollow, on the way to Robinson Creek, but the rails are still warm from the run. If he grips them just right, palm pushed down, he can feel the vibrations ringing. It’s nice how it lingers that way, but it’s tough, too, knowing he might have been the one who worked that coal at one time. Across the way, where the track ballast ends and the regular flattening of the earth starts again, somebody planted a row of birch trees years ago. They’ll be gone soon. Birch trees die young. And then there’ll be nothing to stop his backyard from flowing through and over everything else.

Ronald Reagan signed and authorized into law that five hundred and sixty million pounds of cheese that the Commodity Credit Corporation had ended up stockpiling should be distributed free to the needy. The bill said that any state asking for the cheese would get thirty million pounds in five-pound blocks. One government representative was quoted as saying that probably the cheapest and most practical thing would be to dump it in the ocean.

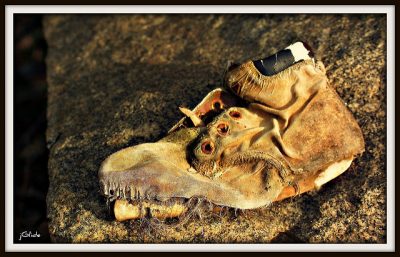

How do you starve a hillbilly to death? You hide his welfare check in his work boots, that’s how.