guiri (spanish): a foreigner, a tourist, usually a white person

The Spanish Street San Luis de los Franceses—St. Louis of the French Persons—takes as its namesake a church with looming façade, populated by a crowded baroque of bas reliefs, variegate religious iconography, expressionless cherubim and obtruded cornicework. It is, a Spanish friend told me once, “the best kind [of church], a decommissioned church.” San Luis got its commission in the 16th century from the Jesuits, but when those same Jesuits were expelled from Spain in the 1800s by the government, the building was deconsecrated, and custody of it was handed off to the municipal council of Seville. While I am not religious, on account of poor imagination, San Luis rates as one of my favorite buildings in the city, because the front design is so unabashedly, unselfconsciously busy, and because of how pretty it is lit up at night.

If you travel a little ways up the broken street from the front gate of the church you come upon Plaza Pumarejo, one of Seville’s largest and more historical squats. During the Civil War, Pumarejo served as a prison for dissidents. Later it was converted to a hospice, then finally into apartments. In the late 90s, just as the Macarena was beginning to gentrify, the real estate company that owned the building decided they could make more money selling it to a hotel group, and so intentionally allowed Pumarejo to fall into disrepair, in order to force out the (mostly poor) families who lived there. It prompted a tenants rebellion and the families took over the building. They opened up a community center, and an economic kitchen where you could get a hot meal for 1 euro (then 166 pesetas), they put on concerts and book drives, and opened a cinema where they sometimes showed Fellini films. Yet more residents of the neighborhood, artists, artisans, moved in to replace the tenants who’d been driven out. When, in the late aughts, the owners, via the Guardia Civil, tried to have the residents forcibly cleared, the neighborhood rallied to their defense. There were large demonstrations in the public square. People hung up posters and harassed city council members.

The owner of the print shop opposite Pumarejo, a congenial man with a Roman nose who wears a leather jacket even in the summertime explained the episode to me like this: “Around here, we are of the left.” The police eventually let the tenants be. The squatters still intermittently run the economic kitchen and the book drive, though they have of-late stopped showing the Italian films.

If you continue farther north along the street you arrive almost at once at the old Moorish walls, the mammoth yellow archway, that demarcate the northern perimeter of the Macarena neighborhood— inspiration for the Los Del Rio song of the same name. “The Macarena” represented the first ever reggaeton song to hit #1 worldwide. In terms of ubiquity, of pure earwormy power, “Macarena” singlehandedly put reggaeton on the map, cleared the way for everyone from J. Balvin to Bad Bunny. According to local innuendo the song was originally called Magdalena, after an unfaithful woman, but the band at the behest of the record company changed it to make it more palatable for radio. The Spanish expression, for being unfaithful to someone is “Puso los cuernos” to put the horns on them. My romantic partner one day wandered into the teacher’s lounge of her high school, to find her colleagues gossiping that one of the girls, Maria, had “put the horns on Alvaro.”

“Poor Alvaro,” someone said.

“Poor Maria,” my partner said to me.

The Spanish word for a shameless gossip is “chismoso”

The Spanish word for a hotshot, or someone who makes all the decisions is “El que corta el bacalao” or “he that cuts the codfish.”

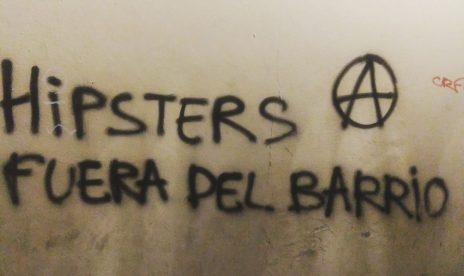

Just to the left of the arch is the Basilica de Macarena. An arresting yellow and white chapel featuring an altarpiece blown out with silver and gold robbed from the peoples of the Americas. The church is the final resting place of Francisco Queipo de Llano, the fascist and torturer who oversaw the execution of as many as 30,000 political dissidents during the course of his professional lifetime, most of them right there against the Moorish wall, which still bears the pockmarks of the firing squads in places. Queipo de Llano’s epitaph identifies him as “an honored brother of the church.” His permanent status there is a bit fraught. Around the neighborhood you can find graffiti that reads “QUEIPO DE LLANO A FUERA.” Demanding that his body be exhumed from its place inside the basilica, removed to some more ignominious location.

If, instead of looking left at the Basilica, you look straight ahead, you’ll see the Parliament of Andalucia, which a Sevillano might tell you is today home to no small number of aspiring fascists itself. Before it housed the Parliament, the resplendent plateresque esplanaded by wrought iron, white cobble, and Spanish elm was the Hospital of the Five Wounds. The name refers to the wounds inflicted on Jesus Christ as he was executed by the Romans. Two in the hands, two in the feet, one in the chest. For nearly two centuries it was the single largest building in Spain, before it got overtaken by one in La Mancha. In the 17th century, when Seville was ravaged by the Great Plague, around 27,000 poor souls entered the building, of those, according to Atlas Obscura, only about 5,000 emerged living, which is to say that the germ had a slightly more merciful record than Queipo de Llano did. Several Spanish politicians have over the years complained that the building is (apparently) deeply haunted. A number of people have given account of a ghost who goes by “Sister Ursula” and who apparently wanders the corridors still looking for patients.

