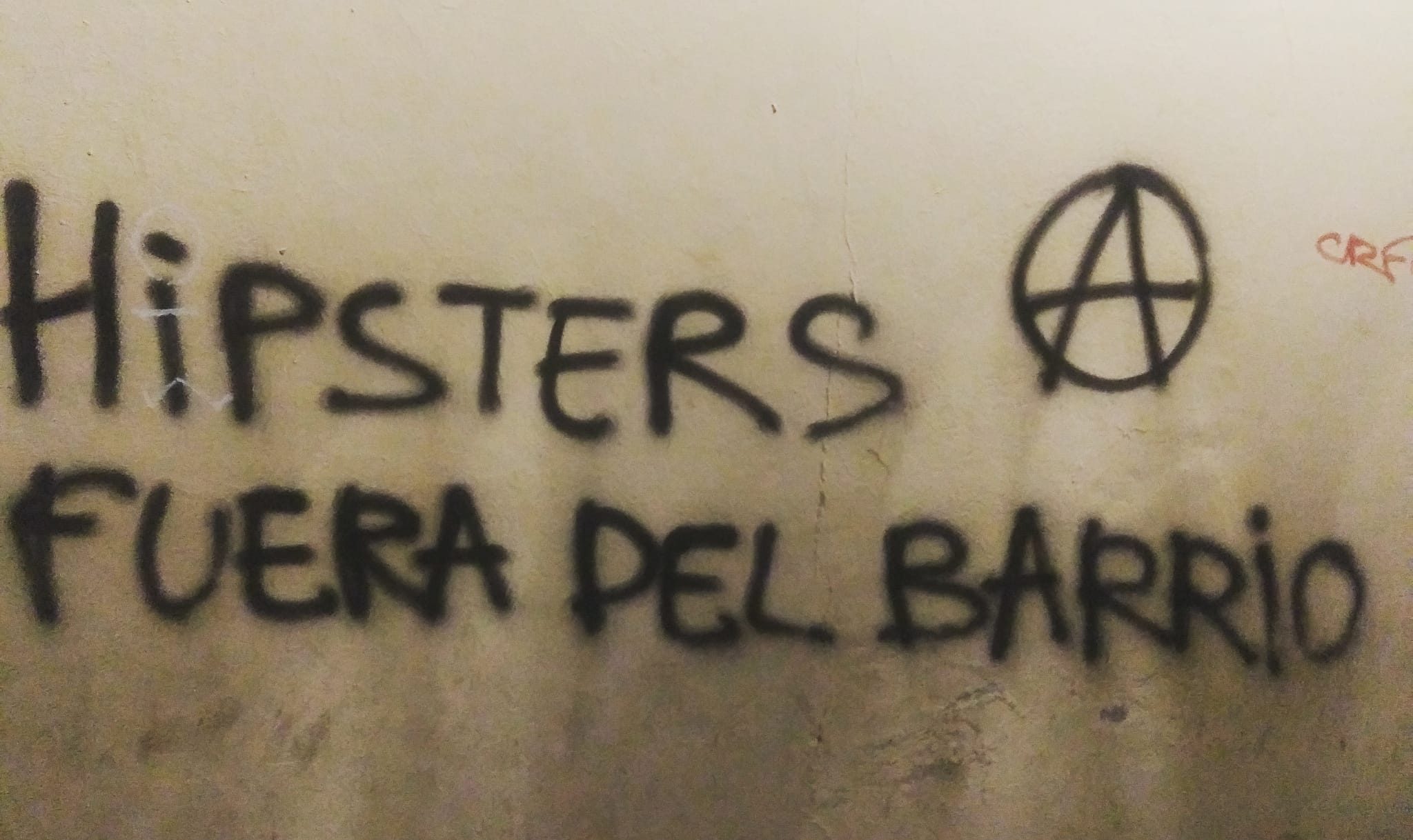

guiri (spanish): a foreigner, a tourist, usually a white person

When I was nineteen years old and had smoked a little too much pot, I became the first person in my family ever to go to therapy. Somewhere in my brain, down below layers of pinkish neural tissue and grey matter, I’d become fuzzily convinced that any suffering that took place in the world that I did not actively prevent, I was partly responsible for. As there is an overwhelming amount of suffering just in America let alone The World, and as I, at age 19, possessed no particular skill-set that would help greatly in the alleviation of anyone’s suffering, including my own, this conviction of mine led to a sort of total paralysis that quickly caught up with me, as all neuroses inevitably do. The therapist after a long slow while, and to his credit, got my head screwed back on straight, and I eventually managed to more or less resume normal function, with the tools to hold this peculiar, morally grandiose form of narcissism in periodic abeyance. I stopped smoking pot, took up jogging. Voila.

