The instant coffee went down like fracking fluid. Sour. Smelled like miners’ socks. Clam chowder, microwaved, and turkey jerky of unknown vintages had been scrounged. Untouched by either of them.

So the duo departed the house. Confronted the dreary morning in silence to try to find the car.

Will, the son, drove the two of them in his turd brown decade old Cutlass with the Waldo Community College parking sticker. They peered through the windshield tinted with bug guts.

“You know where we’re going?” Will’s father asked.

“The arrest report said Route 256. Mile sixteen. Should find it parked off to the side. The wrong side.”

“You saw the arrest report?”

“The officer at the police station handed it to me last night. This morning, guess it was.”

“I must have been sleep-walking,” the old man said.

“Walking didn’t help your case. But you were awake.”

Will turned his head to look at his father who did not meet his eyes. His father instead stretched over and snapped off the radio. It had been thumping an old ZZ Top shuffle. Heavy on the low end. Will popped in his ear buds then jacked the radio back on.

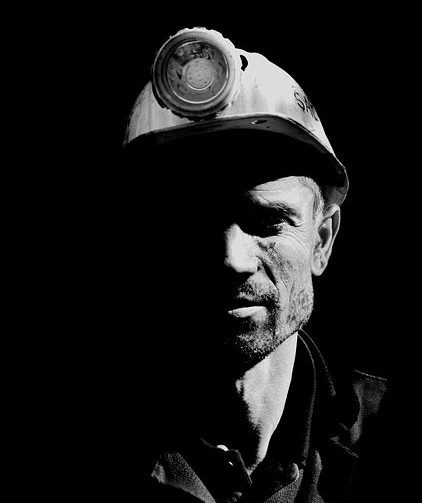

The mining equipment company that the father worked for had a genetic repulsion to regulatory oversight and a talent for union busting. A reckless drinking culture. He was in financial management. Hopscotched his family all over the country as he clawed his way up the rungs with pickled stumps. Eight houses and five states before Will’s sixteen birthday. Three time zones. Will’s doctor offered a theory that his ulcer and bizarre case of teenage shingles could have been born of stress such as that. “Nah,” Will had told him. “It’s all a welcome distraction.”

It was March and damp cold. They drove without speaking for several miles through the bleak Ohio countryside. The sky looked like worn sandpaper. Oak and maple leaves had not yet popped free of their tender buds. Will was on spring break from the community college he matriculated through a process of elimination. He calculated that it was not an opportune morning to trot out his journalism aspirations. Accounting was the only major the old man felt would lead to a job. Ally, his older sister by three years, was in Nassau with her private university friends.

“How did you know to come for me earlier?” the father asked. He rubbed his temples. Shoved his fingers through his graying hair. His eyes looked like TV dinner tomatoes. Stewed, with that soggy something on top. His skin like the adjacent puffed raspberry turnover. He realized that Will did not hear him over the bass pounding in his ears. He reached over and tapped him. Will yanked out his ear buds.

“How did you know to come for me?” the old man asked, still a bit lit.

“I was sleeping. The phone rang.”

“What time was that?”

“Like 2:30 this morning. Phone was ringing in your bedroom. Ran to answer it. Wondered why you weren’t getting it.”

“Why didn’t your mother answer it?”

Will looked at him.

“You know she’s not home, right? She’s with Aunt Dot in Harrisburg. Remember?”

The old man said nothing. He and his wife screamed often about his excessive boozing. Like a vinyl record skip that wouldn’t quit. Her prohibition efforts were amped after his inaugural drunk driving arrest in California. As it turned out the freeway exit did not double as an onramp. She was left to drive the car solo through East LA at three in the morning. To get home to her panicked children. After being sprung the next morning, his reflex was to up the concealment game. Hide the extent of his imbibing through enhanced creativity.

Pastures congested with languid cows passed on both sides of the car.

“Who was on the other end of the phone?” the father resumed.

“I don’t know. Can’t remember. Officer Starch Collar.”

“What did he say to you?”

“He asked my relation to you. If I was an adult. If I had a driver’s license.”

“Then what?”

“He said I could come to get you at 5:00 AM. I asked him if I really had to.”

Will glanced at his father. It had flown over his head.

“Well, he was an asshole. A pussy,” the old man spat. “A real dick.”

“He sounds conflicted.”

“Claimed I was in the wrong lane. On a two-lane road.”

“A fifty-fifty shot?”

“Treated me like some kind of drunk.”

“Pretty sure you were drunk. The arrest citation said you blew a 0.2 percent.”

“Bullshit. I don’t remember even doing a test.”

They came upon an odd and macabre roadkill aftermath. A flattened mashup of both fur and feathers. A large red-tailed hawk had its claws still plunged into a small rabbit. The hawk, it seemed, had been willing to stare down a speeding car before it would surrender its prey. Tenderized by a week of maggot gorging and radial tires, the tragic duo’s stench consumed the free oxygen in the car.

“Hey, the arrest report mentioned a passenger,” Will said. “A woman. Said she was not in any condition to drive your car. So another officer came and took her home.”

The old man stared straight ahead.

“Just a lady from the office. Her car wouldn’t start. After our employee meeting. I offered her a ride home.”

Will’s mother had presented Ally and him with letters she found in the old man’s briefcase a month earlier. The letters were scrawled by a woman with the same name as in the arrest report. In these missives, this woman told the old man what an amazing lover he was. Despite his bulging disc and COPD and all. She was not a stranded employee of his father’s company. She served drinks at the Skis and Grub sports bar. Had a Yosemite Sam tattoo below her turquoise pierced bellybutton. Will’s mother was Queen of the Nurses’ Ball. Got Will and Ally to music lessons, to church. At least at Christmas.