If you reel back down whence you came, and hang any right you please, you will most probably pass the Mercado de Feria, an open-air arcade where sevillanos often while weekend afternoons, weather permitting. If you stay up eating and drinking instead of availing yourself of a weekend siesta that is called a “tardeo.”

Tapas in Seville are not free, like they would be in Granada, or Jaen, or Almeria. I have heard two competing stories for the invention of the tapa (though it is of course possible that neither is true). Explanation # 1 is that, because the summers in Andalucia are so brutally hot, the Crown at some point, decided that it was counterproductive to have Spanish peasants working the fields in the middle of the day. So in the interest of maximizing productivity, the King declared a Siesta between the hours of two and six, so that the workers could go home, have lunch, seek relief from the sun, and return to work refreshed. However, the story goes, not so unlike Raines’ Law years later in the saloons of New York City, the knock-on effects of this new form of societal reordering were not the socially-optimized well-ordered civilization its architect had intended. Rather, giving large groups of predominantly male agricultural laborers off in the middle of the day, assured that no small portion of them would go out and begin drinking. Shortly after the siesta’s creation, Spanish business owners came begging the Crown to repeal it, droves of workers were showing up to work incapacitated, they complained, but loathe to admit error, the Crown penned a second decree to course-correct for the first: Henceforth, for every drink sold by every bartender in the Spanish kingdom, one must also serve some accompanying plate of food. The Spanish bodega owners, duenos and abacerias, began serving small, economical plates of food to their patrons on top of their wine glasses. They were nicknamed “tapas,” lids.

Explanation #2, slightly shorter than the first, also involves the regency, albeit in a less active role. It alleges that the King, during a terrible sandstorm, stopped for a time in a small town in Huelva and, at local recommendation, went to eat at a very famous restaurant there. When he arrived the air was so windy and thick with dust, and the bartender so very nervous, that the man slid a piece of ham on top of the King’s drink, in order to keep the dust out. The King, who had been hungry, was so tickled by the concept he told the bartender that he ought to keep serving food with every drink he brought out, and the bartender, eager to please, started doing exactly that.

The bartender was perhaps correct to be nervous. The Spanish Kings have a historical reputation for varying levels of irascibility, volubility, sociopathy in the national narrative. Don Pedro the Cruel, for instance, was known to force his subordinates to drink the bathwater of his favorite mistress. He also had the Alcalde, the Mayor, hang up a bust of him on a street where he’d murdered a passing nobleman for accidentally shoving him. The street is helpfully called the Street of the Head of Don Pedro. Pedro himself was later stabbed by his brother Enrique for private reasons. If you continue south down the road, you will hit the Metropol Parasol which is the largest wooden structure in the world, and which locals when it was first unveiled pejoratively called “Las Setas” on account of its passing resemblance to a giant mushroom. Now a large portion of the derisiveness has worn off, but everyone still calls it “Las Setas.”

The street just south of Las Setas is Calle Sierpes which, according to legend, is named after a giant serpent that lived in the sewers of the city kidnapping and devouring spare children, until one day the giant animal was killed by an escaping prisoner who’d tunneled out of his jail cell. Killing the snake supposedly earned the man the gratitude of the city, notwithstanding the prison escape, and he was allowed to go forth a free citizen.

The building he escaped from, the Royal Jail, is the same one that once housed an itinerant tax collector named Miguel Cervantes de Saavedra, who spent some brief tenure there as an involuntary guest of the crown. According to competing sources, Cervantes was thrown into jail either for his gambling debts, or for mocking a newly unveiled statue of the King or (this according to Historian Walter Gallichan) “uttering satires upon a lady.” The tour guides enjoy telling visitors that it was in a prison cell here that Cervantes began to work on passages of Don Quixote, widely considered the first novel ever written. The book was a favorite of John Steinbeck, who, later in life, named his camper van ‘Rocinante’ after Don Quixote’s skeletal horse. The sevillanos like to say the book was begun here. The more complicated truth is that, while we know from records that Cervantes began writing the book in jail, it is difficult to pinpoint precisely where, on account of he spent so much of his life in and out of prison in different cities. Still, the story continues to be credulously related, and a dark metal bust of Cervantes stands there, just at the base of Sierpes, where the Royal Prison would have stood. I asked a tour guide once, why he related the story of Cervantes writing Don Quixote in Seville to his tour groups, if he couldn’t be sure it was accurate. “Man,” he shrugged, “he had to write it somewhere.”