Stuck indoors for six weeks, subject to Europe’s strictest (or at least second-strictest) lockdown I have had the unique experience of watching a bunch of otherwise well-adjusted friends and family flit in and out of states that were, at the very least, adjacent to that of my 19-year-old self. Here in Spain we spent 6 weeks isolating in our homes. I do not mean this in the gauzy sense of New York tech-company VC’s isolating in 8-person Airbnbs in Vermont. (A Spanish friend remarked to me recently in English “They should not get to use our word. They should have to use a different word [than isolating].”)

People here were not permitted outside for any reasons other than grocery shopping or to seek treatment at a hospital. Not long after the initial lockdown, additional restrictions went into place forbidding people from going up on their roofs to take in the fresh air. There were a handful of instances, circulated online and in the national papers, of Spanish citizens calling the police on their neighbors for sunbathing, but for the most part the roof restrictions represented the de jure senselessness of Spanish policy-makers, a rule citizens would vacillate between using as a cudgel against neighbors they disliked, and themselves violating in moments of indulgence, without ever actually getting the police involved. Still, it was long and confused and spiritually cramped period.

For six weeks here, everyone stayed inside and, in order to keep from eating paint chips, all rearranged the kitchen cabinets, played online chess, tried out phone sex, checked up on the government. We keep being told that we are “living through a trauma” which as far as I can tell, is a way of saddling us each with a moral responsibility to derive meaning from what is an inherently meaningless experience. Trauma does not naturally confer great wisdom on those it touches, but sometimes it can at least help explain your situation to you. Our situation, economic, governmental, personal, moral, has been explained to us in stark and unadorned terms. It is, it turns out, not great.

I personally, in order to stave off psychosis, became increasingly obsessed during this time with tracking down a particular audio version of the book War & Peace. After listening to Part 1 online and investing psychologically in discerning the specific voice actor who had produced it, whoever he was, I became, in short order what you might call “unhealthily fixated.”

The problem, I discovered, was that parts 2 and 3 and 4 and so on, of the audiobook, as performed by this certain anonymous voice actor, were nowhere to be found—the account that’d originally posted Part 1 online did not have any of the subsequent sound files. After scrolling the comments, searching around, posting in several different forum threads, I discovered that the voice actor’s name was Alexander Scourby.

Scourby was a golden age Hollywood and Theater Actor. He had small roles in Giant alongside James Dean, as well as Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat. He played Claudius in a critically acclaimed production of Hamlet and the title role in Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo.

But Scourby’s most famous work by far was as a voice actor. He has a sonorous type of gravel about his reading-style, that imparts a precious intensity to the passages he recites. He is famous—at least in the subculture of people who care deeply about audiobook actors—for having done enormous amounts of research and preparation before he embarked upon any of his voice projects. One of the black and white photos I found in the course of searching for information about him depicts Scourby perched in a studio booth leaned very close to a pop filter with a cigarette burning in between his fingers and a large hardcover propped open in the other hand.

The comments beneath Part 1 of his free War & Peace reading online are inexplicably passionate for having come from a bunch of people listening to a 50-year-old recording of a nineteenth century Russian Novel. One commenter thanks the original poster for “<<A beautiful reading…!!!” One among several more asks, “Where is the rest of the book read by this narrator??? There is no other version that is tolerable after listening to this version.” Another commenter, who apparently got their hands on the full file, remarks “the audiobook is a masterpiece within the masterpiece”.

These plaudits are made all the more incredible by the fact that Scourby rarely performs the typical trick of dramatically modulating his voice (i.e. making it high and lilty for feminine characters, feeble and shakey for the elderly etc.) so typical to modern audiobooks. He is rather like the Voice Acting equivalent of Cormac McCarthy, who eschews grammatic ornament and punctuation, with the confidence that, if he is doing his job correctly, you will know who is talking and why.