The son spotted the car first. Pointed south on the northbound side of Route 256.

Back at home, Will’s father was embedded in his worn leather reclining chair. As though in a womb. Pewter cigarette smoke ascended above the top of the newspaper that veiled him. Will was perched on the edge of the sofa like a lone pigeon.

The teen cleared his throat to speak. Short of utterance, he snapped off the words. Words he had rehearsed. His eyes were tricked to his own reflection in the fireplace glass. His Uncle Ted opined once that he had an odd shaped head. A haircut like Ish Kabibble.

His sprawled form, expanding at disproportionate rates, peered back at him. His legs were growing faster than his arms, his trunk less so than his neck. Beard barely sprouting at all. All destined to sync-up at some point. Some point soon, he prayed.

The old man unfurled a serpent of spent smoke over the top of the newspaper. His face was a city map. Red streets and a myriad of blue alleys. He molded his fingers around a can of Diet Coke and raised it. His lips anticipated the arrival of the can as if for a deep kiss. The contents of the can were never depleted in full, topped off by some hidden fountain eternal.

At the opposite end of the room from the father’s chair resided a new wet bar. Behind the bar, standing at rigid attention, like well-drilled soldiers, was a diverse selection of bottles. The bottles were depleted to random levels with liquids both clear and amber.

“This is only for company,” the old man assured. “So we don’t look like down-homers.”

Prior to the bar being installed, the father, with his can of Diet Coke in tow, took mysterious trips to the garage. These sorties to the garage would last but a few minutes and would pass without comment. Eventually without detection.

Will cracked this curious puzzle on a recent and frigid winter day. A day when the wind scolded from the north and the snow pummeled in a furious tantrum. In the garage, Will probed deep into yawning bowels of the snow thrower chute to ensure that nothing was obstructing it. His fingers were greeted by a sensation both cold and sleek. He extracted a bottle of cheap gin. Its clear contents neared exhaustion. As if returning a baby bird to its nest, Will placed the bottle back into the snow chute. Will swatted the spider webs off of the rusty hand shovel and attacked the snow like a possessed city plow.

Collapsing his newspaper fortress, the father shattered a torpid silence that had consumed the space between them.

“Where do you suppose the dog is?” he blurted.

“Not sure.”

“Been a long time since I’ve seen her,” his father continued. “You should go look for her. Maybe she’s shut in a closet or something.”

Will looked at his father with a honed flatness.

Their dachshund, gray faced and plump, then ambled into the room. Her tail shot off at a curious angle, halfway down, from a heedless rocking chair incident. She craned her neck to consider the rising cigarette smoke. Wheezing in short labored pants, she twirled around twice and flopped.

The father snapped the newspaper back in front of his face.

Several moments passed. The father then thrust forward in his chair. He trained his crimson eyes on Will.

“Don’t you have a geology report you wanted to show me? Something about coal? Bituminous coal, or something?” the old man asked.

Will permitted the urgency in his father’s voice to marinate. He glanced over at the wet bar. Then he met the old man’s eyes square on.

“That was like two quarters ago, Dad. Now I’m not sure where it is.”

“Well. I want to see it. Can’t you go find it?”

“Now? It’s probably upstairs in my room somewhere.”

The old man leaned forward again.

“I want to see the report. Now,” he said.

“I’ll go upstairs. See if I can find it,” Will said.

“That would be good, Will. Good idea. I want to see it.”

Will rose from the sofa then hesitated. He turned toward his father who was again veiled by the newspaper.

“What I was going to say, you know, earlier, was that I thought you might want some company,” Will said. “After this morning. I’m, you know, here if you do.”

The pages trembled in his father’s hands. No response from behind the newspaper.

Will entered his room upstairs. On his desk he pushed around stacks of old yearbooks, comics, fishing magazines and school papers. A creative writing assignment from freshman English admonished in red: Watch those adverbs! Lazy writing!

“Screw the effing adverbs,” he mumbled. “Slowly.”

Near the bottom of the stack, Will unearthed the bituminous coal report. He held it to his mouth and blew off some dust. He imagined for a moment his father savoring the B+ in large script at the top. Not bad. Fuck no. Not bad at all.

Will made his way back downstairs to the hallway leading to the family room, with some pep in his step. His stocking feet fell silent upon the wood floors. Faint bottle clinking sounds seeped from the family room. He froze and leaned in close to the wall, his cheek tight against it. His line of sight was straight back to the wet bar. In seconds he observed his father slither from behind the bar. Will studied him as he glided back to his recliner, specter-like. As if his feet were not touching the floor. His soda can like an amulet in his hand. Salty tears fractured Will’s vision. Seared his eyes like white fire.

Instead of continuing to the family room, Will entered the kitchen. The arrest papers were still on the counter, next to the reeking filmed over clam chowder. He thumbed the edges of the papers then lifted the entire arrest report from the counter. He looked again at the B+ coal report in his other hand. He dropped it on the counter. The arrest report landed on top of it.

Will slipped into the bathroom upstairs and closed the door. He slid open a small vanity drawer and reached to the back, past the rolled toothpaste tubes, old lip balms and cotton swabs that had long ago escaped their box. He extracted a tin marked for water-proof bandages. With his thumb he released the lid. The tin housed a blue disposable lighter and a few examples of how not to pack rolling papers. Selecting one, he straightened it out from a slight crimp. Lifting it to his nose he sniffed it like a wine cork. He flipped on the ceiling exhaust fan and lit up.

Stretching his neck, he positioned his mouth as close to the fan as he could. He emptied his lungs straight into the vent, like an eviction of his soul entire. Sucked away without a trace.