Despite all this, or perhaps because of it, Scourby’s characterizations are sharp and full of uncanny verve. Prince Andrew, in his reading, is full of brash confidence, quiet and arrogant intelligence for which he pays dearly. Scourby’s Pierre absentbminded and ponderous but capable of great flashes of passion and impetuosity. Andrew’s sister Mary is imbued with heartbreaking intelligence and a sort of rich empathy which Scourby manages uncannily to convey to you, the listener, in between other character’s mercilessly disparaging comments about her physical attractiveness and devout Christianity. (“It would be good” marvels Scourby-as-Andrew at one point, “It would be good if everything were as clear and simple as it seems to Princess Mary. How good it would be to know where to seek help in this life, and what to expect after it…) The performance stands as a monument, but like one of those old movie sets constructed out in the desert, one covered over by a continental vastness or buried beneath unadulterated caprices of the age.

Scourby is extolled by some as “the greatest voice actor of all time” or, at the very least, of his generation. He is also one of the few actors to have recorded an audio version of all 66 books of the King James Bible (which, one forum poster remarked, “I consider as The Version”). Scourby himself apparently bristled at this reputation when he was alive, remarking once in an interview “’Oh, I suppose they mean it as a compliment. But what actor wants to be known as a voice?”

I do recognize how unaccountably strange it is to have become so deeply fixated on this man and this audiobook. But for six weeks now, we have been stuck inside and told, by government and health officials, that each trip we take to the grocery story, to walk our dogs, or pick up medications, or get our hair cut, will have a direct irrevocable impact on the spread of an invisible infection and the deaths of our neighbors. In the mean-time we stare at charts that represent, in the abstract, civilizational mass death and economic collapse. It seems, to me at least, that among all the other projects this pandemic has laid bare, we will also need to set to work redefining what constitutes strange or ill-adjusted thinking.

Even after learning Scourby’s name, it was unbelievably difficult to try and locate the audiobook anywhere. Audible, which is owned by Amazon, has a few recordings by Scourby, but not his War & Peace. Librivox has free public-domain recordings that sound as if they are being recited by an actor at gunpoint, but zero from the acclaimed veteran. Other websites have sound files that claim to be the Scourby version but end up, upon download, being (perfectly adequate) readings by Frederick Davidson or Walter Zimmerman. I reached out to friends who regularly haunt weird corners of the internet, explaining this strange mission I’d embarked on in isolation. I couldn’t adequately articulate why precisely it was important to me to find this one specific recording of War & Peace, by the man who’d done “The Version” of the King James Bible. I could not, and still cannot, explain why I became interested in this person who, even to modern listeners somehow manages to serve as capable stand-in for the voice of God. I just know that I had searched and read and found very little, until a friend of mine one day sent me a URL to a Canadian government site.

The link my friend had sent was to the webpage of the NNELS. The Canadian National Network for Equitable Library Service. This, it turned out, was why the audiobook was so scarce. Scourby’s recording had been made specifically for the blind.

Once I learned this, I searched his name again, along with this new, more specific criterion. I came across a comment buried below a YouTube video,“Scourby was a legendary narrator but the hundreds of his recordings were done for devices made solely for the blind. I’m not sure how this one escaped and who digitized it.”

It turns out, over the course of his career, the actor who so hated being known for his voice, worked in partnership with the American Foundation for the Blind, to make 422 such recordings, of classics ranging from The Iliad to Faulkner’s The Sound And The Fury. In his obituary in 1985 the New York Times described him as being responsible for “Hundreds of master works.”

The NNELS possesses a digital copy of the file, and I rather stupidly sent them an email, explaining how much I liked the recording, how I had been searching high and low for it. They emailed back, politely apologetic, that since I was neither Canadian, nor visually handicapped, and did not possess a library card, it would be a licensing violation for them to send over the audiobook. I thanked them for their reply and imagined that to be the end of it.

Until, a friend one day sent me a file asking whether the voice on it belonged to Alexander Scourby. I listened and replied that it did. After a fashion he sent along the entirety of War & Peace as read by (now, to my mind) the greatest audiobook actor of the twentieth century. I go up to my roof most days and illegally sit in the sun and listen to Scourby’s stentorian hussars crying out as they manage a series of embarrassing retreats that we are told later is what victory actually looks like. I listen to Scourby’s voice curl like smoke around Dolokhovs bloodless cruelty. Mary’s avowals of constant faith. I have, after nearly a decade, learned several tricks to staving off intemperate melancholy. Part of it is to routinize small gestures and expressions of joy, and mini-sacrifice, and intimacy toward the people you love. Part of it is to take up jogging. And part, for me, is to recognize those all-too rare persons who seem capable of speaking in god’s voice, in the acuteness of his absence, even as the words were not meant for me in the first place.